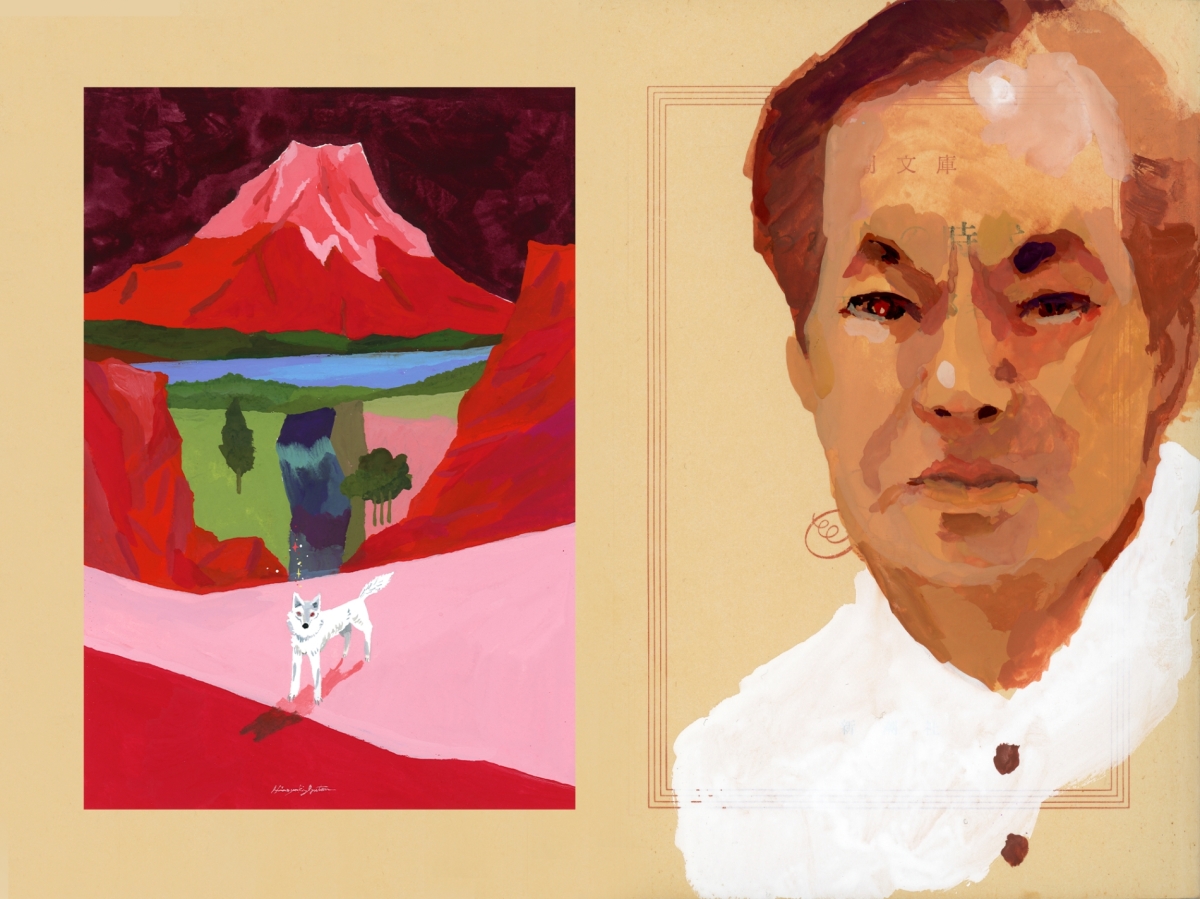

Banya Natsuishi is widely regarded as one of the most distinguished poets of contemporary Japan—a leading figure in the practice and global dissemination of haiku, a Japanese form of poetry with a three-line structure. His work embodies the refinement of tradition and the boldness of innovation, positioning haiku both as a Japanese art form and as a universal poetic language.

Born in 1955 in the city of Aioi, nestled within Japan’s Hyōgo Prefecture, Natsuishi was originally named Masayuki Inoue. When he was 14, his first haiku was selected for publication in a monthly journal by Tōta Kaneko, a revered master some consider the greatest haiku poet of his time.

In 1975, Natsuishi moved to Tokyo, where he encountered two of the era’s most avant-garde haiku poets—Kaneko and Shigenobu Takayanagi. They would both have a huge effect on him. Natsuishi studied French literature and culture at the University of Tokyo, earning a master’s degree in comparative literature in 1981. In 1992, he was appointed professor at Meiji University, a position he continues to hold.

That same year, he was awarded the 38th Modern Haiku Association Award. From 1996-98, he was a visiting scholar at the University of Paris VII. In 1998, together with poet Sayumi Kamakura, he founded the international haiku journal Ginyu (The Travelling Poet, or The Troubadour), becoming editor-in-chief. The following year, he co-organised the First International Symposium on Contemporary Haiku in Tokyo. This led to the establishment of the World Haiku Association in 2000. Today, he is a director of the Modern Haiku Association of Japan and lives in Fujimi, near Tokyo.

Natsuishi has published eight haiku collections, among them Daily Hunting Diary (1983), Rhythm in Emptiness (1986), Opera in the Human Body (1990), Pilgrimage on Earth (1998), and The Flying Pope in the Sky (2010). His editorial contributions are equally notable, with works such as A Guide to Haiku in the 21st Century (1997), Multilingual Travelling Haiku Poets (2000), and The Transparent Current (2000). His critical writings include A Dictionary of Keywords in Contemporary Haiku (1990), A Guide to Contemporary Haiku (1996), and Our Friend, the Haiku Poem (1997).

Much of his poetic output has been translated into English and other languages. Here is his conversation with Al Majalla:

Could you introduce yourself to Arab readers?

I am a poet, philosopher, and haiku artist. My creative path is rooted in haiku, which I regard as the purest and most inventive form of linguistic expression—a distillation of poetic essence that transcends boundaries.

What makes a person a poet? And how does this apply to haiku, given its growing reach and renown?

A true poet can detach from all things and all people yet still forge connections among them through a language that is both generative and suggestive. Terms like ‘global’ and ‘famous,’ I confess I do not fully grasp their meaning. They strike me as vague constructs—illusions particularly cherished in the American imagination.

Your haiku often engages with global political realities, as in your line: “Newspapers absorb a great deal of blood.” Is this a novel direction for haiku?

In the English-speaking world, Japanese haiku is often oversimplified or misunderstood. The haiku you mention speaks to the insidious power of propaganda embedded in journalism. It is rare to find a haiku that dares to critique the edifice of human culture.

What draws you repeatedly to this poetic form?

Writing haiku brings me joy—not because it offers solace, but because it reveals a bitter awareness of the frailty of human existence and the impermanence of nature. And yet, in that very awareness, I find the will to live on, and with it, a renewed intuition.

What inspired the founding of the World Haiku Association in 2000, and how do you see its role today?

The World Haiku Association was founded in Slovenia in September 2000 and re-established in December of the same year.