The United States is once again embroiled in a spirited debate surrounding the potential revaluation of its massive gold reserves, with advocates arguing that it could help alleviate the nation’s substantial debt and restore confidence in the dollar. Beyond that, they believe it could pave the way for recalibrating the global monetary order and repositioning American financial leadership.

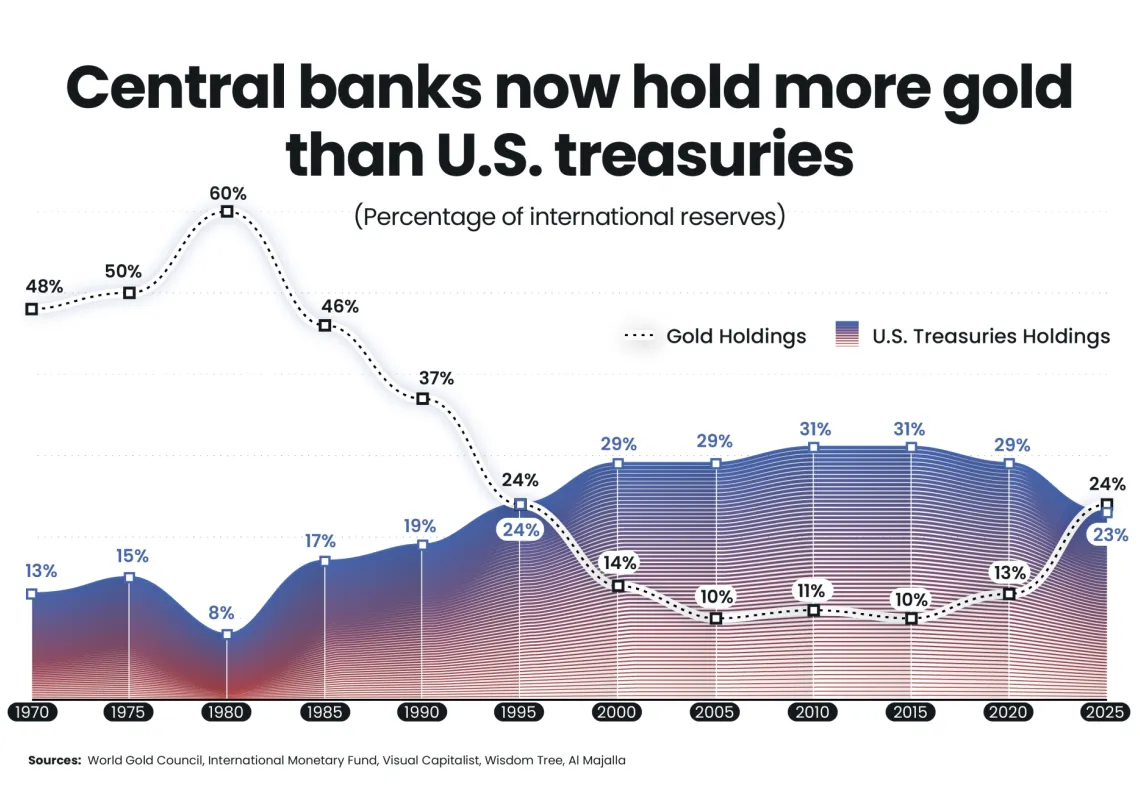

This renewed interest in gold stems from a convergence of critical developments, not least gold prices having soared to historic highs, with central banks across the world acquiring it at an accelerated pace. The other big factor is the US national debt having now surpassed $38tn, with little indication of retreat. Against this backdrop, revaluing gold is being floated as a potential fiscal lifeline. Proponents see it as a way to raise capital without increasing taxes or issuing new debt.

Forgotten treasury

The roots of America’s gold holdings lie in the Gold Reserve Act of 1934, introduced under President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The act followed Executive Order 6102, through which the federal government seized monetary gold from private citizens in exchange for compensation based on the official price of $20.67 per troy ounce.

Following this, the Treasury and financial institutions were barred from redeeming dollars for gold. A portion of the confiscated bullion was placed under the care of the Federal Reserve and stored at Fort Knox in Kentucky, now seen as a symbol of latent national wealth. Additional reserves were secured within the vaults of Federal Reserve Banks in New York, Denver, and West Point.

A year after the initial confiscation, a second revaluation lifted the official gold price to $35 per ounce. This adjustment increased the Treasury’s gold-backed wealth by 69%, while also devaluing the dollar by around 41% in relation to gold. In the early 1970s, President Richard Nixon oversaw a third revaluation, fixing the official gold price at $42.22 per ounce.

That figure has remained unchanged in the Treasury’s accounts for over five decades, despite the steep rise in market prices on the global stage. The result is a significant accounting discrepancy that leaves one of the United States’ most concrete financial assets severely undervalued in official records. This distortion continues to cloud the true fiscal potential embedded within the nation’s gold reserves.

Strategic instrument

According to the Federal Reserve, the US Treasury holds 261.5 million ounces of gold. Valued at just $11bn under the outdated pricing formula, this figure significantly understates the true worth of this vast reserve of 8,133.46 metric tonnes—the largest national stockpile in the world.

Interestingly, this could be revalued through a simple accounting measure, and such an adjustment would not require congressional approval. Under the authority granted by the Gold Reserve Act of 1934, the President can revise the valuation to reflect current market conditions.

These could be drawn from benchmarks such as the London Bullion Market, the COMEX exchange, or a higher value determined by the President. The resulting accounting gains, potentially worth hundreds of billions or even trillions of dollars, would be credited to the Treasury in a dedicated account at the Federal Reserve. This would immediately strengthen the government’s fiscal position.