It is difficult for anyone watching Annemarie Jacir’s historical film Palestine 36 in 2026 not to discern the many parallels and resonances it bears to the period that followed 7 October 2023. These are not ‘projections,’ a term that suggests contemporary meanings imposed on the past. What emerges here is not a forced analogy, but a convergence of historical patterns that render the present legible through the past.

The film’s very conception belongs to this moment. Whether the project was first conceived before those recent events is not known, but its production, release, and reception are inseparable from them and from the far-reaching global debates they ignited over the conflict with the Israeli occupation.

Debates of context

At the centre of those debates lies the question of context, a question that has shaped much of the discussion, particularly in the West. Did 7 October and its aftermath mark a rupture from the history of the Palestinian cause, or was it an extension of a fraught and intricate trajectory?

Palestine 36 affirms two essential propositions. The first is that the project of seizing Palestine and obstructing the rise of an independent, sovereign Palestinian state is not a recent development—it goes back to British colonial rule in Palestine.

The second is that the forces which opposed Palestinian aspirations for statehood since the Balfour Declaration of 1917 are largely still in place today. At the very least, the premise that enabled Palestinians’ dispossession remains. Among those forces is a segment of the Palestinian bourgeois elite, who align with whatever power guarantees their interests and privileges.

Jacir, who wrote and directed the film, is clearly attuned to the complex and vital questions tied to that historical moment, yet this is no academic lecture or political tract. Rather, she seeks to show the world—including Palestinians and Arabs themselves—what it means for a largely defenceless people to confront the world’s most formidable powers armed only with instinct, hope, and a legitimate claim to freedom.

Palestine 36 reminds us that what Palestinians faced in the 1920s, 30s, and 40s was a vast British empire with military might, political influence, geographic expanse, colonial ambition, and deep alignment with the Zionist project. In many way, it was not unlike Trump’s America today.

From the outset, the confrontation was never equal. The British brutally repressed Palestinian peasants during that period, setting a template for the means later employed by the Israelis, from killings and mass arrests to exile and the demolition of homes. The film does not merely recount a chapter of the past; it lays bare the enduring architecture of power that has shaped, and continues to shape, the conflict.

Confronting stereotypes

Revisiting the Great Revolt of 1936-39 against the British Mandate carries profound resonance in this context. For decades, it has been suggested that Palestinians relinquished their land in the face of Zionist expansion, or that they failed to grasp the magnitude of the danger bearing down upon them.

The historical record tells a different story: that of a sustained and deliberate uprising against both British colonial rule and Zionist settler colonialism. Distinct in structure yet aligned in purpose, these forces acted in concert, their convergence of interests growing ever more apparent as the revolt unfolded. As one character in the film declares: “Our country is being stolen before our eyes.”

The political slogans and demands voiced during the revolt still resonate. The calls to stop Jewish immigration from Europe, to end the Mandate, and to achieve national independence all reveal a population fully aware of the dangers it faced. The scale of sacrifice confirms this: around 5,000 Palestinians were killed and 20,000 were jailed over three years.

Jacir’s portrayal reflects a careful reading of history, informed by documented research. It likely draws on Ghassan Kanafani’s foundational study, The 1936–39 Revolt in Palestine, and the wider work of Palestinian historian Walid Khalidi.

In Jacir's account, the absence of political clarity rested not with the peasantry or ordinary people, but with specific social and political elites such as business owners, big landholders, politicians, and influential families, many of whom chose compromise, short-term gains, or alliances that protected their status. In doing so, they undermined the popular movement and distanced themselves from Palestinians’ aspirations.

A notable example appears in the British policy of forming a Palestinian militia to target the rebels. This group was ironically named Peace Bands (there would later by a ‘Peace Council’ and today US President Donald Trump chairs a new ‘Board of Peace’). Jacir does not suggest that all Palestinians stood on one side, but shows collaborators who worked with the Zionist Council and with British, whose actions reflect choices made within a system of coercion and advantage.

At the same time, the violence directed at Palestinian villages by colonial troops reveals more than the racial logic of occupation; it is an acknowledgement of the intensity of the resistance and the extent of its support. The general strike that spread throughout Palestine posed a serious challenge to the colonial system.

Repression was wholesale, extending even to those with no direct involvement in the revolt, in part due to the broad social base that sustained the uprising. One scene captures a moment of policy deliberation among the Mandate’s leadership. High Commissioner Arthur Grenfell Wauchope (played by Jeremy Irons) expresses frustration at Christian-Muslim unity and orders the removal of photographs that demonstrate it.

