On 17 February 1945, a Syrian-British summit was arranged in Cairo by King Farouk and King Abdul-Aziz al-Saud of Saudi Arabia. Syrian President Shukri al-Quwatli asked British Prime Minister Winston Churchill to invite his country to join the United Nations, due to be launched in San Francisco next April.

Syria, at the time, was still under the tutelage of colonial France and was thus barred from entering the League of Nations, which predated the UN. And it was the League of Nations that had famously approved the French Mandate on Syria back in the early 1920s. Churchill said that only countries that had contributed to the Allied war effort could join the UN, prompting al-Quwatli to declare war on Nazi Germany on 27 February 1946. A few days later, an official invitation was extended for Syria to attend the San Francisco Conference.

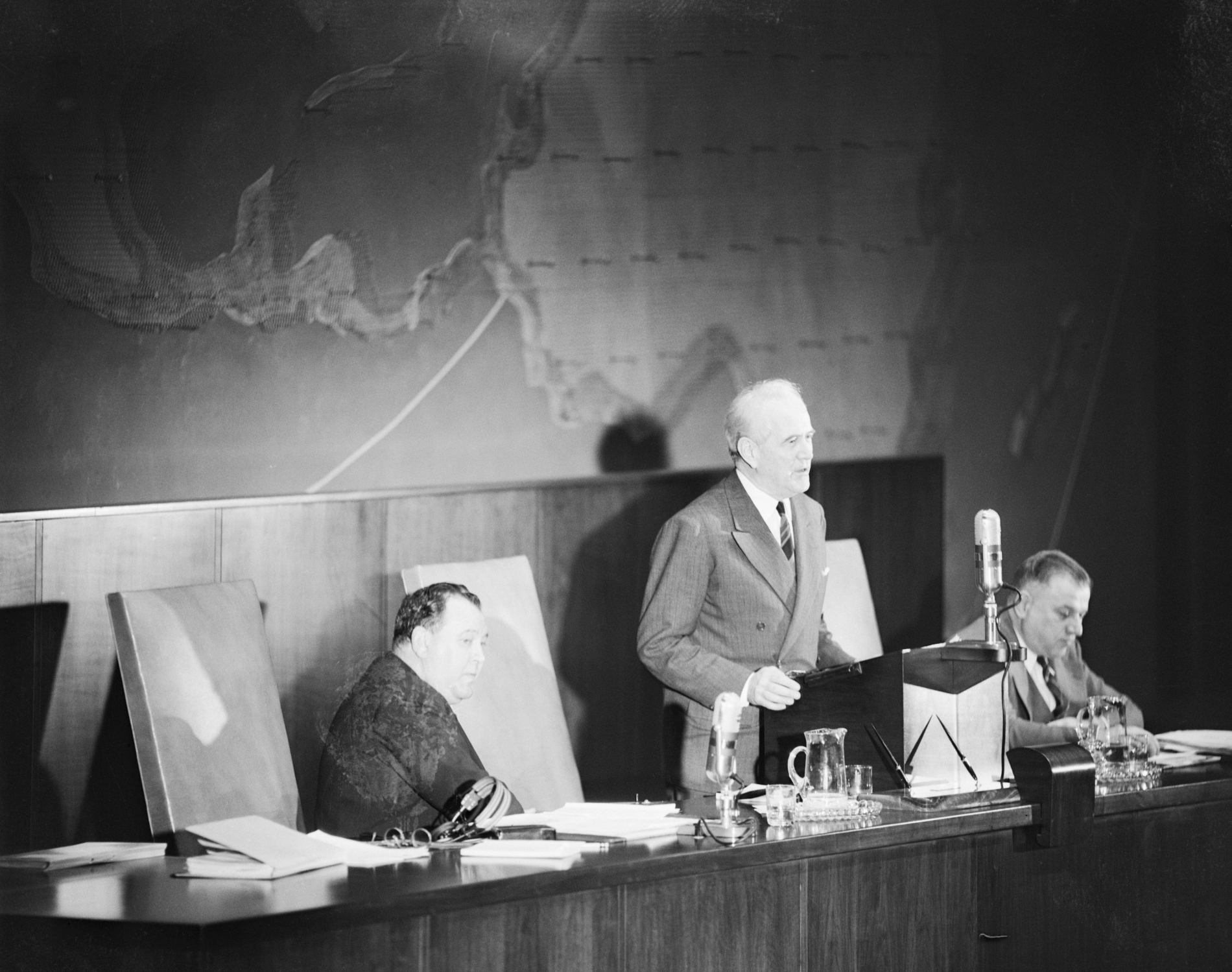

Prime Minister Fares al-Khoury was appointed head of the Syrian delegation; a brilliant legal mind and graduate of the American University of Beirut (AUB), he was also one of the founding fathers of modern Syria. Al-Khoury carefully selected his delegation—all fellow AUB alumni like Dr Farid Zeineddine, Dr Constantine Zurayk, and Syria’s envoy to Washington, Dr Nazim al-Qudsi. In his memoirs, al-Khoury described signing the UN Charter as the happiest day of his life, given the great hopes pinned on the international organisation to amplify the voice of oppressed nations.

Al-Khoury met US President Harry Truman, who delivered the opening address, and, beyond signing the Charter (with Zeineddine serving on the drafting committee), he joined the legal committee that approved the UN’s blue flag. The committee included Sir Hartley Shawcross (UK), Dr Walid Rafat (Egypt), UN Legal Affairs Assistant Secretary-General Ivan Kerno, and Deputy Secretary-General Andrew Cordier.

Syria’s independence

Al-Khoury was still at the UN when French forces attacked Damascus on 29 May 1945, seizing the moment to condemn France and expose all crimes committed in Syria since the start of the occupation back in 1920. Churchill intervened to halt the aggression on 1 June 1945, summoning the French Foreign Minister to London to negotiate a military withdrawal from both Syria and Lebanon.

For their part, the French demanded retaining troops in Lebanon to safeguard their Middle East interests, as stipulated in Paragraph 5 of the Anglo-French London Agreement. Paragraph 6 outlined that the British and French governments would subsequently inform Syria and Lebanon of the terms agreed upon in London and invite them to subsequent talks.

