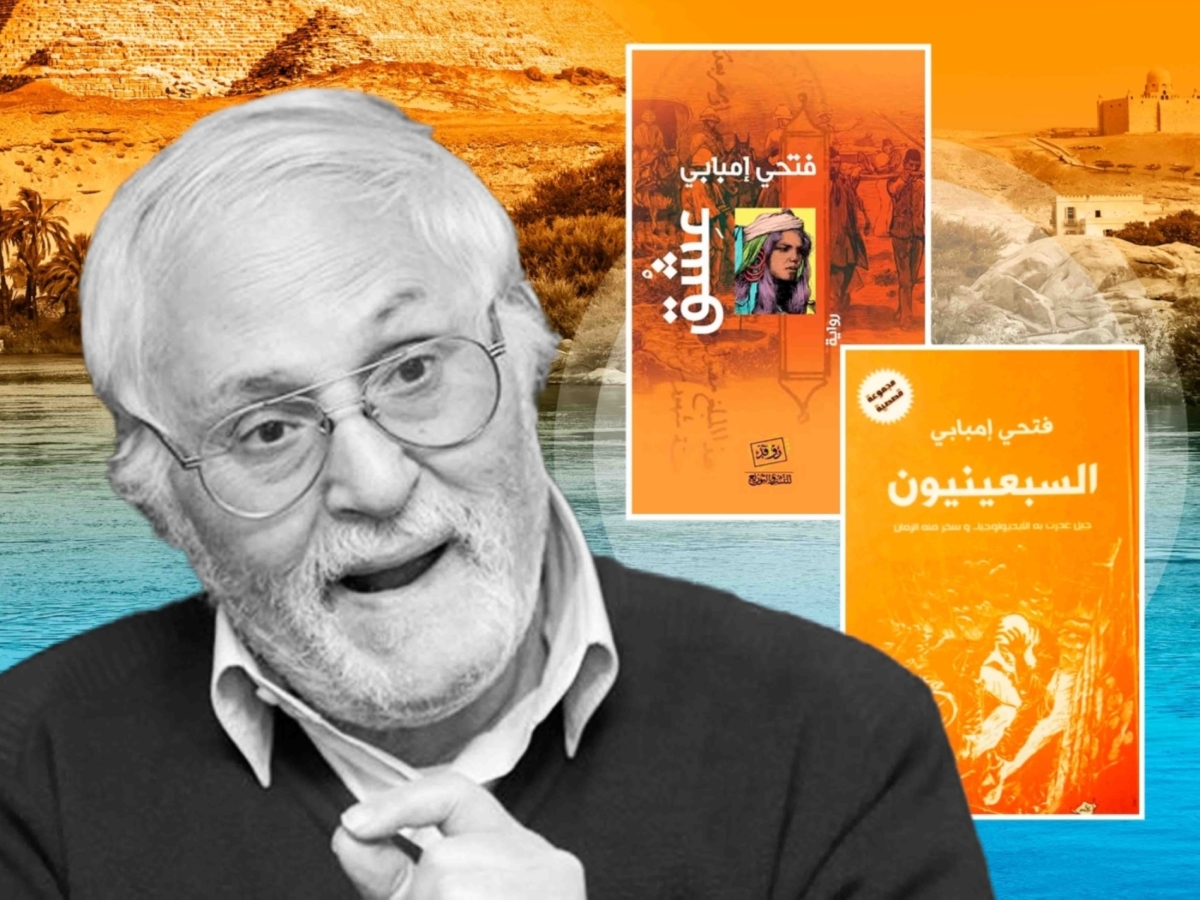

The Egyptian historical novelist Fathy Embaby is one of the most compelling voices in contemporary Arab literature, and he has recently published the fourth part of his renowned River Quintet.

Passion is a tribute to the thousands of officers and soldiers, both Egyptian and Sudanese, who fought in the Equatoria Province in the Upper Nile against slave traders and religious fundamentalists.

It underlines Embaby’s reputation for confronting reality head-on, extracting its tragedies and re‑shaping them into texts that delve deeply into the human condition and uncover the unspoken in history, politics, and society.

The prolific and award-winning writer, born in 1949 and a civil engineer, spoke to Al Majalla about what writing means to him, where he outlined his method in chronicling a troubled period in Arab history, and spoke out about Egypt’s retreat from parts of the Nile valley.

This is the conversation.

What is writing to you?

Writing is a creative human act—a divine gift that cannot be quantified. It is a fusion of passion, pleasure, suffering, sorrow, joy, and happiness. When I write, I address, firstly, the individual and collective consciousness of the Egyptian and Arab community with the aim of broadening perspectives and tackling the dilemmas of individual and collective identity.