Efforts to reframe national resistance through a religious lens began early and continued thereafter in Western interpretations of Arab liberation movements. Jacir highlights how this strategy was not merely rhetorical, with the Zionist Council financing an “Islamic” association. The aim was to divide Muslims and Christians, cultivate a political mechanism through which to put pressure on the British, and undermine the cohesion of the Palestinian national movement.

Multiplicity of narratives

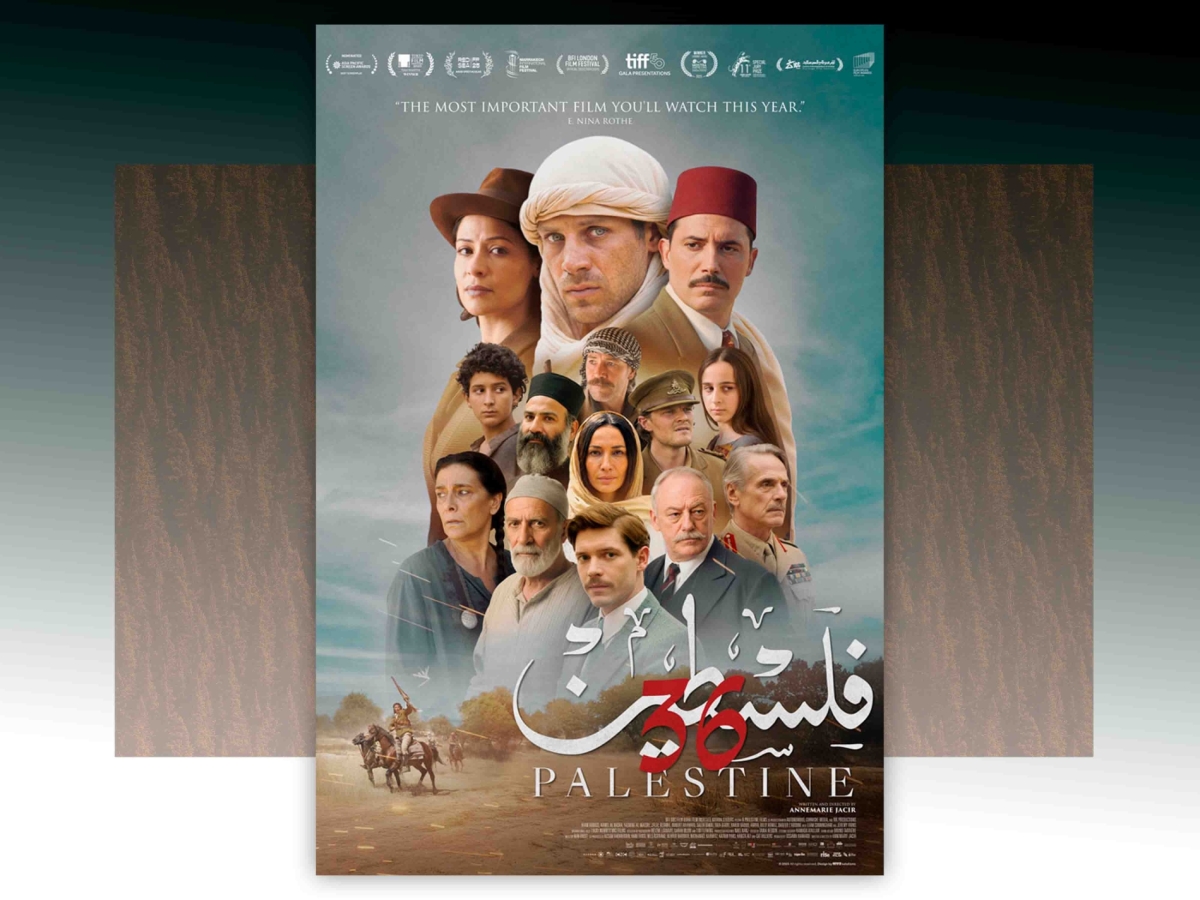

Not seeking spectacle, Palestine 36 draws its power from a commitment to documented history, and unfolds across a dense network of narrative lines. At its centre is young Yusuf (played by Karim Daoud Enaya) who moves between Jerusalem and his village, Basma—a place threatened by settler encroachment and marked for disappearance.