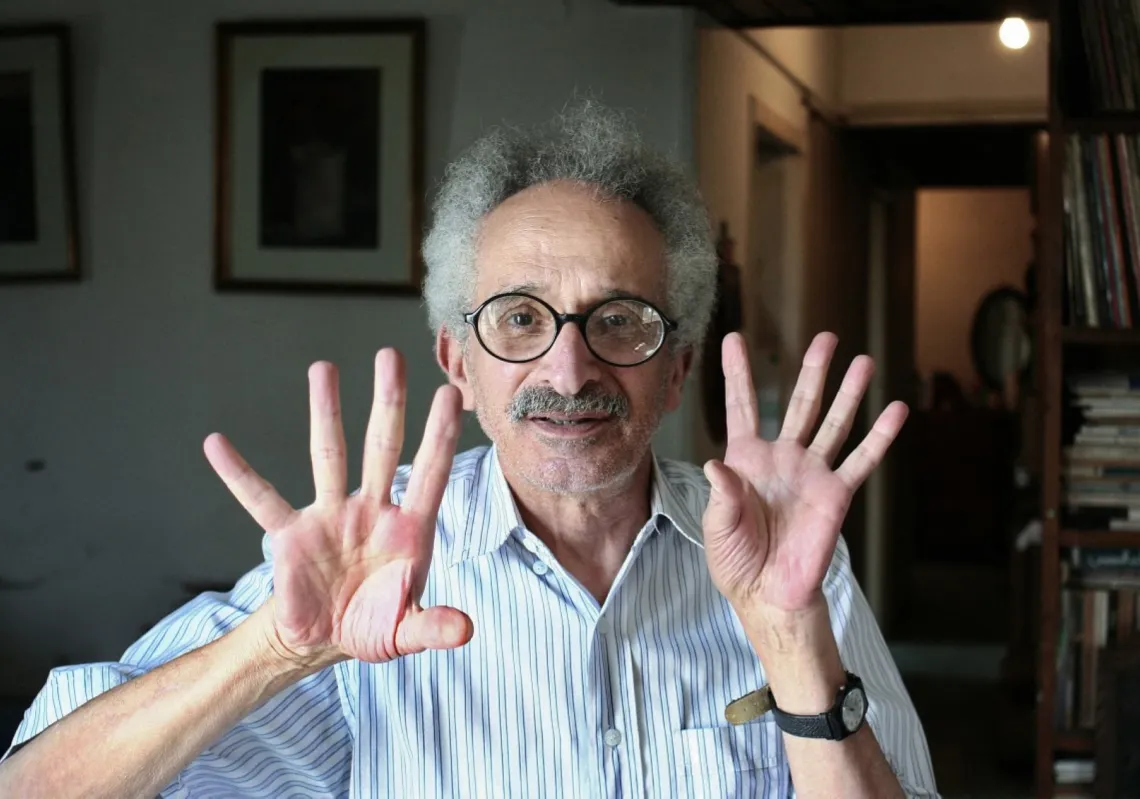

At the end of November, Egyptian novelist and writer Salwa Bakr became the first laureate of the BRICS Literature Award, crowning a literary career that began four decades ago when she published her first collection of short stories. The award was presented in the city of Khabarovsk, in Russia’s far-east, and Bakr’s prize included one million Russian rubles—around $12,600. The awarding committee described her as “one of the leading figures in contemporary Arabic prose”.

