"In my naivety, I believed that the union between the states of Damascus and Aleppo was a momentous historical event for Syria. So I rushed to the government Serail to record the events of that happy day for future Syrian generations. Imagine my profound astonishment when I reached Marjah Square, where I found the people of Damascus entirely unconcerned, passing through the streets as indifferent bystanders, as if all of this did not concern them."

With these words, French journalist Alice Poulleau describes her observations in Damascus on 1 January 1925, when the Damascus State merged with the Aleppo State to form what the French called Etat du Syrie (State of Syria). After five years of fragmentation and semi-autonomy, this merger put an end to the mini-state system that the French had imposed when occupying Syria back in 1920.

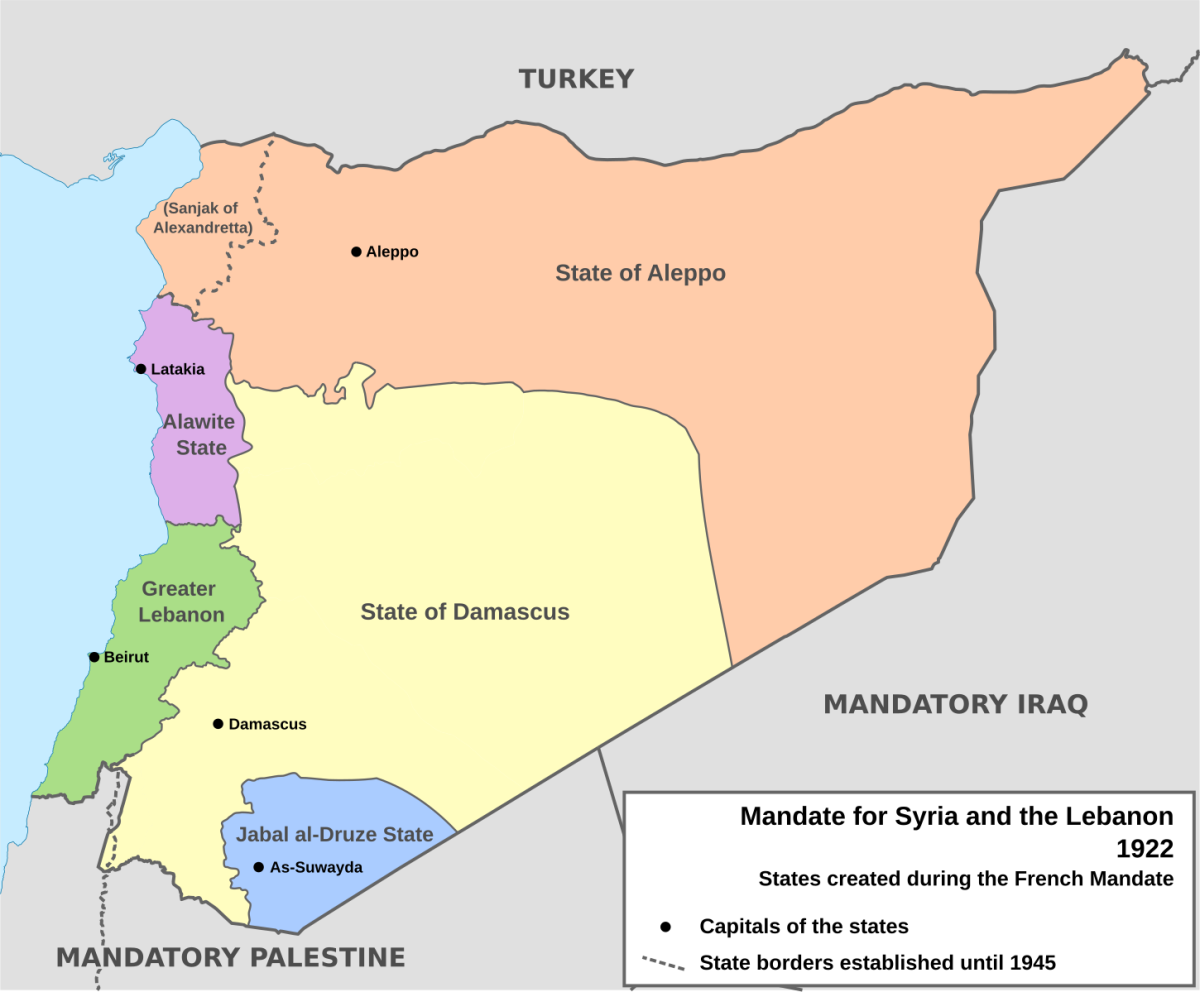

Colonial France had initially divided Syria and would later merge the mini-states into the Syrian Federation, or the Itihad al-Duwal al-Souriyya (Syrian Union), on 29 June 1922. When the federal experiment failed, it was swiftly dismantled by the French and replaced by the Syrian State in 1925—the entity that Poulleau references in her journal.

Borders of these mini-states were drawn on maps, without physical barriers separating them in reality. Each adopted its own flag and independent administrative system, and only two had local rulers (Haqqi al-Azm in Damascus and Kamil Pasha al-Qudsi in Aleppo). Both the Alawite and Druze states were placed under direct French military control.

The State of Damascus included the cities of Homs and Hama, while the Druze State encompassed the entire Houran province and the strategic cities of Daraa and Sweida. Authority of the State of Aleppo extended to the Euphrates River as far as Deir ez-Zor, while that of the Alawite State reached Latakia, Tartus, and Masyaf.

According to French statistics, the population of the State of Damascus stood at 600,000: 75% Sunni Muslims and 11.3% Christians, along with a 10,000-strong mix of Shiites, Jews, Alawites, and Druze, plus 49,000 foreigners (mostly French citizens or soldiers from France’s North African colonies).

Damascus grievances