Along with his Lebanese counterpart Bechara El Khoury, al-Quwatli flatly rejected the London Agreement, saying that Syria and Lebanon had been excluded from negotiations regarding their future. They argued that both were now sovereign countries, citing Allied proclamations. Al-Quwatli even proposed addressing the UN in person, but France blocked the suggestion, prompting a joint Syrian-Lebanese memo demanding the agreement’s annulment.

Matters reached the Security Council in London on 14 February 1946. That same day, Fares al-Khoury met British Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin, accompanied by Lebanon’s envoy Camille Chamoun, who was joined the next day by Foreign Minister Hamid Frangieh. Both delegations demanded unconditional withdrawal of French troops.

Aware of the unworkability of the 13 December 1945 accord, the British Foreign Office agreed to full evacuation and pledged to inform France. The UN oversaw the military withdrawal, with technical talks in Paris, setting a deadline of 30 April 1946. The French evacuation concluded by mid-April, however, and Syria celebrated its first Independence Day on 17 April 1946.

Opposition to Palestine partition

At year’s end, Syria was elected to replace Egypt as a non-permanent member of the Security Council, with 45 out of 53 votes. Fares al-Khoury, then 74, became Council president, presiding over two sessions in August 1947 and June 1948. His tenure coincided with Britain’s proposal to partition Palestine, mirroring its division of India in August 1947, which created modern Pakistan.

On 26 September 1947, Britain announced its impending withdrawal from Palestine by May 1948, triggering the UN Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP)—an 11-member body excluding major powers, Arab states, and Jewish representatives. Al-Khoury forwarded Soviet envoy Andrei Gromyko’s pro-Zionist speech to Damascus and noted Iranian delegate Nasrollah Entezam’s Arab sympathies, while warning of Swedish judge Emil Sandström’s ties to the Jewish Agency.

UNSCOP’s Middle East inspection tour included Jewish delegate Abba Eban, while the Arab group appointed Camille Chamoun. Seeking re-election that year, President Truman voiced support for Jewish emigration to Palestine, aligning with the Soviet stance. After five weeks in Palestine, UNSCOP published its report on 31 August 1947.

