In October, Grendizer turned 50. Yet the spacefaring robot remains as youthful and unchanging as he was when his first episode aired on Japan’s Fuji TV on 5 October 1975. Today, as the world marks half a century since the birth of this animated legend, he continues to hold a special place in the hearts of millions, especially those from across the Arab world.

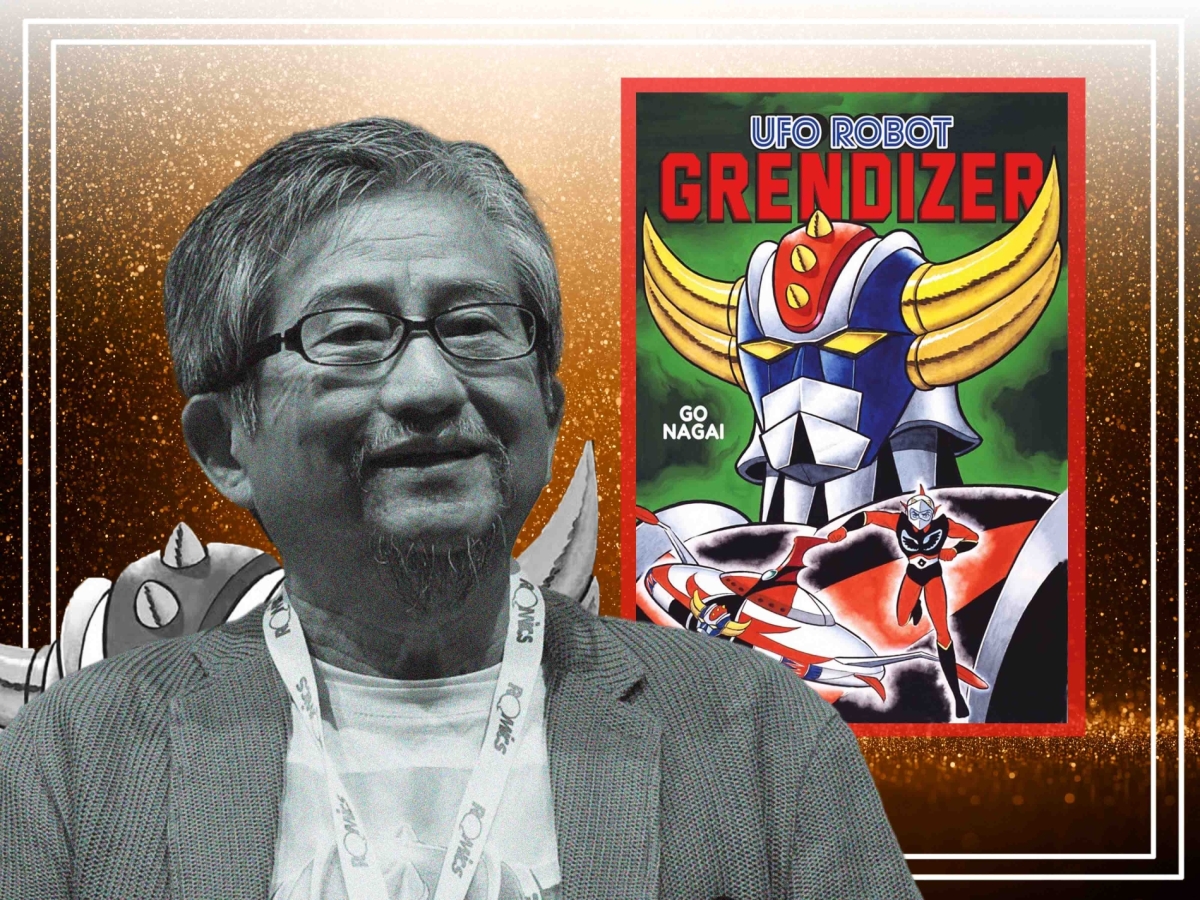

In July, Japan Expo Paris, the largest festival of Japanese culture in Europe, named Grendizer its ‘character of the year’ and created a sprawling exhibition called ‘Grendizer, Go! Fifty Years of Legend’. Spanning more than 300 square metres, the exhibition offered a sweeping visual chronicle of the character’s journey—from the early sketches of creator Go Nagai and original production materials from the 1970s to the height of Grendizer’s popularity across Europe and the Arab world.

Meanwhile, in Japan, a series of luxury limited-edition releases were unveiled, chief among them the ‘Tissot Grendizer: Fifty Years’ timepiece, announced in September. Only 1,975 units were produced—a symbolic nod to the anime’s debut year. The watch features a second hand shaped like Duke Fleed’s iconic Double Harken and is housed in a case modelled after the legendary Spazer craft, bearing Nagai’s signature.

Amid this global fanfare, Grendizer returned to the screen after more than four decades of silence. In July last year, Grendizer U premiered, a new production co-developed and marketed by Saudi Arabia’s Manga Productions. The new series preserves the spirit of the original narrative and its core characters while introducing a reimagined setting and updated animation that blends nostalgia with modernity. A companion series, Grendizer U: Origins, authored by Nagai himself, is slated for release in March next year and will explore the Grendizer universe with fresh eyes.