Tell us about your newest novel, Passion, the fourth part of your River series. What sets it apart from the earlier volumes?

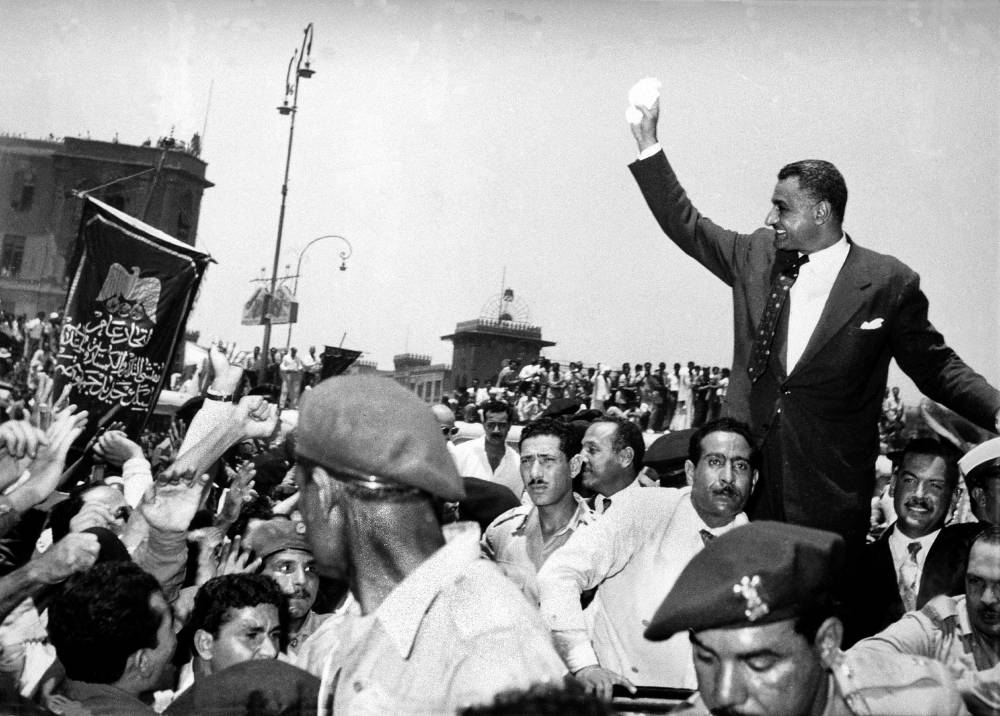

In 1883, a bloody battle took place in the Shikan forest, south of the city of Al‑Ubayyid, the capital of Kordofan in central Sudan, between the Mahdist army under the leadership of the Mahdi and the Egyptian government forces commanded by British Colonel William Hicks, in which the Mahdist forces killed 13,000 Egyptian and Sudanese officers and soldiers.

By early 1885, the Ansar and Mahdist forces had entered Khartoum and seized control of central Sudan, effectively isolating the Egyptian forces stationed in Equatoria Province (present-day South Sudan) from their bases in Cairo.

At that time, the Egyptian presence in Equatoria numbered some 60,000 officers, soldiers, civilian employees and their families—Egyptians and Sudanese, Arabs and Africans, Muslims, Copts and pagans.

For a decade, they faced formidable trials: rebellion by the hostile Dinka, the seizure of Egyptian weapons, provisions, and ammunition, battles against Mahdist-aligned slave gangs, and uprisings by local tribes.

Yet their gravest ordeal came when the Egyptian government, under the treacherous Khedive and Prime Minister Nubar Pasha, abandoned them, leaving them exposed to the ambitions of British imperialism and the relentless advance of the Mahdist forces.

Caught between foreign neglect and domestic betrayal, a coalition of young Egyptians and Sudanese officers formed a military council to defy the prevailing circumstances.

They rejected evacuation, refused to relinquish Equatoria, and strove to thwart the machinations of opportunistic foreign powers eager to exploit the vacuum, along with every design aimed at severing Egypt from Sudan and breaking the unity between the north and south of the Nile Valley.

Describe the research process in writing this novel.

In the Gates of Heaven instalment, I included an appendix listing more than 40 references, books and studies across various fields of knowledge, historical sources, dozens of maps and references related to the Nile, and to Sudan, Egypt, Uganda, northern Congo, and others.

Writing a novel is an extremely arduous endeavour that demands dedication and persistence. Finishing the work is a sublime feeling filled with joy and fulfilment.