The Damascus State was given a blue flag with a white circle at its centre and a small French flag in the upper left corner. Damascene anger did not stem from separating their city from Aleppo, but because the capital of the federal project was Aleppo rather than Damascus, and its president, Subhi Barakat, was a northerner from Antioch, and not a native of Damascus.

Subhi Barakat tried appeasing the Damascenes by appointing Sami Pasha Mardam Bey as his deputy, but this didn't satisfy them. Adding insult to injury, the people of Damascus were deeply concerned about detaching their state from Palestine and Lebanon—specifically from the port of Beirut—and imposing customs tariffs on goods exported from Damascus to these two countries. Beirut at the time was considered the port of Damascus; all the city’s trade and industry was exported through it before the establishment of Latakia Port in the early 1950s.

Suddenly, Beirut became an independent city separated from Damascus by land borders, and goods exported to Tiberias, Jaffa, Nablus, and Jerusalem were now required to pay customs duties shared by the French and British. The Damascus Chamber of Commerce submitted a brief to the French High Commissioner challenging the customs tariffs imposed on goods exported to Palestine and Lebanon, stating: "No fewer than 25,000 Damascene families working in industry and trade with Palestine contribute 3mn golden Ottoman liras to the state treasury per year." The brief added that most of them would now become unemployed due to the customs duties and borders imposed by the Mandate authority.

Aleppo grievances

Conversely, Aleppo was no more satisfied with the federalism than Damascus, despite being the wealthiest of the three mini-states and hosting the capital. While Damascenes’ anger resulted from borders with Palestine and Lebanon, Aleppine anger was because borders suddenly emerged with Türkiye, severely damaging Aleppo’s thriving industries there.

The population of the Aleppo State was 604,000: 520,000 Sunni Muslims, 52,000 Christians, 7,000 Jews, and 3,000 foreigners. It was assigned a white flag adorned with three stars and a French flag on its left edge.

The main problem of the Aleppo State lay in its own wealth, with the French deducting 1.2mn French francs from its coffers to finance the impoverished Alawite State during its first year. The Union made it obligatory for each of the three states to channel 50% of its revenue to the state treasury, which would then be distributed according to the specific needs of each of the three states.