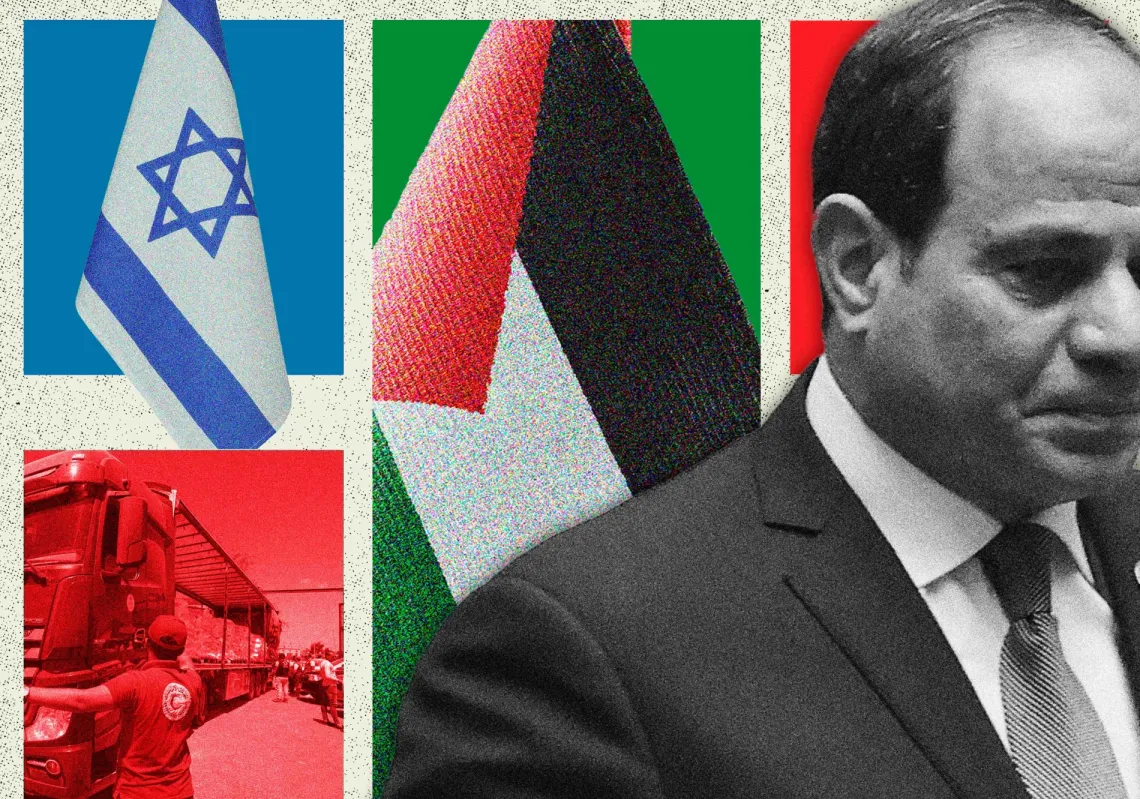

It seems likely that Egypt will be given command of the international stabilisation force being envisaged for the Gaza Strip as part of Phase II of US President Donald Trump’s peace plan. For Cairo, this is less an honour than a bitter medicine.

The force is likely to include troops from other states, not least from Islamic and Arab nations, to address a series of security, economic and geopolitical concerns. Backed by the US, Europe, and with a proposed UN Security Council mandate, the 5,000-strong force will aid post-war reconstruction efforts following the Israel-Hamas ceasefire reached earlier this month.

Its responsibility will include overseeing security when (and if) the Israeli army withdraws. It also includes disarming Gaza-based militant groups like Hamas, and securing a transitional Palestinian government, the formation of which is still being contested (Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has ruled out Palestinian Authority involvement in post-war Gaza).

In Jerusalem on 21 October, the Egyptian intelligence chief met US Vice President JD Vance and US Middle East Envoy Steve Witkoff (together with Trump’s son-in-law Jared Kushner) to discuss the fast-approaching 'day after’.

Egypt is well aware off the difficulties of the role ahead, which carries security, political, economic, and social risks. Gaza’s volatile history and pending security vacuum, together with Egypt’s domestic vulnerabilities and strained regional dynamics, only add to an already-noxious mix.

Egyptian troops, who will make up most of this international stabilisation force, could easily be drawn into indefinite operations against Gaza-based militants, including the remnants of Hamas or emerging factions and gangs. Sky News, Israeli newspaper Ha’aretz, and other media outlets have already reported that Israeli forces are supplying some anti-Hamas armed groups in Gaza.

Symptoms of the post-war turmoil are already appearing, with Hamas settling scores with Gaza residents and families believed to have spied for Israel during the war. In Rafah on 19 October, Hamas fought running battles with one such group believed to be led by Yasser Abu Shabab. The head of a former looting gang, he reportedly gets cash, guns, and cars from Israel, supplied via crossings.

In this context, Gaza’s security vacuum is only likely to widen—especially if Hamas does fully disarm—as it is bound to do according to the ceasefire agreement. If not, it could adopt a Hezbollah-like model, remaining as an armed force in the shadows without directly ruling Gaza.