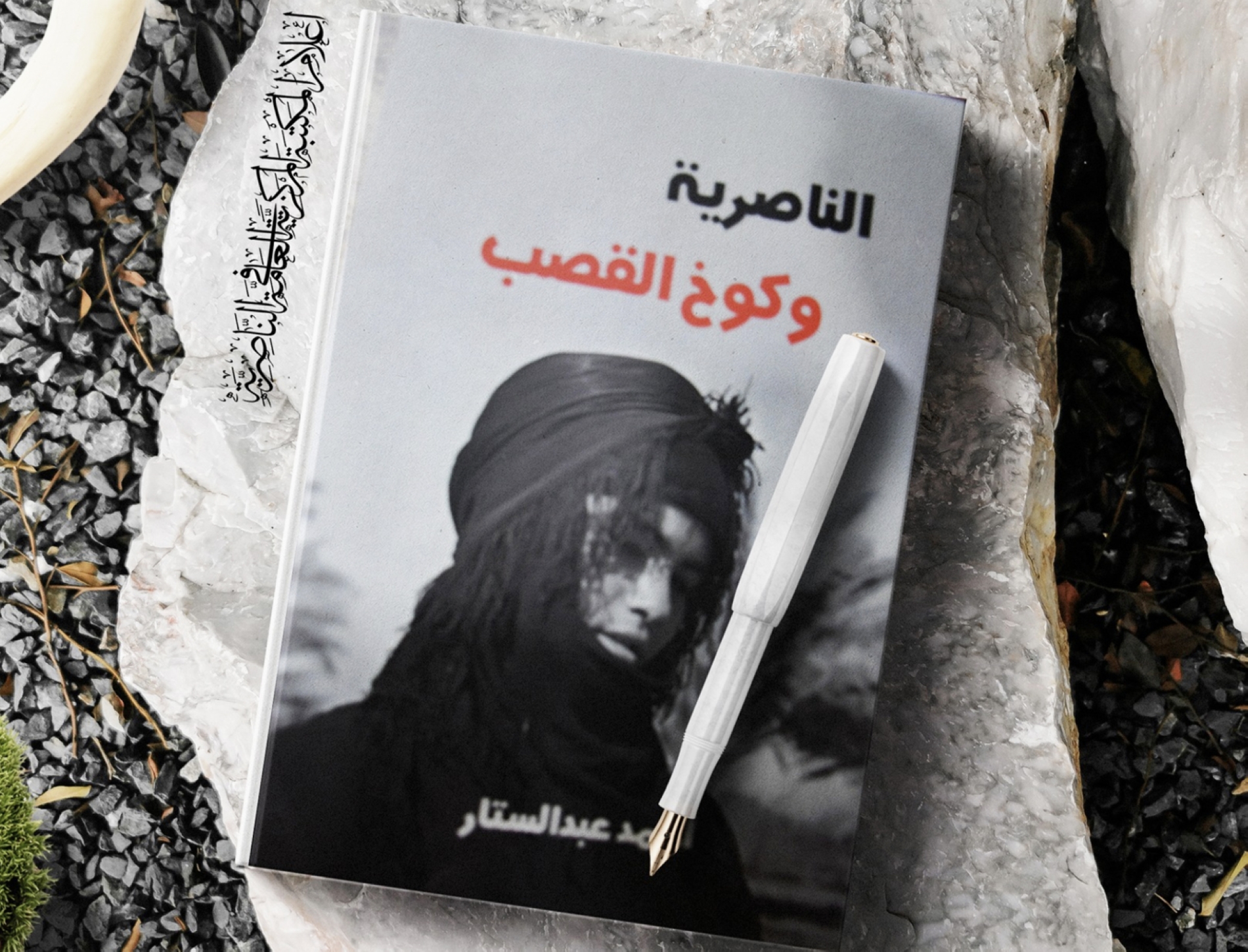

When construction of the city of Nasiriyah began in southern Iraq in the late 19th century, it inflicted a lasting wound. That wound—the fraught, tense relationship between city dwellers and rural folk—has been reopened by Ahmed Abdul Sattar without stylistic embellishment or academic detachment in Nasiriyah and the Reed Hut.

From the outset, Abdul Sattar declares that his allegiance lies with the question, not the answer. He begins with his own childhood, recalling the disdainful looks and the heavy-handed words with which the ‘civilised’ mocked the rural poor. So powerful were these impressions that, as he confesses, he himself adopted this outlook for a time, until broader and more complex experiences dismantled it.

The author does not seek to defend one group against another. Instead, he deconstructs pre-packaged assumptions. He argues that the contrast between countryside and city lies not in morality, but in modes of living. The rural population bears no inherent flaw, moral or otherwise. Instead, they come from a simpler social system, one more intimately tied to the land. The difference between the two is not a matter for condemnation, but for understanding. The rural person does not ‘corrupt’ the city. They simply do not speak its language. It is the city that chooses arrogance over attentiveness.

A shifting relationship

The author begins by dissecting the structure of the city of Nasiriyah, not as an urban entity, but as a social process. How did it come into being? Where did its class relations originate? Who were the first landowners? And how did tribal sheikhs evolve from protectors into instruments of exploitation?

In recounting this history, Abdul Sattar does not lean on nostalgia. Instead, he embraces what he terms the “historical materialist method,” one that links social relations to economic structures rather than ideological slogans.

