In his most recent work, the France-based Yemeni novelist Habib Abdulrab Sarori has turned his attention to what he calls the “novel of contemplative imagination,” a genre notably rare in Arabic literature.

In this interview with Al Majalla, the computer science professor reflects on his three novels through this lens, explores the current state of contemplative, scientific, and language-driven fiction in the Arab world, and considers how the legacies of Ibn Tufayl and Abu al-Alaa al-Ma’arri can be drawn upon today.

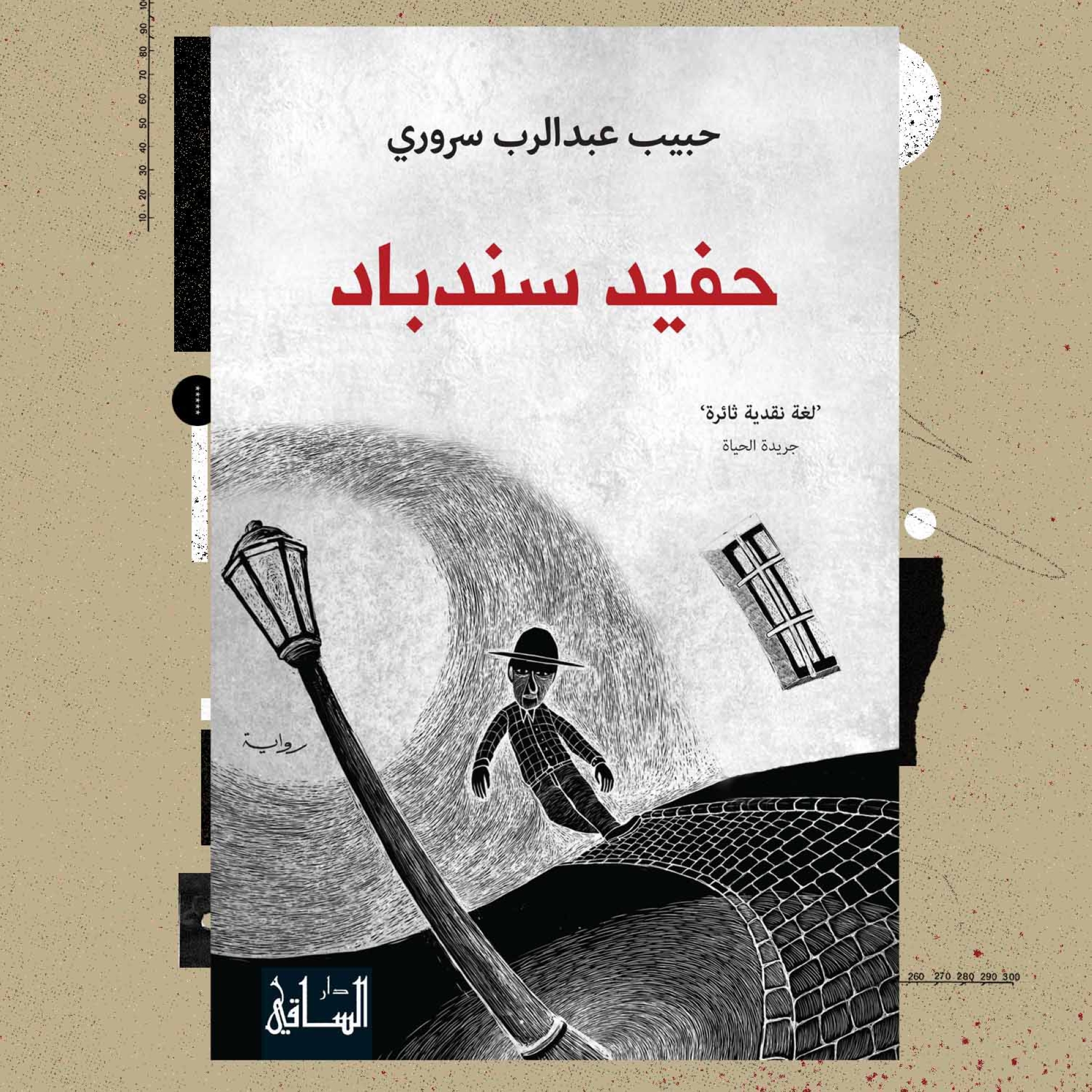

In your last three novels—Hafid Sinbad, Jazirat al-Mutafafin (The Island of the Defrauders), and Exodus—you combine social realism with ‘contemplative imagination’. Why has this literary mode emerged so late in Arabic writing?