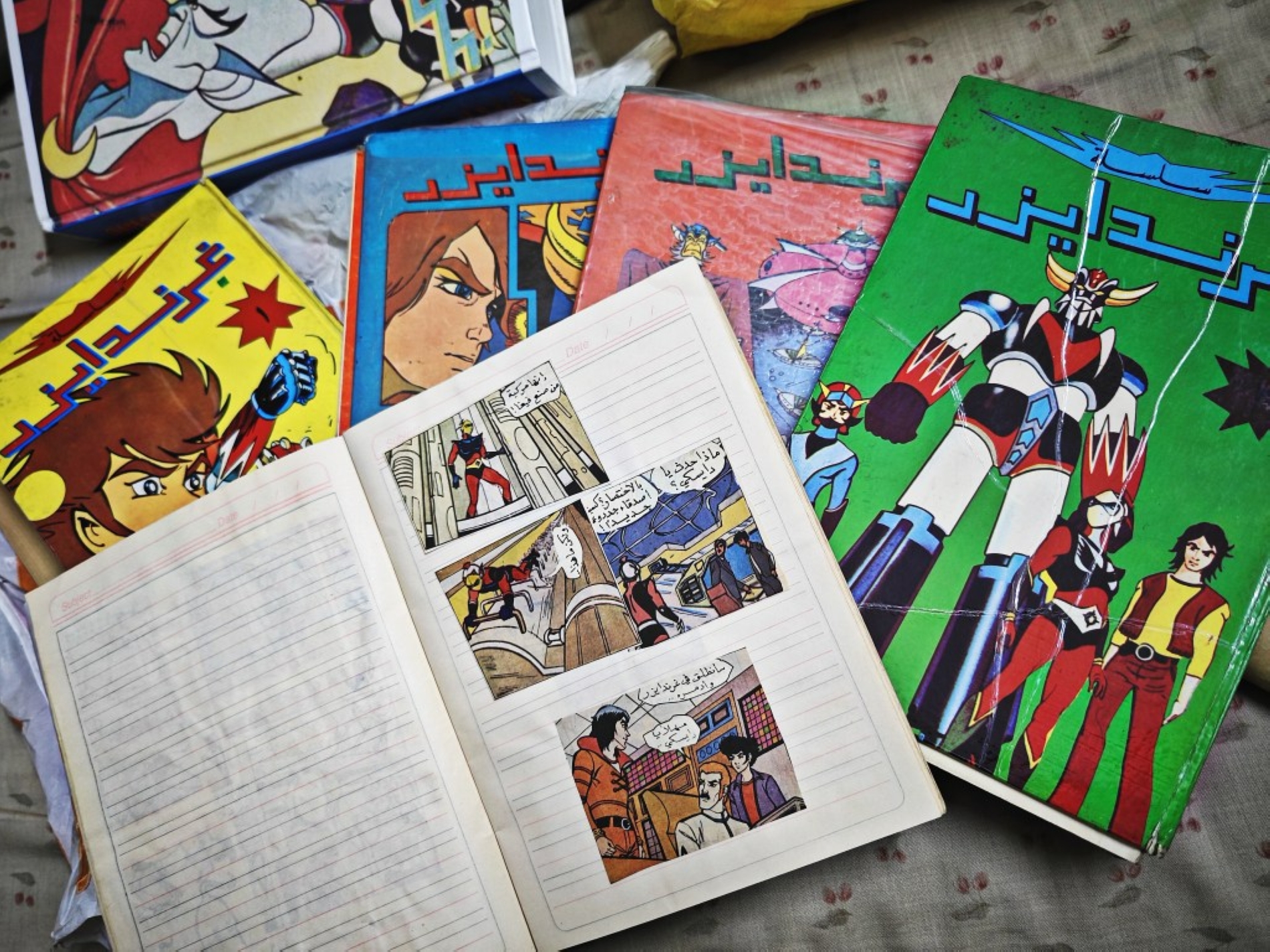

While the world celebrates Grendizer, the Arab world’s connection to the series remains uniquely intimate. No other animated show has achieved the same level of fame, resonance, and longevity. Grendizer became a vessel for symbolic narratives—of the Arab-Israeli conflict, of Arab identity, of the defence of the Arabic language, and of the universal struggles for freedom and justice.

Its original broadcast on Lebanon’s state television was a unifying cultural moment, one that continues to evoke a deep and abiding nostalgia. The show’s enduring relevance has prompted major Arab platforms, including Shahid, to reintroduce it to new audiences, many of whom had never encountered it before. In doing so, Grendizer has become a meeting point for generations, a shared cultural touchstone whose echoes still reverberate in the present.

Palestinian and Arab symbolism

Grendizer’s Arabic incarnation emerged in the late 1970s, at a time when Lebanon was engulfed in civil war and grappling with Israeli occupation. The Palestinian cause, in that moment, was not merely a political issue; it was a visceral, emotional, and cultural touchstone for many Lebanese and Arabs. Its presence extended beyond armed struggle, permeating fierce cultural battles over identity, language, and resistance.

In this charged atmosphere, the decision to dub Grendizer into Arabic was not incidental. It was a deliberate act of symbolic alignment with the Palestinian narrative, entrusted to a trio of Palestinian figures whose lives were steeped in activism and cultural production. Operating under the banner of the Union of Arab Artists, these men—Abdel Majid Abu Laban, the folk poet Abdullah Haddad, and the intellectual Subhi Abu Lughod—became known as ‘The Three Musketeers,’ or ‘The Three Palestinian Musketeers’.

Their choice of voice actors reflected the same symbolic intent. Chief among them was Jihad Al-Atrash, cast as Duke Fleed. Already known to Arab audiences for his dignified roles in historical dramas, Al-Atrash embodied the gravitas and moral clarity that the Arabic adaptation sought to project.