The pivotal shift in his narrative emerges with the Ottoman decision to grant land ownership to tribal sheikhs. This move transformed the relationship between sheikh and peasant into one of landlord and tenant, ladened with taxes, exploitation, and humiliation. Thus began the migration, not as a choice, but as an inescapable fate. The rural migrant does not arrive in the city out of love for it, but in flight from the cruelties of the countryside. Yet in the city, he encounters a system that refuses to acknowledge his wounds.

This brings us to the moment of profound isolation. The peasant, in the city, alone, chases bread he does not know how to make, surrounded by glances that do not know how to forgive. The crime—as the author puts it—lies not with the peasant, but with the system that drove him to migrate, only to treat him as an outsider.

Given the scarcity of written records documenting such suffering, Abdul Sattar turns to oral history. He sits with witnesses—women and men who moved between the field and the pavement—and listens, then writes. Yet even here, many hesitate to reveal their names. The fear has not ended. Some recount their stories in a neutral tone; others break off mid-sentence, their voices faltering.

In one interview, the author asks a participant about the peasants. The reply is a lengthy account of the generosity of the sheikhs, as if the peasant never existed or as if speaking of him were somehow improper. In that moment, the author understands: marginalisation is not carried out by law or history alone. It also happens through silence, through indifference, through emotional complicity.

Unresolved guilt

Since childhood, there has always been something unsettling about the invisible divide between city and countryside, as if an unresolved guilt or a lineage of inherited hatred runs through traditions and dialects alike. In Nasiriyah and the Reed Hut, Abdul Sattar revisits this lingering anxiety, reshaping it with the rigour of a researcher rather than the voice of a victim. He asks: Why do city dwellers look down on rural people? Is it a clash of temperaments or of interests? And does the city see the countryside as merely lagging behind in development, or as fundamentally backward?

The author writes from a position in ‘the middle’: a city-born man raised among rural folk, their schoolmate, comrade-in-arms and neighbour. He never saw in them the caricatures painted by urban conversation. He sees the difference as cultural, not moral, rooted in environment, not in superiority. The rural person is not guilty for failing to master the city’s language, and the city is not innocent for ‘welcoming’ those who do not resemble it. The conflict, as revealed in the book, is not about individual behaviour. It is the result of long-standing policies—land and power imbalances—and flawed cultural representation.

The birth of Nasiriyah was never simply about constructing a city. It was about constructing a multi-layered project of dominance, in which geography became a tool for controlling the tribe. It transformed the authority of the sheikhs into that of administrative agents under the watch of the Sublime Porte, and later the British Crown.

Everything began with a decision to grant tribal sheikhs ownership of the land, a bureaucratic act that altered the fate of the countryside. The sheikh became a tax collector, and the peasant, became a labourer on ancestral land. And so, the migration began. The tax-evading peasant knocked on the city’s door seeking a chance at life.

City is no paradise

But the city is no paradise. Its gates are well guarded. The rural newcomer, even if expelled from his own land, is treated as a stranger. At best, he is given a reed hut on the outskirts. Hence the symbolic title of the book. The Reed Hut is a nod to the Sumerian civilisation, which recorded humanity’s first cries on the tablets of Gilgamesh: “O reed hut! O wall!” As if humankind, from the dawn of history, has been screaming from the margins.

Among those who helped the author gather testimonies of forgotten lives were individuals from both town and country, from orchards and old quarters alike. They spoke of long-standing injustice, of stories that hovered between fear and concealment, of a memory too timid to say its own name. Most refused to give their full identities. Fear, of the tribe, of authority, of ‘shame,’ still lingers, as though history has yet to be rewritten.

But the book is more than a lament. It is an interpretive and analytical inquiry into the structure of the city—into its genesis—and how Nasiriyah evolved from tribal commons into urban bureaucracy. In Abdul Sattar’s view, the city is not merely an architectural entity but a “theatre of power,” a stage born in the wake of global political shifts, following the opening of the Suez Canal and Iraq’s emergence as a strategic corridor for great powers. The city came into being as part of a reformist agenda under Midhat Pasha. But it was not built on a void. It rose upon the corpse of a collapsing tribal system, seeking to redraw geography with a ruler’s hand.

Prone to flooding

The land selected for building Nasiriyah was chosen with care. In a cruel twist of fate, it was a site prone to flooding, as if the authorities wished to remind its inhabitants daily that land, like power, is never fixed. Under the supervision of a Belgian engineer, the city was laid out as a modern rectangle, with seven wide streets, a wall with four gates, gardens, institutions, a market, telegraph services, a government complex and a fully symbolic infrastructure suggesting the birth of a new order.

But change did not unfold horizontally. With the founding of Nasiriyah, class divisions manifested starkly in the city’s physical layout. Between the districts of Saray and Sayf and those of the reed huts, between those granted free homes and those who built their shelters from straw and palm fronds, the contrast was architectural but reflected the structure of power. Land that had once been held in common became state property, only to pass into the hands of the sheikhs. In this transition, the peasant moved from belonging to dependency.

In his research, Abdul Sattar traces how Al-Muntafiq—once a tribal entity—was transformed into a political unit. He examines the origin and evolution of its name, analysing how internal rivalries among the Saadun families and the purchase of official posts with gold turned leadership into a game of power rather than a traditional entitlement. Even the symbolic trappings of leadership were not fixed, but a matter of bidding wars between Istanbul and the tribal elders, between wealth and allegiance.