In the weeks leading up to the invasion of Iraq in 2003, the region stood on the cusp of a historic transformation. The invasion profoundly ruptured the Middle East's structure and fundamentally altered how the West managed its relationship with the region. Recently released British documents detailing political exchanges with Amman offer a rare glimpse into that critical moment—not only through the lens of its consequences, but also from within the chambers of strategic thought at the time.

These documents offer a rare window into the thinking of the power structures preparing for war, and of Jordan's efforts to keep diplomacy alive in order to blunt the blow of what was coming.

The meeting between King Abdullah II of Jordan and then Prime Minister Tony Blair in London in February 2003 must be understood within this context. It was not a courtesy visit, nor a ceremonial stop. It was a moment of political urgency—where grand strategic calculations collided with immediate regional anxieties, and where the tension between the logic of force and the logic of stability was laid bare.

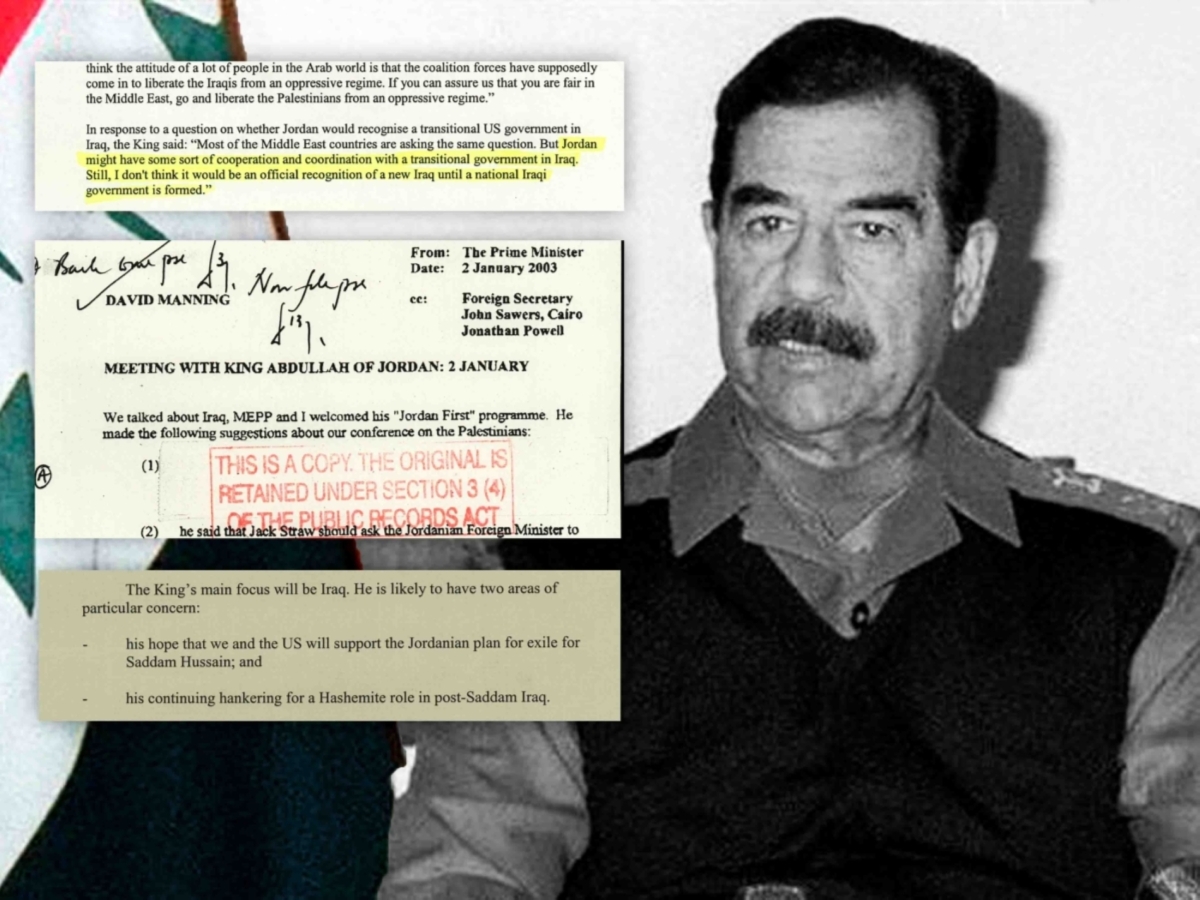

One of the most striking aspects of these files is the nature of the documents themselves. A significant portion is not composed of actual meeting records, but of preparatory papers drafted by the Prime Minister’s office in anticipation of high-level encounters. These were written by Jonathan Powell, Blair’s private secretary and head of his political office. As such, they don't record what was said, but rather what was expected to be said—and also what Blair needed to be prepared to respond to. This shows that London was aware its regional allies weren't completely on board with its plan to invade Iraq.

One document notes that King Abdullah would likely raise the issue of Iraq and seek a political alternative to avoid war. The drafter wrote: “The king is likely to want to discuss Iraq, including the possibility of offering Saddam exile as a way of avoiding war.”

This shows the UK was aware of Jordan’s concerns. It also shows that, although Amman understood the limits of its power, it nevertheless sought to influence Western powers into halting its military invasion.

In the same document, the drafter inserts his own view that “He (King Abdullah) may also have a hankering for a Hashemite role in post-Saddam Iraq.” While this does not convey anything the Jordanians actually said, it reflects the thinking in official British circles. This British supposition, expressing London’s early preoccupation with the post-Saddam order and the political vacuum that the regime’s collapse would leave behind, reflects British anxiety about managing “the day after”.

