Boredom, frenzy, and unintended consequences await anyone who tries to generate something expressive or artistic through artificial intelligence (AI). Users of generative AI (GenAI) often find themselves in the avant-garde, much against their will. Still, it may be in creators’ interest to follow French poet Arthur Rimbaud’s dictum that “one must be absolutely modern,” as he observed in his seminal book A Season in Hell.

Until three years ago, automatic text generation was an activity reserved either for researchers or for avant-garde writers. Consider the love letter generator created in 1952 by Christopher Strachey, a colleague of mathematician and computer scientist Alan Turing. In the 1960s, the Italian poet Nanni Balestrini used an IBM 7070 mainframe to generate combinatorial poems, including Tape Mark I. More recently, Lillian-Yvonne Bertram’s 2019 collection Travesty Generator turns text generators into a political poetic tool, confronting racism through computational procedures.

As a result, literary criticism has increasingly treated poetry alongside code. This brings both good and bad. For example, it allows the writer to write more fluently in foreign languages, consult more sources in less time, and therefore produce more (and sell more). But this is avant-garde because nobody knows what lies on the frontline of creativity.

Distinguishing the real

In a way, today’s creators feel like painters contemplating the new technology called photography. Some chose to differentiate themselves from the new means of image production, each artist and each movement with its own outcomes, as seen with Monet, Van Gogh, Impressionism, and Cubism. With photography, artists could at least see the photographic image directly, compare it to a painting, and identify the clear visual differences. We can often distinguish a painting from a photograph. By contrast, comparing AI-generated texts with human writing is far more problematic.

There are some differentiators, most notably AI’s tendency to say: “It’s not X, but Y.” For instance: “This isn’t a crisis, it’s an opportunity.” A recent study shows AI uses this construction at least six times more than humans. Yet an extensive survey by the University of Macau and Peking University confirms that no clear distinction exists in linguistic patterns alone, whether analysed by humans or machines. Surface patterns can be disguised. Determining the origin of content (whether AI or human) remains challenging.

This is an informational, scientific, and social concern that demands reflection. By design, these machines are unable to follow orders or instructions, a peculiar incapacity that creates unease. AI cannot respond to orders. It is not even a tool, unlike a hammer or a lever, which does what we physically will it to do. This lack of control over AI is the novelty that should concern us the most.