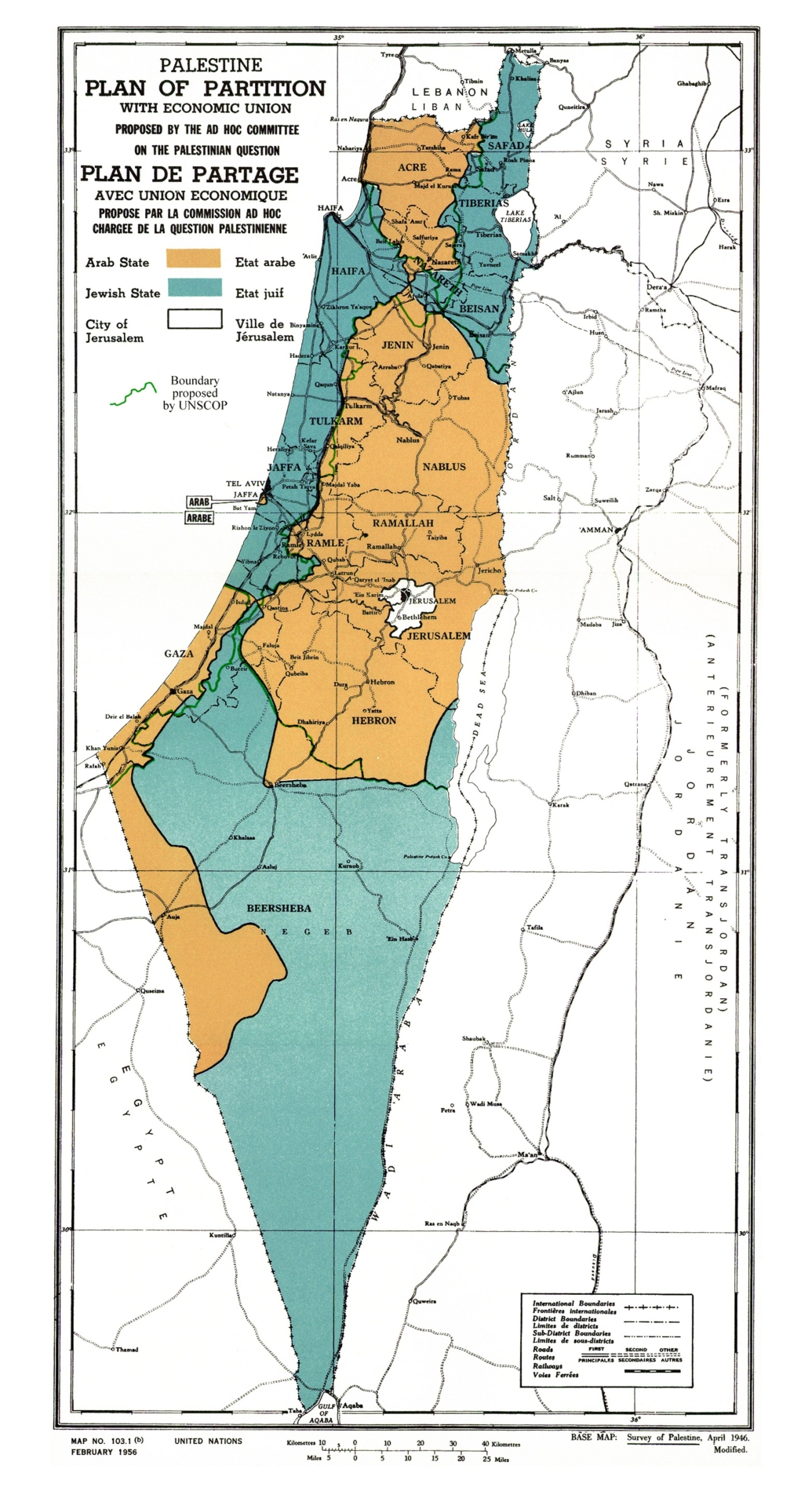

The UN debated it on 3 September, with Canada, Czechoslovakia, Guatemala, the Netherlands, Peru, Sweden, and Uruguay endorsing two separate states (Arab and Jewish), while India, Iran, and Yugoslavia advocated one state under international trusteeship for Jerusalem. Australia abstained. The General Assembly adopted the Partition Plan on 29 November 1947, granting Arabs most of the highlands and a third of the coastline, while allocating Haifa, Marj ibn Amer, Eastern Galilee, the Negev, and Umm Rashrash (55% of Palestine) to the Jewish state.