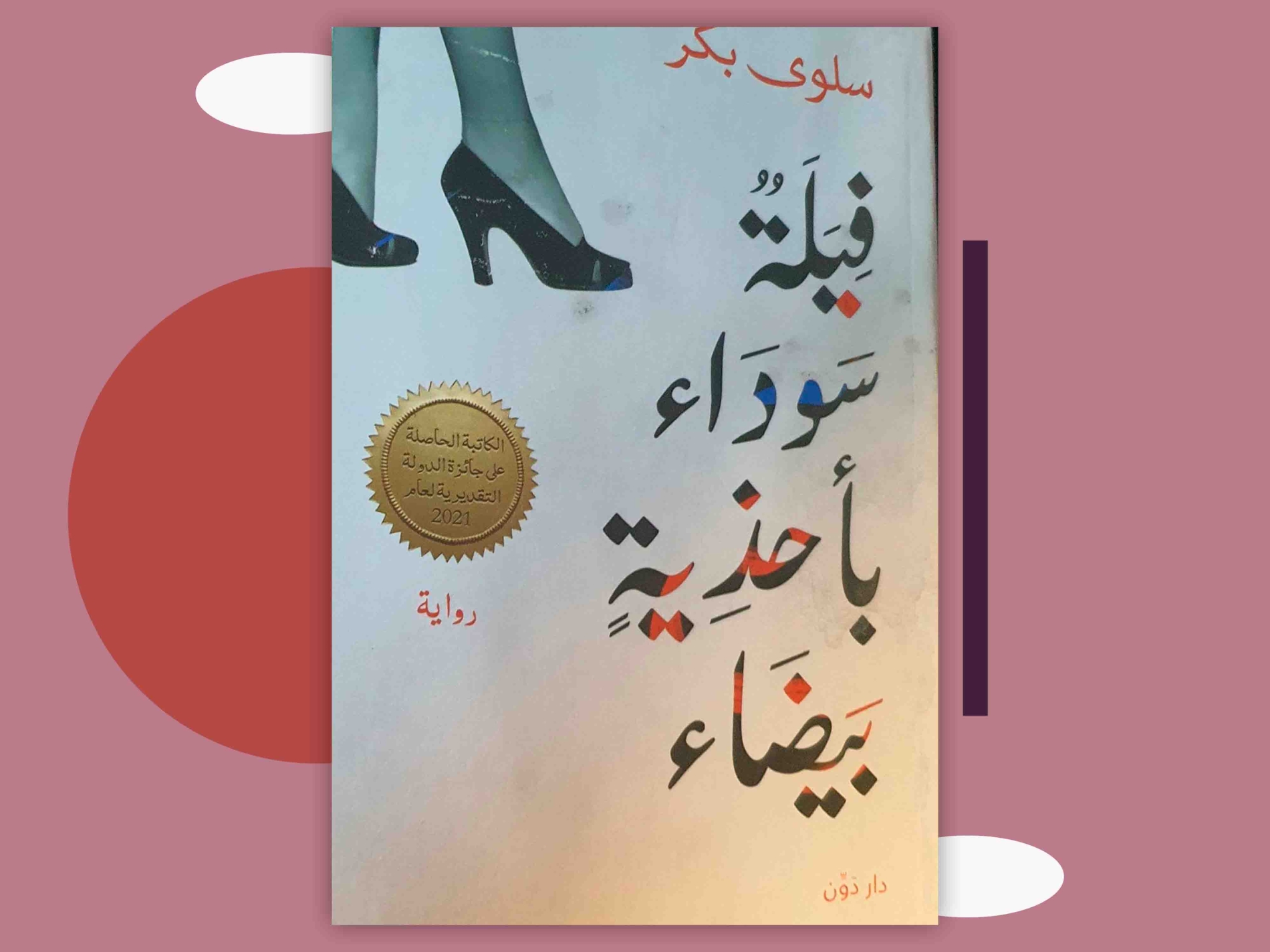

The author of seven short-story collections, seven novels and a play, whose works have been translated into numerous European languages, Bakr was born in Cairo in 1949, studying business at university before also studying theatre criticism. Upon entering the world of cultural journalism, she began as a film and theatre critic for various Arab publications, before devoting herself full-time to creative writing.

Her first short-story collection, Zeinat at the President’s Funeral, appeared in 1985, followed by several others. In 1991, she published her debut novel, The Golden Chariot Does Not Ascend to Heaven, a work rooted in the lives of the marginalised and the overlooked. Al Majalla spoke to Bakr about her literary journey and the significance of her recent award. Here is the conversation:

Was it a deliberate decision to start writing, or was it a path that unfolded gradually?

Literature was never a planned choice. It was a childhood passion. I read literature and history, and writing was something I approached with awe for years. I grew up in a period of fine translations, and the works of great writers were widely available, which raised the standards of taste and made the first step more difficult. The first book that truly captivated me and drew me into storytelling was Kalila wa Dimna.

After graduating, I worked for six years as a government inspector, monitoring market prices. Then I began to write, though I dared not publish, for fear that my texts might not be good enough. One day, my friend Shaaban Youssef asked whether I knew anyone who wrote short stories. I told him that I did and gave him some of my work. He showed them to the late Yahya Taher Abdullah, who knew me as a reader, not as a writer. That’s where my journey with writing began.