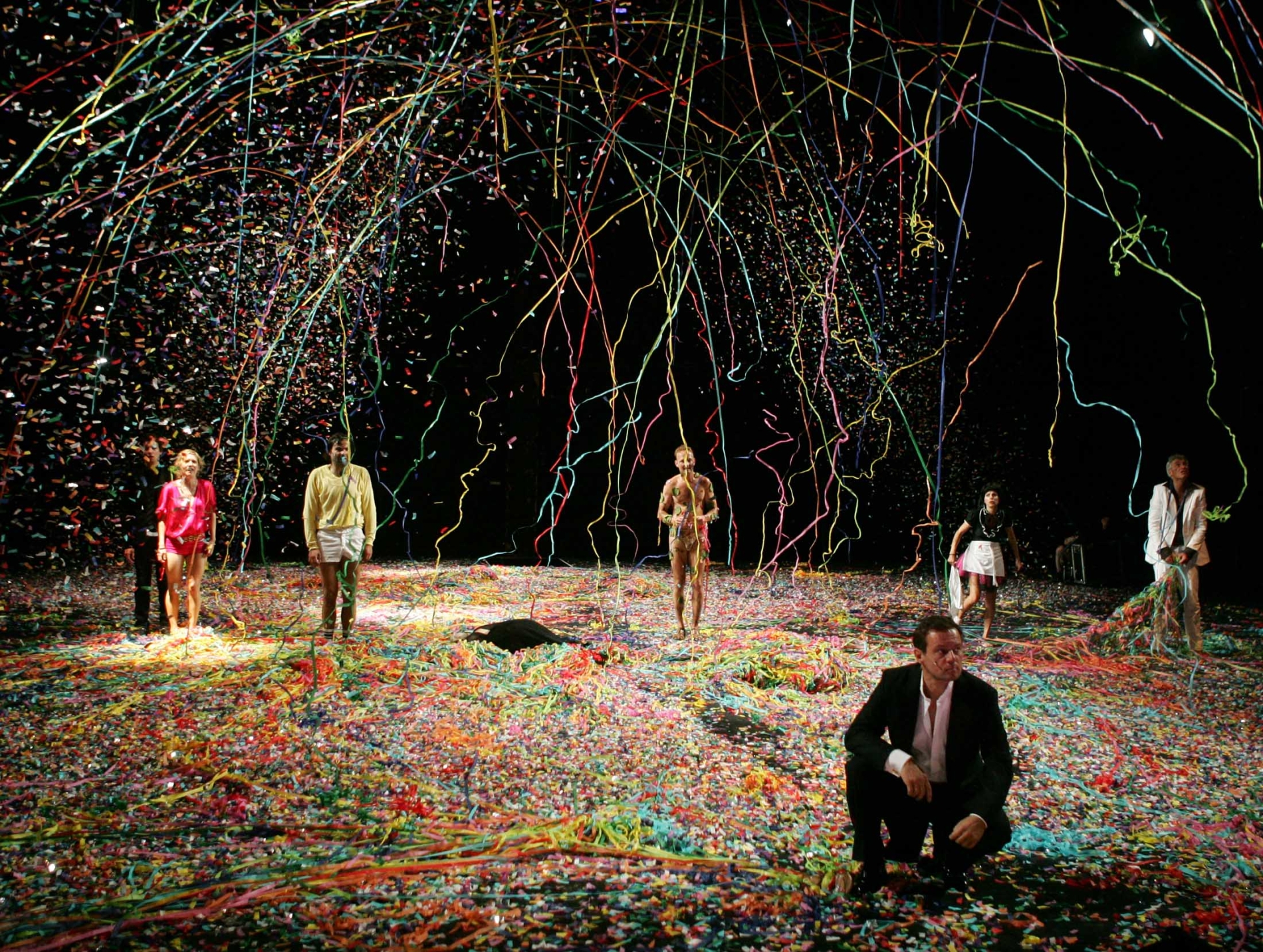

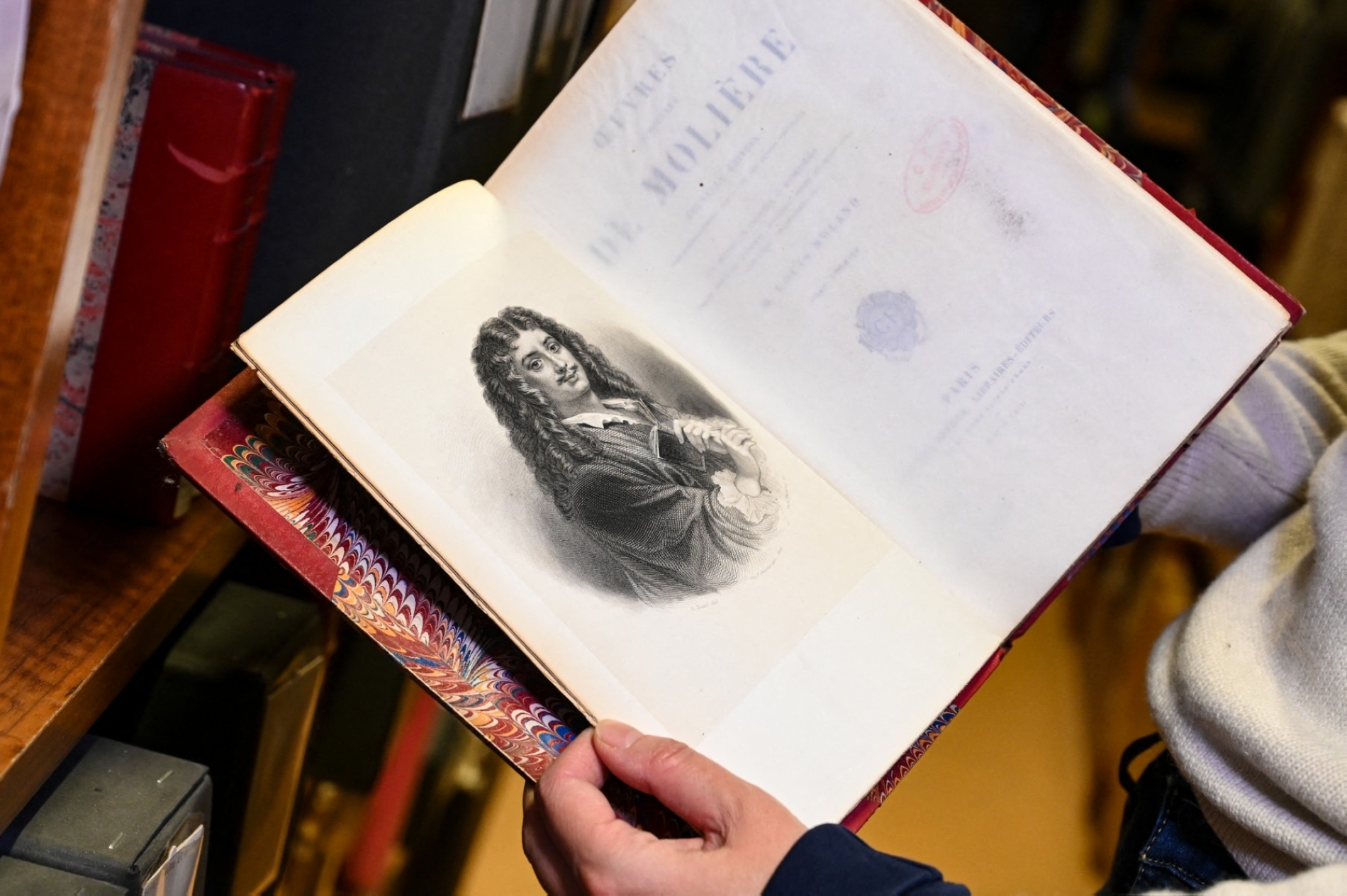

At such a moment, it is apt to channel the mind of French playwright, actor, and poet Jean-Baptiste Poquelin, known by his stage name Molière. L’Astrologue ou les Faux Présages (The Astrologer or False Omens) is a play whose preview excerpt was presented on 10 January 2026, during the closing weekend of the Némo 2025 Digital Art Biennial. It is a text generated by an AI as if Molière were writing (he died in 1673).

Reimagining Molière

The play is part of the Molière Ex Machina project, a collaboration between the digital art collective Obvious—which sold an AI-generated painting for nearly $500,000 in 2018—and scholars from Sorbonne University’s Théâtre Molière. A three-year project, it aims to generate everything with AI, including not just text but costumes, sets, and music, feeding the system historical works and art-historical materials. A fragment of the performance is now available online, and two full performances will take place at Versailles’ Royal Opera in May 2026, performed by flesh-and-blood actors with period accents and period costumes.

As stated in a June 2024 presentation at the Vivatech technology fair, the project uses LLMs (large language models) like ChatGPT, Gemini, Claude, and Mistral, the latter also financing the project. Hugo Caselles-Dupré of Obvious notes that writing a play through prompting might seem easy to anyone familiar with LLMs, but in fact is quite difficult, “especially when you try to reach the level of one of the greatest playwrights in the history of French theatre”.

A true actor-playwright, Molière wrote on the spot, adapting texts to the available sets and his actors’ talents, unlike desk-bound contemporaries such as Racine. “He wrote with exceptional speed,” said the late Georges Forestier, a leading Molière scholar, in an interview for the 400th anniversary of Molière's birth. “It is no coincidence that he wrote The Impromptu of Versailles. The Forced Marriage was also written in just a few days. In The Bores, he adds a scene of 150 lines, the hunters’ scene, in the blink of an eye.”

Working with AI required very different methods, more desk-bound and convoluted. The team drafted 15 versions of the synopsis, each reviewed by a committee identifying imprecisions. Since AI gets lost in complex narratives and produces plot inconsistencies—a well-documented problem as shown by recent research from Autodesk and Midjourney—writing dialogue required extensive back-and-forth with scholars, the team interacting with the AI, using their historical expertise to produce something more plausible.

Style and coherence

As seen in other AI creations, such as the Coca-Cola TV Christmas commercials, what should concern us is not so much the aesthetic result, which has been criticised as soulless, but AI’s problems with style and coherence, and the difficulties in making it generate what we actually want. It seems strange, therefore, that there is a debate over whether AI-generated art counts as art, given these concerns about poor results and questions of coherence.