The draft immediately instructs Blair to avoid any discussion of a Hashemite role in Iraq and to affirm that the country's future governance is a matter solely for the Iraqi people. This reveals an early British sensitivity to any suggestion of foreign-engineered political outcomes in Iraq.

When moving from the preparatory documents to the official meeting summary drafted after the encounter, the tone changes markedly. Conjecture and internal analysis fall away, and the focus turns to what was actually said.

A diplomatic off-ramp

In the summary dated 26 February 2003, Jordan’s position is articulated with clarity. King Abdullah II is recorded as having firmly offered a diplomatic off-ramp until the final moment. The document notes that he proposed offering exile to Saddam Hussein as a last-ditch attempt to avoid war. He is quoted as saying: “If Saddam accepted exile, there would be no need to fire a single shot.” This reflects the king's belief that war was not inevitable and that he could persuade Western powers to reconsider their decision to go to war.

Direct link to Palestine

What stands out in the summary of the Blair–Abdullah meeting is that Iraq was not treated as an isolated issue, but was firmly situated within a broader regional framework. The document records a direct link made by the king between the impending war in Iraq and the Palestinian question, warning of the broader implications: “Any new conflict in the region would have serious repercussions on the Palestinian issue and wider regional stability.”

This shows that Jordan never viewed Iraq as a standalone crisis, but as an issue intrinsically tied to Palestine and to the prevailing regional mood that viewed war on Iraq as another regional crisis handled through force rather than addressing the underlying causes of conflict.

The documents also reveal the complexity of the British position at the time. While London had already committed to standing alongside Washington, it remained acutely aware of the potential regional costs of war. And while this awareness didn't alter its course, it was careful to acknowledge and record concerns in a measured and detached manner.

Despite the UK's apparent awareness of the consequences of launching a war on Iraq, there was a fundamental gulf between the logic of force that governed the moment and the logic of stability that regional capitals such as Amman sought to preserve, which simply couldn't be bridged.

But perhaps what the files omit is more revealing than what they include. Scenarios mentioned in the preparatory material do not appear in the official meeting summary, reflecting the gap between what is theorised behind closed doors and what is formally placed on the political table—between private analysis and public articulation. This disparity lends the documents additional historical value. They not only reflect what was said, but also hint at what might have been said and what was withheld.