The main reason for this delay, in my view, is the weakness of scientific culture in particular, and cultural illiteracy in general. We should not forget that in the West, science has become the guiding compass of society’s thinking. Before the Age of Enlightenment, this role belonged to religion. Today, science is present not only in schools but also in museums, the media, and public events—such as those that celebrated the bicentennial of Charles Darwin’s birth and the 150th anniversary of the publication of The Origin of Species. It is not surprising that the most significant public events in recent years have been scientific ones.

In this environment, it is natural for science to be abundantly present in Western fiction. Many of Michel Houellebecq’s novels, for example, fall under the category of ‘contemplative imagination’, and he himself was an engineer and programmer before entering the world of literature. Science has also permeated Western languages. In contemporary French, one can describe a very energetic or restless person by comparing them to a particle accelerator. Who would understand you, or even enjoy hearing such a phrase, if you were to say that in Arabic?

Did you approach your three novels with specific guiding principles that you regard as essential to the framework of contemplative imagination?

Each of my novels has its own birth story. There were no predetermined frameworks, only sparks and questions, accompanied by a desire for new narrative experiments and a search for the joy of imagination in untouched worlds. For example, Jazirat al-Mutafafin emerged when, at the start of the pandemic, I found myself in Calais, where migrant boats secretly depart for Britain. I was there to write a literary article about them for a German author. Exodus began with a fascinating technical question that captured my imagination, leading to a moment of laughter with a researcher friend as we wondered about the possibility of having children outside the pull of Earth’s gravity.

Are you afraid that this narrative approach reflects a kind of ‘scientific determinism’?

There is an ongoing scientific and technological progress in human life today that no one can deny—the determinism of progress. A Marxist idea, once seen as the defining feature of the age, differs little from religious imperatives that leave no room for alternative expressions. I personally have argued against colleagues who believe in this utopian inevitability. There is no inevitability. It is enough to note that contemporary Western generations are the first to feel their lives are worse than those of their parents. And what can we say about Arab youth? We must also remember what industrial modernity, driven by selfish policies that ignore the environment and deny scientific warnings about the future of the climate, has brought upon our beloved planet.

The future is deeply uncertain, and this is precisely what I try to highlight. We need one eye fixed critically on the past, since our history has been distorted by the victors, and another eye towards the future, trying to anticipate it and recognise its dangers. This is a concern I constantly return to in my fiction. All three novels carry strong warnings about the catastrophes ahead. In Hafid Sinbad, the ending is less dystopian and suggests, even if timidly, a possible reconciliation between technology and mythology. Jazirat al-Mutafafin ends in a purely dystopian vision, though it still contains stubborn heroes and a glimmer of hope. In Exodus, environmental collapse reaches such an extreme that humanity begins to seriously consider migrating beyond our planet. But what would it mean to have children outside Earth’s gravity?

Beyond these broader settings in which the novels unfold, I remain primarily interested in the characters’ lives and the evolution of their relationships. Once the structure is in place, the characters begin to shape their own paths almost independently. The five protagonists of Exodus are an exemplary case. I never expected their stories to take the direction they did when I first began writing the novel.

Almost 200 years ago, Mary Shelley imagined a human assembled from various body parts in her novel Frankenstein. In the end, this creation rejects the form in which it was made. Do you worry about humanity’s future as technology and biotechnology begin to play a dominant role?

Technological development is a double-edged sword. What I hope for is a harmonious evolution of artificial and human intelligence, guided by humanity’s interests rather than capital’s. Artificial intelligence, which is no less important or dangerous than state-run nuclear power, is now largely in the hands of bold and reckless Silicon Valley youth whose wealth exceeds that of nations, and this is truly alarming.

I hope that the robots of the future resemble the one in my novel Hafid Sinbad: Bahloul, who developed independently, later changed his name to Haidar because he disliked his original name, and eventually became autonomous yet remained a loyal companion to his narrator, unlike the creature in Frankenstein, who turned against his creator. Since Isaac Asimov’s era, our imagined relationship with civilian robots has become more humane. On the other hand, I am against lethal autonomous military robots, like those in Jazirat al-Mutafafin. I have long been aware of the dangers of this kind of artificial intelligence, which has already become a reality.

How do you see the role of ideology and intellectual engagement in your novels, where the narrative often reflects an enlightening ‘School of Life’ approach?

