Upon entering Damascus following its liberation from Ottoman rule in 1918, Emir Faisal Ibn al-Hussein announced that appointments to government positions would now be based on merit, rather than familial, tribal, political, or sectarian affiliations.

He appointed two prominent Christians (Fares al-Khoury and Yusuf al-Hakim) as ministers of finance and public works, respectively, named a Shiite from Baalbek (Rustum Haidara) as his advisor, and gave a member of the Druze community (Rashid Tali’a) the Interior Ministry. Faisal also appointed another Druze (Emir Adel Arslan) as Deputy Military Governor.

Ever since, Druze figures have appeared on Syria’s political stage. Some, like Sultan Pasha al-Atrash, led the national struggle against colonial rule. Others took part in military coups. Fadlallah Abu Mansour and Amin Abu Assaf executed President Husni al-Za’im in 1949, and Salim Hatoum arrested President Amin al-Hafiz in 1955.

The first Druze minister in Syria was Abdel Ghafar Pasha al-Atrash, appointed Minister of Defence in 1941. Later, Shawkat Shuqayr became Chief of Staff in the 1950s, while Abdel Karim Zahreddine became Army Commander in the early 1960s. Here, Al Majalla offers a short synopsis of the main Druze figures whose names have become so closely linked to the modern history of Syria.

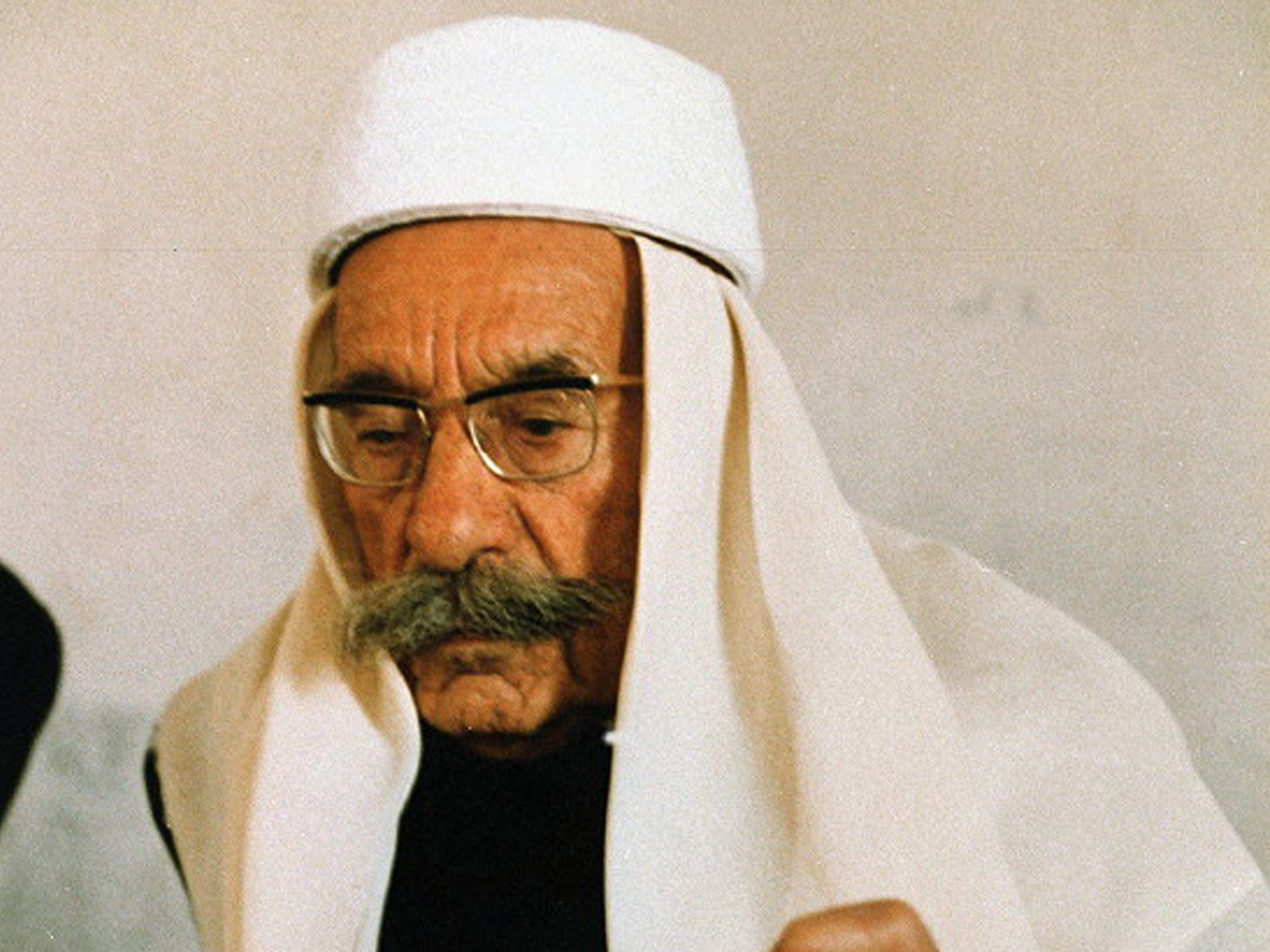

Sultan Pasha al-Atrash (1891–1982)

Commander-in-Chief of the Great Syrian Revolt, Atrash is the most prominent and revered Druze figure in modern Syrian history. He served in the Ottoman army, then joined the Great Arab Revolt led by Sharif Hussein against the Ottomans in 1916 and entered Damascus with Prince Faisal in 1918. When France divided Syria into mini-states at the start of the mandate period, Atrash was offered the governorship of the Druze Mountain.

He refused, insisting on nothing short of complete unity of Syrian lands, and in August 1922, the rebel Adham Khanjar sought refuge there after a failed attempt to assassinate French High Commissioner Henri Gouraud. France responded by ordering Khanjar’s arrest and execution, destroying Atrash’s home, where Khanjar had sought shelter.

In the summer of 1925, Atrash launched the Great Syrian Revolt against the French, which lasted until 1927. He rallied prominent nationalists like Abdul Rahman al-Shahbandar, Nasib al-Bakri, Shukri al-Quwatli, and others. France retaliated by repeatedly bombing and torching Druze Mountain. It also shelled Damascus on 18 October 1925, sentencing Atrash to death.

He fled to the Azraq region in Transjordan, then to Qaryat al-Milh in Saudi Arabia, only returning to Syria after a general amnesty was issued in 1937, shortly after the election of Hashem al-Atasi as president. Atrash came close to launching a second revolt when the French bombed Damascus again on 29 May 1945, but it was called off after a British-brokered ceasefire was announced on 1 June.