Since the dawn of humanity, the arts have been inseparably woven into the fabric of human existence. In literature, specific genres have been associated with specific environments. The nomadic life of the desert, for example, has long been linked with the rhythm of poetry, while the metropolis—a far more recent construct—has been linked with the novel, such that the Hungarian critic György Lukács once declared: “The novel is the daughter of the city.”

Of course, the novel transcends such spatial boundaries, venturing into deserts and remote regions to convey the full range of human experience across diverse landscapes. Interestingly, over the past year, a wave of Saudi novels has embraced this expansive narrative approach, choosing to revisit the historical narrative of the Arabian Peninsula, exploring its historical layers, and chronicling its pivotal early transformations and moments of enlightenment as it moved toward urbanisation. These works, detailed here, delve into the tensions between the Bedouin world—steeped in custom, tradition, and challenge—and the urban realm, with its comforts, stability, and modernity.

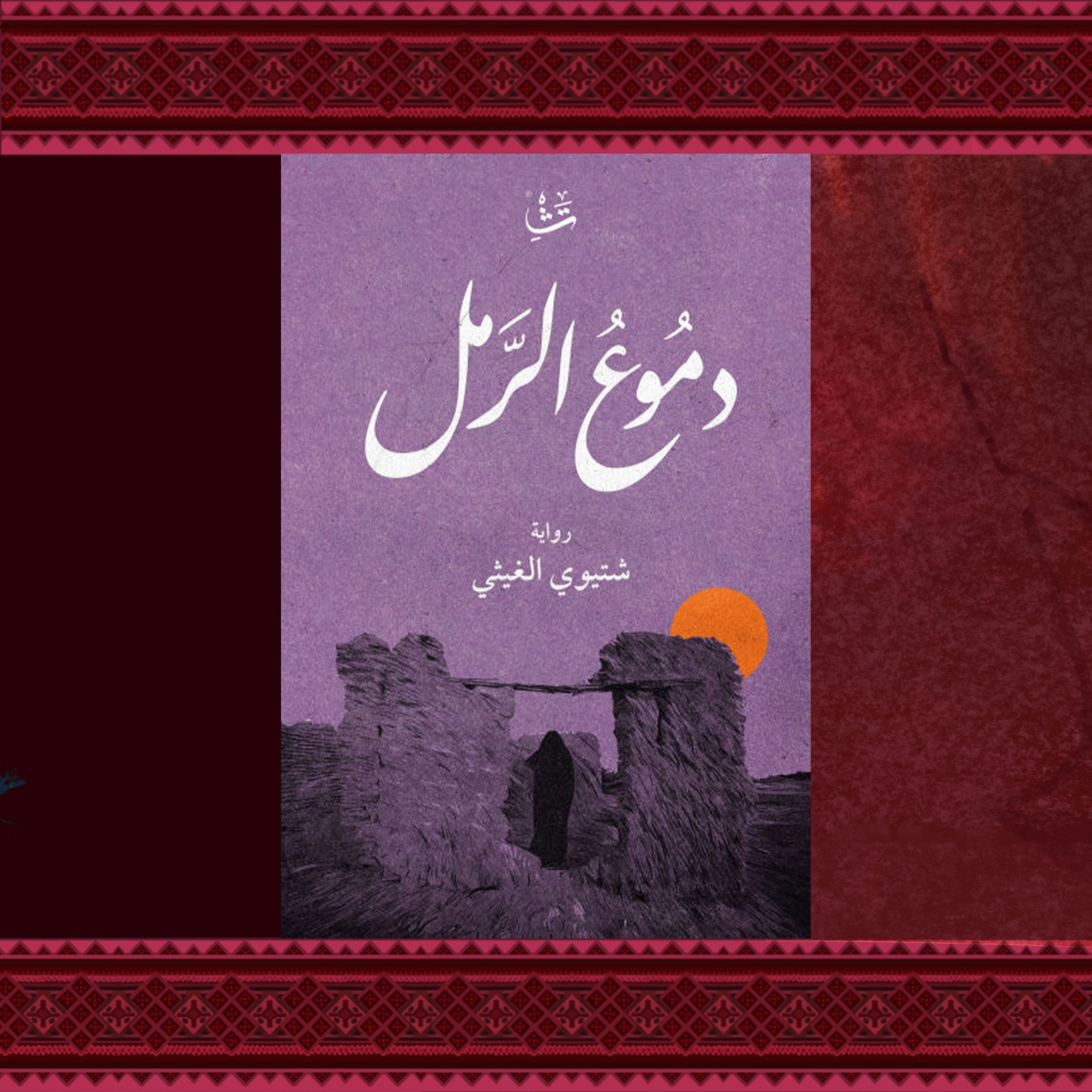

Tears of Sand

By: Shtaywi Al-Ghaithi

Published by: Tashkeel House

Winner of the 2024 Golden Pen Award for Most Influential Novel, Tears of Sand is a return to history from its opening lines. The narrator resolves to chronicle the life of his grandmother, Noweira, believing her story is worthy of preservation, for “life is memory”. Though 40 years have passed since her death, her story remains vivid in his mind. As the narrative unfolds, her personal journey expands to encompass the broader tale of her father and tribe, locked in a continuous struggle for survival.

As the narrative shifts to Noweira’s perspective, the desert appears in its stark austerity: tents woven from goat hair, meagre supplies, and a tribal society governed by strict customs and expectations. For a woman alone, survival is fraught; she must seek protection under a man’s care—even if, like Noweira, she possesses a resolute spirit, rebuffs suitors, and carves out a space for herself within her world. When her father leaves for war, she is eventually compelled to marry Abu Salem, the man she fiercely rejected. He marries her solely to father a son, then divorces her. Yet fate draws her back to him.

The narrative moves seamlessly between Noweira’s harsh desert life and the wartime backdrop against which the novel unfolds. The storyteller is deeply committed to documenting a pivotal chapter in Saudi history, focusing on King Abdulaziz Al Saud’s campaigns to unify the northern regions of Najd—especially Ha’il and its environs—despite limited resources. In stark contrast, Ibn Rashid wielded formidable strength, supported by state-of-the-art Ottoman military equipment and logistical backing.