I truly believe that the novel is a school of life, according to the meaning of ‘school’ in my own dictionary. It is not a place for indoctrination but a space where questions erupt, and the method of doubt develops. The novel is, by its nature, distant from religious or political ideology. The school of life, as I understand it, is broader than formal schooling and far more experiential. Through fiction, we merge with others’ experiences, draw inspiration from their suffering, and recognise in them aspects of human nature that academic knowledge alone cannot reveal. For this reason, the modern novel has played an important role in the human revolution that has shaped the ethics of the human rights era.

In addition, some of my novels openly venture into the realm of what I call spiritual wars, such as Wahi (Revelation) and Aarq al-Aliha (Lineage of the Gods), where ideas inevitably collide. This is something the Western novel has embraced since the time of the French philosopher and novelist, Voltaire, and it has contributed greatly to the civilisational progress of the West. The Arab novel is still hesitant to enter these territories because of the violence of reactionary forces and the narrow limits of freedom, even though this is something we Arabs need now more than ever.

Yet, when my novels enter these thorny intellectual spaces, they allow different visions to confront one another, as in Wahi. Or they weave philosophical reflection into a narrative thread softened by love, as in Aarq al-Aliha, where the protagonist navigates his fiery and divided love for the poet Ferdowsi and the neuroscientist Hanaya.

Is this why you draw on Arab figures from history in your writings, such as Abu al-Alaa al-Ma’arri?

Al-Ma’arri was a novelist par excellence. Riwayat al-Ghoufran, which he wrote as part of Risalat al-Ghoufran, is a fictional treasure that deserves deep exploration in the Arab world, much as the West has engaged with Dante. He stands as our most modern and profoundly classical writer. Al-Ma’arri is also the protagonist of my novel The Hoopoe Report, where the fictional imagination stretches far beyond his real biography and ideas. In the novel, he has a secret love affair with his student Hind, while his thirty-third descendant, living in the present day, serves as the narrator.

Can Hayy ibn Yaqzan by Ibn Tufayl and Risalat al-Ghoufran by al-Ma’arri be considered part of the tradition of contemplative imagination?

The modern understanding of speculative fiction is tied to a proactive form of imagination, often moving between the present and the near future, with a focus on deriving future scenarios from the present. This is, of course, very different from traditional science fiction, which tends to concentrate on technological details or entirely imaginary cosmological worlds. In this sense, we are within the framework of the modern novel, concerned with worldly matters since the time of Cervantes’ Don Quixote. However, if we take the concepts of ‘imagination’ and ‘meditation’ outside the modern novel and this narrow definition, we find a rich presence of both in Ibn Tufayl’s Hayy ibn Yaqzan and al-Ma’arri’s Risalat al-Ghoufran, even though the challenges they explore differ significantly.

In al-Ma’arri’s reflections, there is a modernity that deserves attention, often overlooked by some Arab critics who see only intellectual labyrinths or contradictions. I refer here to the plurality of meanings al-Ma’arri presents when exploring metaphysical questions, particularly in Risalat al-Ghoufran. These questions are ‘undecidable’, grounded in religious hypotheses rather than scientific reasoning. Nothing is richer or more beautiful than approaching them through multiple interpretations rather than taking a definitive stance on religious belief. Narrow readings lead some to label al-Ma’arri as an atheist heretic, while others see him as a devout Muslim, demonstrating the spectrum of possible interpretations.

Writing with such polysemy is an art—one mastered by great writers, especially contemporaries, when exploring the unseen as novelists—Jean d’Ormesson, for instance—or in artistic form, as in Nicolas Poussin’s Et in Arcadia ego, which continues to inspire countless interpretations to this day. Al-Ma’arri achieved this metaphysical artistry very early. When he said, “As for God, it is something that I do not understand,” he did so with remarkable success, opening multiple avenues of interpretation through the layered text of his novel.

Narratively, there is great richness in conveying messages tied to diverse hypotheses, especially religious ones. A writer becomes a ‘shepherd of meanings’, allowing for a plurality of interpretations. As readers, we must accept multiple readings of esoteric topics. Perhaps al-Ma’arri exemplified this in his famous verse: “The inhabitants of the earth are of two sorts: those with brains, but no religion, and those with religion, but no brains.” Here, the distinction is not based on faith or atheism but on rigid certainty on one hand and questioning, doubt, and critical reflection on the other.