The story of the Syrian army’s entry into Lebanon remains a subject of controversy, even two decades after it withdrew in 2005. It is significant because it marked the beginning of what later became known as the era of “tutelage” over Lebanon.

Former President Hafez al-Assad initially deployed Syrian troops under the guise of the Palestinian Liberation Army, before officially committing them in early June 1976. Their crossing of the border coincided with the arrival of Soviet Prime Minister Alexei Kosygin in Damascus. The United States approved, as conveyed in a message to al-Assad via Jordan’s King Hussein. It also had tacit acceptance from Israel, which sought to diminish the influence of Yasser Arafat’s Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO), which was later expelled from Lebanon, relocating to Tunisia.

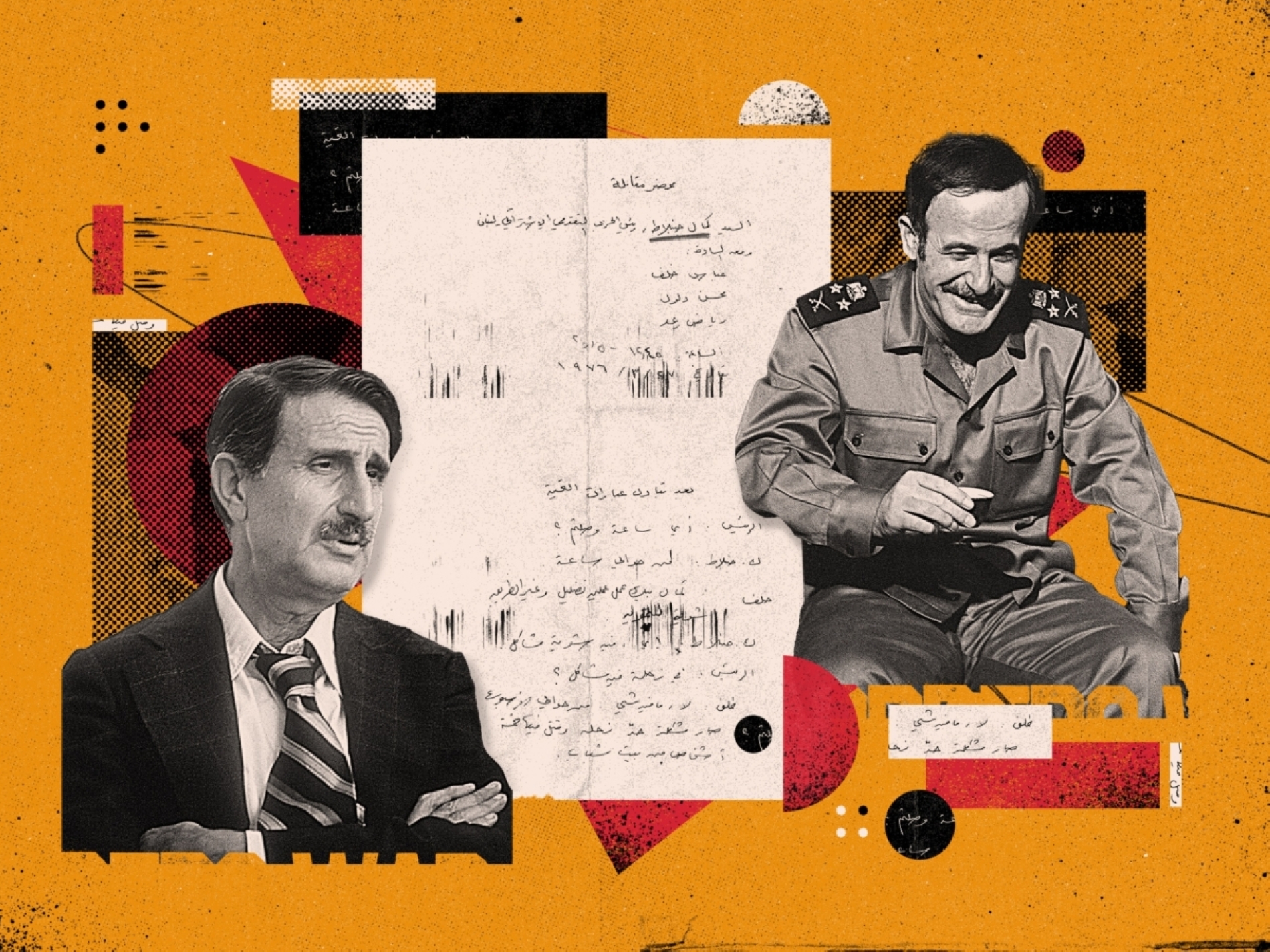

These insights are drawn from classified documents obtained by Al Majalla in the wake of the Assad regime’s collapse on 8 December 2024. They cast new light on the assassination of Druze leader and PLO ally Kamal Jumblatt in March 1977, nearly a year after his tempestuous seven-hour meeting with Hafez al-Assad in Damascus.

Jumblatt was a main opposition leader in Lebanon’s civil war, which had begun in 1975. By 1976, the opposition—aided by the PLO—controlled around 80% of Lebanon and was on the verge of military victory. His March 1976 meeting with al-Assad is significant because it was at this meeting that their divergent positions became clear.

The Assad-Jumblatt relationship remains one of the most enduring enigmas of the Lebanese civil war. Until now, it has been understood mostly through the oral accounts of those who worked with them, rather than through official documentation. The Assad regime had long pursued a policy of secrecy and denial in response to Arab accusations that Jumblatt was assassinated by Syrian intelligence.

