In the lap of a pine-covered mountain, just below the town of Ras el-Metn in Mount Lebanon, lies the museum of the late Lebanese artist Saloua Raouda Choucair. To get there, you have to travel across neglected, meandering roads—roads whose eroded asphalt is marked by pits and furrows. Along the edges, a wild urbanism has emerged: chaotic, aggressive, and itself seemingly neglected and redundant.

This short journey—less than an hour by car from Beirut—proved unexpectedly tiring as we wound our way up and down the valley of Lamartine, named after the French ‘Orientalist’ poet Alphonse de Lamartine, who fell under the spell of Lebanon in the 19th century.

Lamartine once described this valley as the most beautiful part of the country, long before it was struck by what now seems an incurable curse. In the 1980s, the valley bore witness to fierce battles during the Lebanese Civil War. The scars of that violence remain; neither the land nor its memory has truly healed.

As expats returned to Lebanon this summer, they did so against a grim backdrop of economic collapse, plummeting living standards, and deepening political, financial, and moral corruption. Amid such turmoil, Hala Choucair, daughter of the late artist and a painter herself, opened her mother’s museum to visitors.

With its refined, spectral architecture nestled amidst coniferous isolation, its air of calm elegance, and the quiet sophistication of its guests and collectors, the museum stands in stark contrast to the nauseating scenes of unchecked urban sprawl that assault the senses along the way.

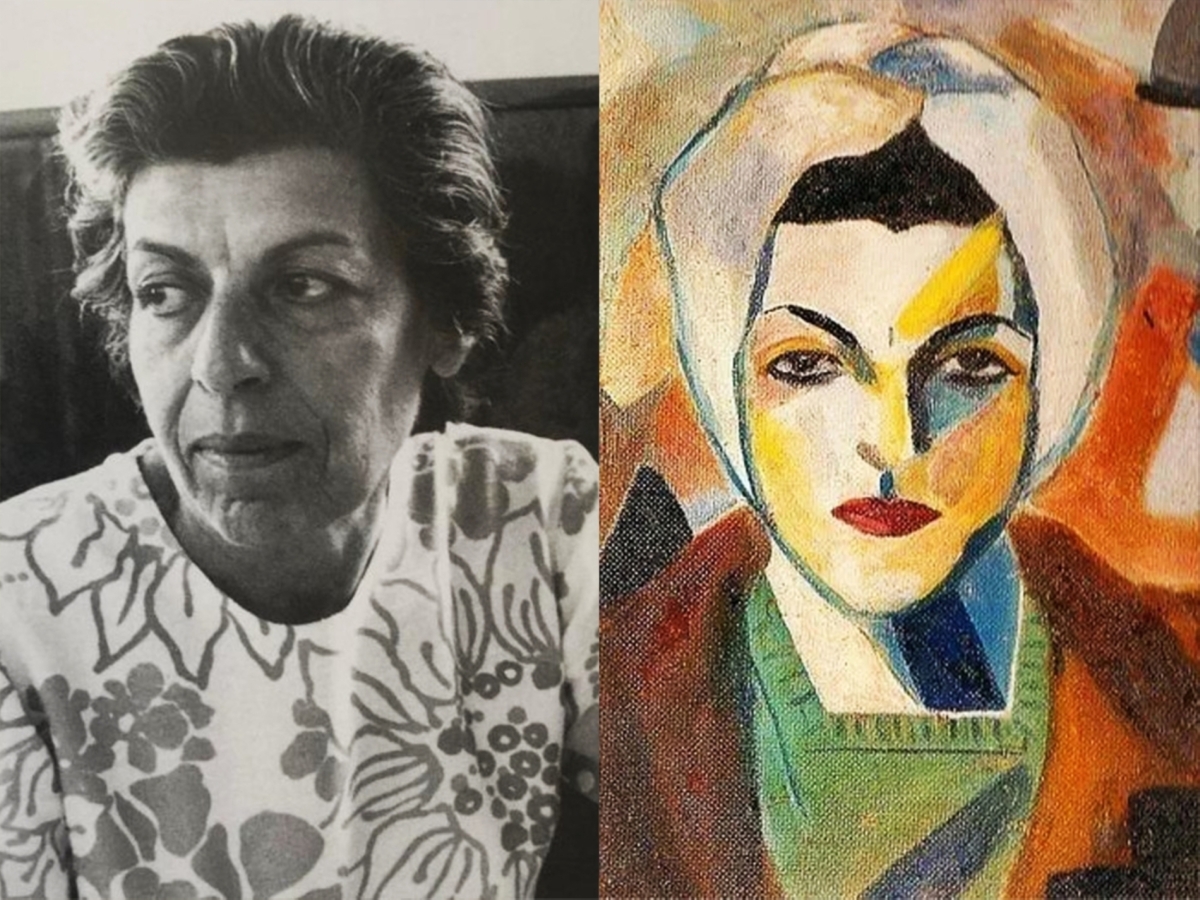

On arrival, visitors often felt the need to pause, seeking shelter in a shady spot in front of the museum, to rest and recover from the ‘bumps’ of the road. Only then could they enter the world of Saloua Raouda Choucair, exploring her abstract works and encountering the artist herself through her daughter’s reflections and writings. Collectively, these reveal Choucair’s role as a pioneer of modern abstract art in the Middle East.

Choucair lived a full century. Yet she never grew tired of life, work, or worry, remaining restless and alert until the end of her life. Her daughter remembered this enduring concern, describing a table her mother had designed, which she used in her Beirut home alongside a set of matching chairs.

A memory preserved

Today, the table and chairs are preserved in the museum, surrounded by a diverse array of artworks. Among them are pieces inspired by classical Arabic poetry—a lifelong love of Choucair’s. She engraved poetic verses in many of her wooden and metal sculptures under the title ‘Mathnawiyat’, evoking not only the literary tradition of Arabic verse but also the spiritual resonance of Jalal al-Din Rumi and his poetic Mathnawi.

Choucair's persistent worry stemmed from a forward-looking anxiety: that her artworks, designed across many genres and materials, would never find the uses or public settings she envisioned. Her art was meant not only to be seen but to be lived with: placed in homes, integrated into public spaces, part of daily life. She dreamed of her sculptures and designs enhancing the environment, transforming ordinary places, and subtly transmitting her refined aesthetic to casual passersby.

For Choucair, art was not a luxury or ornament; it was a public good, a tool for elevating the collective taste and lived experience of society. Her vision for art was functional, civic, and ethical—deeply connected to how people live and move through shared spaces.

But in Lebanon, as in much of the Arab world, things have unfolded in the opposite direction, especially since the mid-20th century. Public spaces have been destroyed, neglected, or stolen. What should have been sites of beauty and civility have instead become settings for violence, erasure, and decay. It is as if time itself has reversed course: from familiarity to estrangement, from urbanity to barbarism, from a rooted civic life to a state of wandering displacement.

The late Ghassan Tueni once called the 20th century in Lebanon and the Arab world "a century for nothing." That century began with promises of renaissance, enlightenment, education, social reform, and political freedom. But by the century's end, those promises had been broken, even weaponised. What once inspired hope has instead led to collapse, betrayal, and a lingering sense of loss.

Choucair's artistic and intellectual vision led her to explore the full spectrum of 20th-century visual and applied arts. She professionalised and produced work across diverse fields: beginning with painting—which she soon abandoned for sculpture—then moving into engineering-inspired forms, architectural design, traditional crafts (which she sought to modernise), and the design of fashion, furniture, carpets, household objects, and ornaments. Her artistic practice often approached what we now call installation or interdisciplinary art—materially abstract and genre-defying.