The Syrian government’s rapid recapture of most areas formerly held by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in under two weeks is not only a stunning military success on the part of the Syrian army, but it is also the result of a series of strategic errors made by SDF leadership.

For years, the SDF built its strategy on the belief that time was on its side, amid a weakening central state under former Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. It wrongly assumed Assad's departure would lead to more chaos and disarray in the country, which would bolster its self-administration model. The government crackdown on Sweida and Israel's swift move to offer Druze 'protection' further entrenched its belief that the country was on the path toward decentralisation and fragmentation.

This led the SDF to make its second mistake. It banked on Israeli intervention in the face of a government assault based on “assurances” conveyed by Israeli officials to SDF leaders. But that support never came. The understandings reached at the Syrian‑Israeli meeting in Paris, attended by American officials and facilitated with Turkish involvement, were a determining factor in Israel's decision not to step in.

The third misjudgement was assuming that Arab tribes—some of which had fought alongside them in the past—would join them in the fight against Syria's new government. But this backing never came, as many saw little to gain from a looming confrontation with the government. This resulted in a swift collapse in the SDF's grip in the northeast, especially in Arab-majority areas east of the Euphrates.

The SDF also bet that Syria's new president, Ahmed al-Sharaa, would fail—not only in his mission to unite the country but also in his efforts to win Western support. This led them to make their fourth mistake: overestimating American support. It didn't believe a new government would come to power in Damascus that could win over US support at its expense.

But al-Sharaa played it right. At nearly every turn, he chose pragmatism over adventurism. This allowed Damascus to reopen diplomatic channels and present itself as a credible partner on issues of security and stability. In November, the Syrian president received a warm welcome at the White House, the first ever for a Syrian president. During his visit, Washington made Damascus its chief partner in the fight against the Islamic State (IS)—an alliance that Syria's Kurds had exclusively enjoyed for over a decade—further weakening its hand.

Read more: The SDF: from chosen US security partner to liability

This showed not only that the SDF severely misread the evolving regional landscape, but also that they overestimated the weight of international guarantees. They naively saw Western backing as unequivocal, despite its poor track record throughout history when it comes to backing the Kurds, only to abandon them when their purpose had run its course.

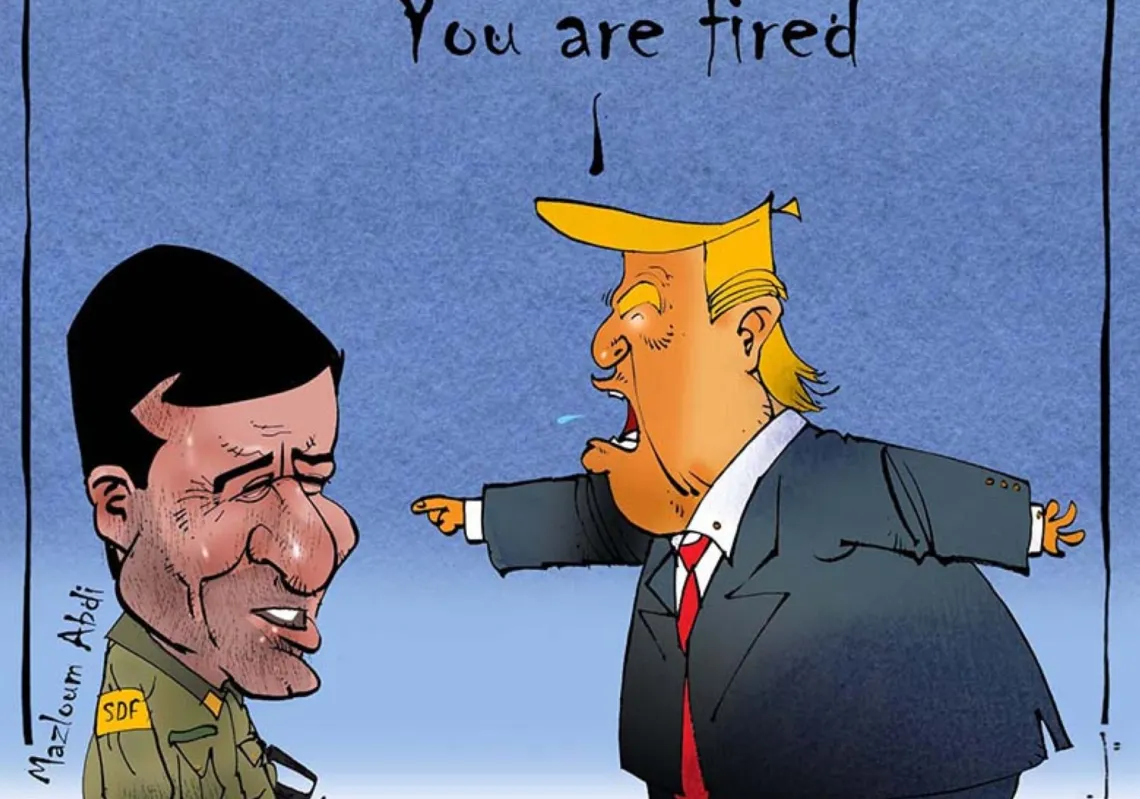

US President Donald Trump—a close ally of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and Benjamin Netanyahu—effectively sold out the Kurds. This was evident in the recent statement by Tom Barrack—the US special envoy to Syria and ambassador to Türkiye—who asserted that the greatest opportunity available to the Kurds lies in “full integration” into the new state and that the rationale for America's alliance with the SDF in combating IS had “expired” with the emergence of a recognised central government, willing and able to take on security responsibilities and now part of the international coalition against the group.

The conclusion is crystal clear: Washington sees no benefit in a prolonged military confrontation and no avenue towards separation or federalism. The focus has shifted towards integrating the SDF and shifting responsibility for IS detention centres, camps, and strategic assets to Damascus.

Moving forward, the Syrian government faces four critical tests that will determine the viability of the post-conflict period. The first is the threat of an IS resurgence, especially amid reports of prison escapes. The second relates to the presence of PKK fighters alongside the YPG in some Kurdish-majority areas, a matter that raises serious internal and regional sensitivities, particularly in relation to Türkiye.