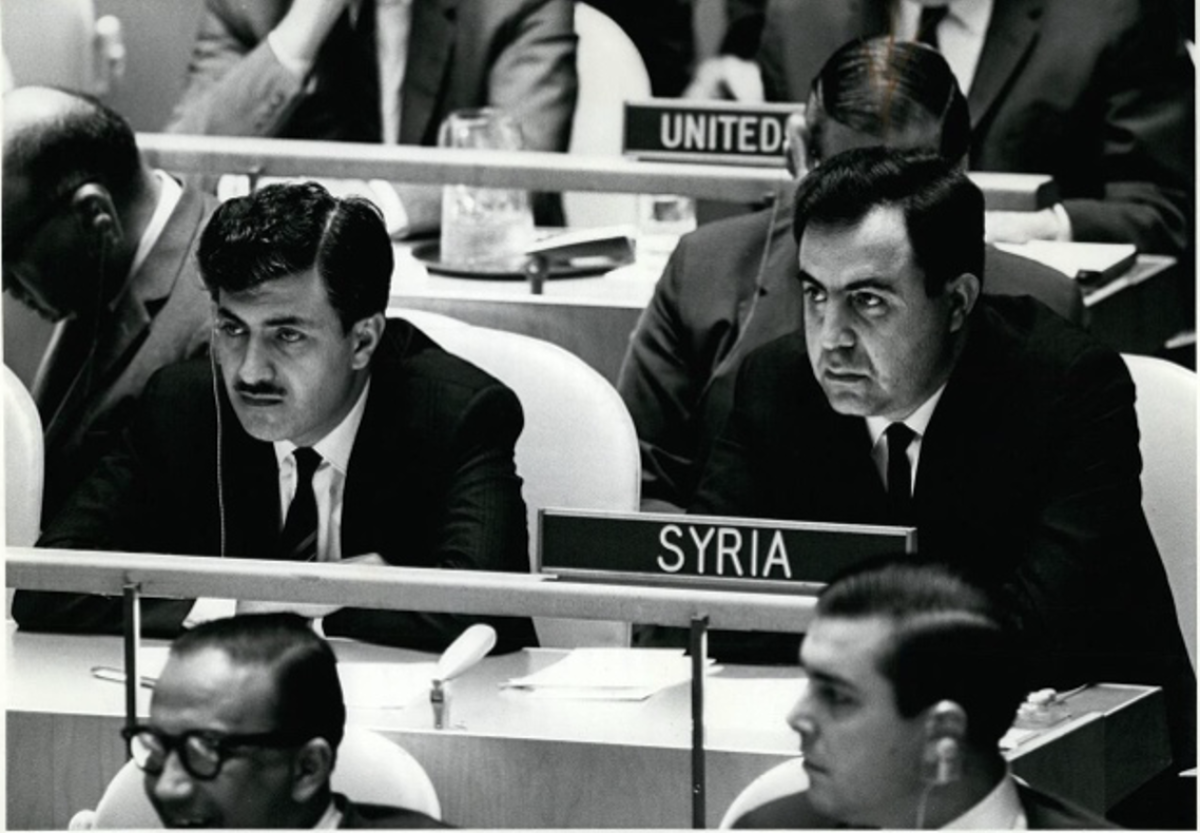

The Syrian delegation vehemently opposed partition, boycotting the vote alongside Arab delegations. Al-Khoury continued his work, and Syria’s UN role expanded in the 1950s, including membership in the Commission on the Status of Women, where Syrian adviser Alice Qandalaft served as rapporteur (1951–52).

Syria purchased a permanent home for its New York ambassador, formerly Richard Nixon’s home (just as its DC embassy was William Howard Taft’s residence). On 20 June 1955, Foreign Minister Khaled al-Azm delivered Syria’s speech at the UN’s 10th anniversary. When he mentioned Algeria’s liberation, the Dutch chair interrupted him.

Al-Azm recalled in his memoirs: "The gavel banged... I paused and turned to the Chairman, who said: ‘Be mindful, Mr Speaker, of topics that stir discord.’ My limited English left me no retort but a dismissive wave before I resumed." He added: "By God, the audacity of this man—silent yesterday as Soviet Foreign Minister Molotov lambasted the US—to chastise a small nation’s representative!"