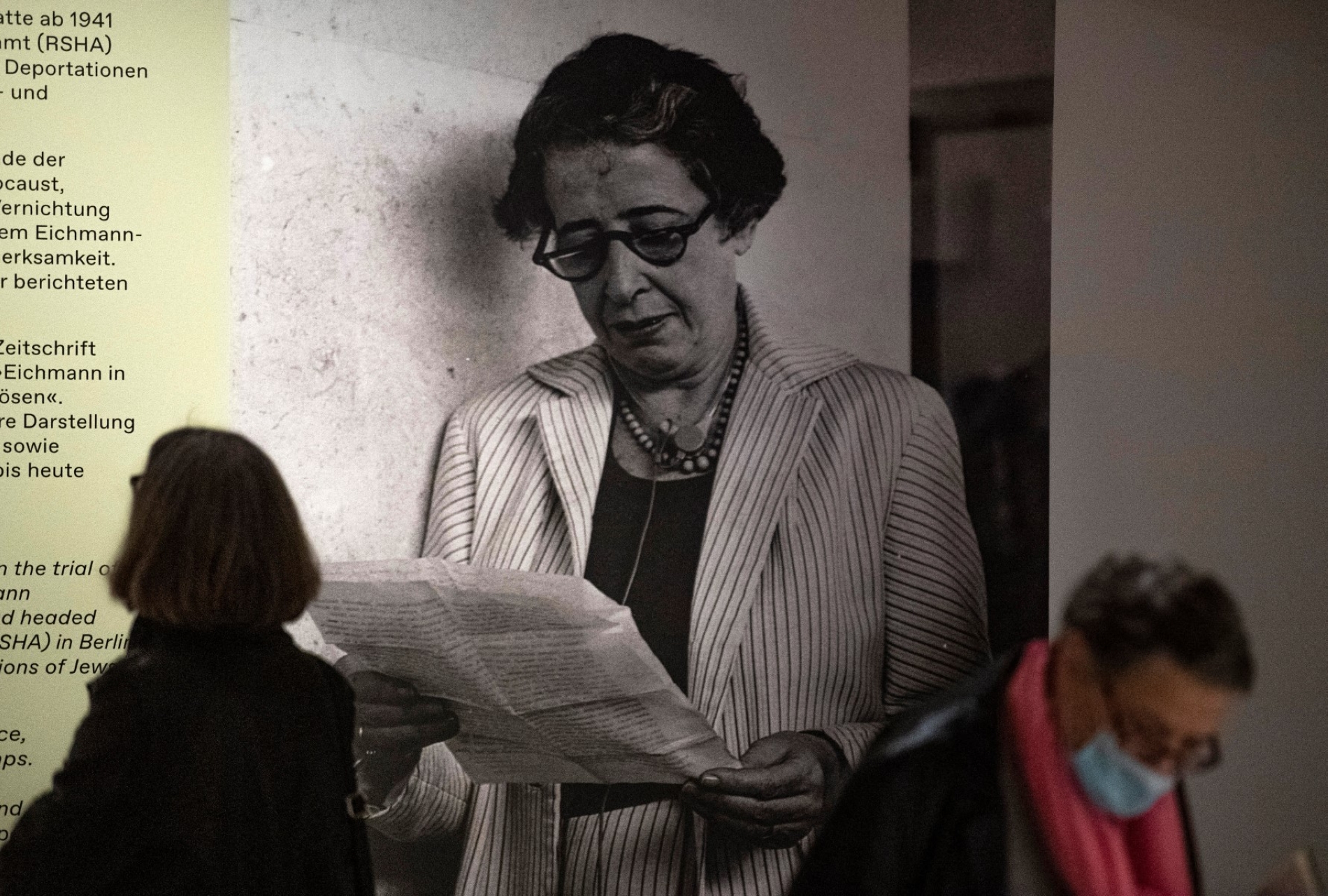

Today marks 50 years since the passing of German-American philosopher Hannah Arendt, whose analyses of totalitarian regimes provided an exact portrait of politics and ideology in the 20th century and beyond. Their ways of thinking and acting were examined in rich and vivid detail, especially in works such as The Origins of Totalitarianism, The Human Condition, On Violence, What Is Politics, and Eichmann in Jerusalem.

After the 1971 publication of the US Department of War’s secret documents on the Vietnam War, known as the Pentagon Papers, Arendt turned her attention to the functions and uses of falsehood. Those papers had exposed the lies of the Lyndon Johnson administration. She observed that secrets—what diplomatic language terms the hidden workings of power, its puzzles and deceits, as well as deliberate distortion and sheer fabrication—had been present throughout history.

Truth had never constituted a political virtue. For this reason, Arendt held that viewing politics through a truth-centred lens places us outside history. On this basis, she urged us to view politics from the perspective of falsehood, which, in political affairs, is considered a legitimate means.

Falsehood is a familiar tool in the hands of rulers and a recognised device among diplomats. In this sense, it has always been regarded as permissible.

A reality subordinated to ideology

In the 20th century, falsehood underwent a transformation in its very nature. According to Arendt, it had previously concerned only those who had not sought to deceive the entire world. It aimed only to alter partial events. It had consisted of scattered holes in the fabric of facts. It had not amounted to a distortion capable of transforming the entire context within which events occur.

With the emergence of totalitarian regimes, however, falsehood expanded in scope. Reality as a whole became wrapped in propaganda and subordinated to, and moulded by, ideology. Anything that refused such subordination was set aside and eliminated. In contrast to the limited falsehood once practised by diplomatic channels, which took into account confidentiality and the nuances of deception, falsehood was enacted openly before all, even in relation to events whose factual nature was scarcely hidden from anyone.

Among the transformations that falsehood underwent was the use of truth itself. Arendt pointed to what she described as a distinctly Machiavellian technique mastered by Adolf Hitler. He would state the truth, knowing that anyone unfamiliar with the hidden meanings or codes behind his words would dismiss them as unbelievable or irrelevant. This amounted to a conspiracy conducted in broad daylight. Arendt often considered this to be the clearest expression of the falsehood that defines our age—telling the truth in a way that deceives people who assume they do not need to question or distrust it.

She believed this contemporary form of falsehood transcended individual and moral domains. It was collective and political, leaving its imprint on history. Modernity may be linked to this radical transformation of the nature of falsehood, especially political falsehood, for it no longer functions as a cover concealing truth. It has become a final obliteration of reality and a practical destruction of its original documents and records.

Falsehood thus ceased to be the concealment of truth. It became the eradication of truth. It ceased to be a historical ruse. It became a ruse practised upon history. Perhaps the most widespread mechanism of falsehood in this regard is the turning of history into myth; the extraction of an event from its circumstances so that it becomes an endlessly repeated beginning, a memory that continually revives and persists.

‘Legitimate’ falsehoods

Arendt went further than merely describing how totalitarian regimes falsified facts, implanted falsehoods, and contrived to outwit history. She spoke of the lies regarded as necessary and legitimate instruments in the service of political actors, regardless of the systems within which they operate. Such lies enable these actors to interpret events in accordance with the dictates of the moment and the demands of circumstance.

Falsehood can afflict democracies, too. Even in what is termed the ‘free world’, entire nations can be steered by a web of deception. In this respect, it is essential to note the role of the media, and both official and unofficial propaganda, in colouring historical events to suit need and circumstance, opening the way for comprehensive falsehood. It is a danger born of the modern management of facts—a danger applicable to democratic systems as much as to totalitarian ones.