This issue is still raw. Following the fall of the Assad regime last year, President Ahmed Al-Sharaa began his term by receiving Walid Jumblatt, the son of Kamal Bey and heir to the leadership of both the Druze community and Lebanon’s Progressive Socialist Party. In March, shortly after this meeting, authorities announced the arrest of Ibrahim Huwaija, the Syrian officer accused of orchestrating Kamal Jumblatt’s killing.

A region in turmoil

The seven-hour meeting between al-Assad and Jumblatt must be seen in context. The 1970s were marked by conflicts and shifts across the Arab world in the aftermath of the 1967 defeat to Israel and the events of Black September in 1970, which led to armed Palestinian groups being kicked out of Jordan, landing in Lebanon. Two months after Black September (a period of fighting between the PLO and Jordanian forces), al-Assad took power in Syria in November 1970.

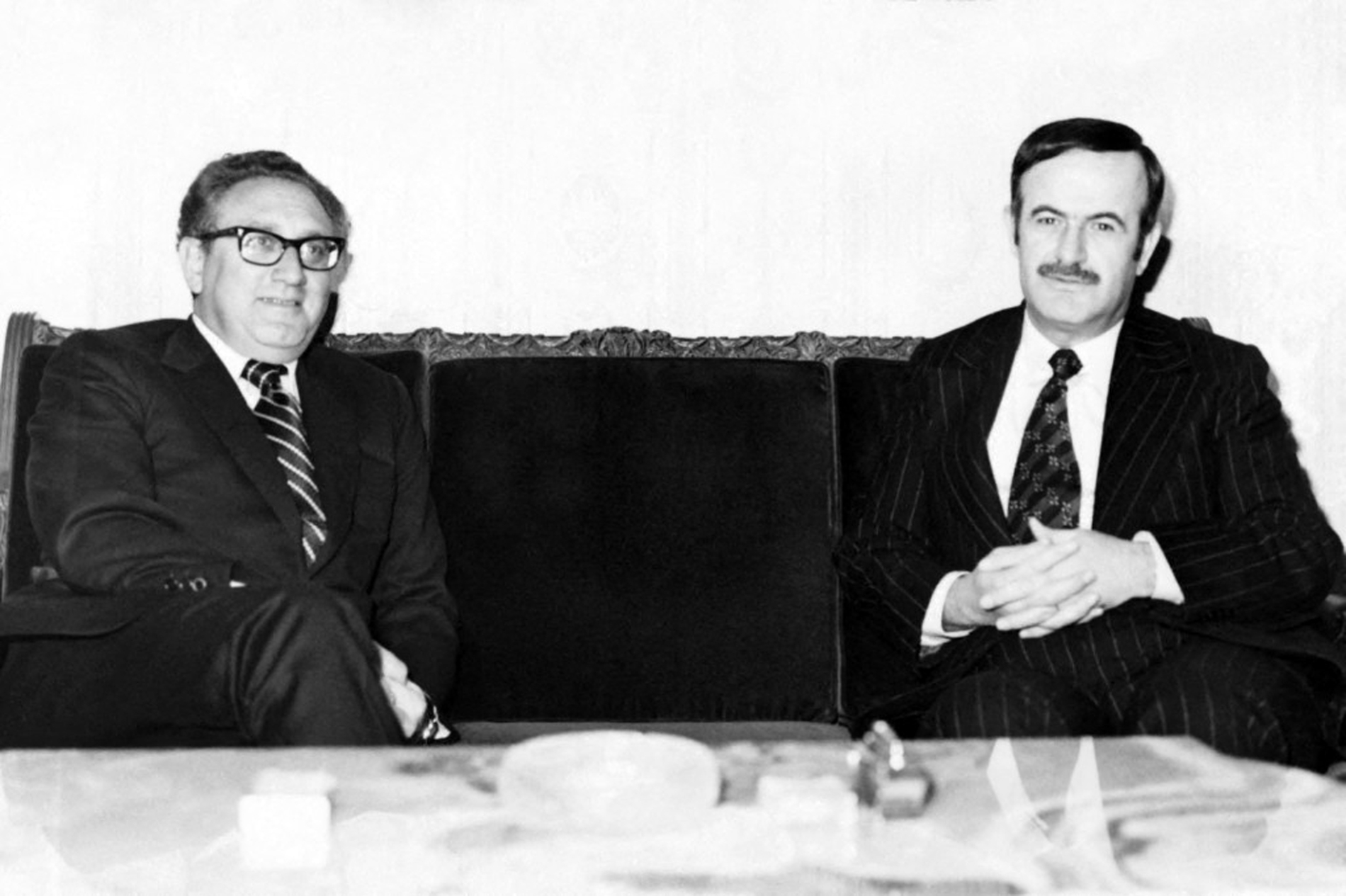

He signed a disengagement agreement with Israel in May 1974, just months after the October War of the previous year, securing the future of his political regime under an American umbrella provided by US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. Then the Lebanese civil war broke out.

In response, al-Assad strengthened his ties with various Lebanese political factions as a way of tightening his grip on Lebanon, which he considered to be Syria’s “soft underbelly.” Druze leader Kamal Jumblatt was a powerful figure in Lebanese politics. He had led the Progressive Socialist Party since 1949 and headed the Lebanese National Movement, which had, since 1969, united nationalist, leftist, and communist groups.

Al-Assad wanted international legitimacy for Syria’s intervention in Lebanon, drawing on its strategic alliance with the Soviet Union and functional relationship with the United States, while keeping Israel informed. In the early 1970s, Syria-US talks centred on restoring diplomatic ties following a period of rupture, and on the broader implications of Egypt-Israel negotiations that eventually led to the Camp David Accords.