The job of national security adviser is a presidential creation, neither established in legislation nor requiring Senate confirmation. Ideally, the adviser connects the president to other senior officials, assures that he hears all relevant viewpoints, and sees that his policy decisions are translated into action. In practice, the ability of advisers to function effectively depends less on the process they establish than on the proclivities and preferences of the president they serve.

Few presidents had thought less about the management of national security policy the day they entered the White House than Donald J. Trump. He had run for president without really expecting to win and focused little on the details of governing even after he did. In the White House, Trump has eschewed formal process and expertise and instead relied on his often changing impulses.

Each of Trump’s three national security advisers has tried, with mixed success, to tailor to the president’s instincts a process that brings government expertise to bear on decision-making. Bolton was perhaps substantively and temperamentally the most suited to help Trump pursue his “America first” foreign policy. But even he found himself on the outs with this decidedly mercurial president. And Bolton’s core style—rushing to decisions, excluding advisers with dissenting views—may have brought short-run results, but over time it was a recipe for policy disaster.

A TEXTBOOK PROCESS REBUFFED

Trump’s original choice for national security adviser, retired Lieutenant General Michael Flynn, had been his campaign’s most senior adviser on national security policy. Flynn was an odd choice. He had extreme views on the threat of Islamic terrorism, questionable relationships with foreign entities and governments, and a rosy view of Russia. He had also been fired from his last government job for managerial incompetence. But Trump valued loyalty, and he ignored the entreaties of both President Barack Obama and Chris Christie, the original chair of his transition team, who warned the incoming president against appointing Flynn.

Flynn was in over his head from the outset. He was supposed to establish himself as the single center of power on national security affairs in the White House. But instead he competed for access, attention, and control with figures such as Steve Bannon, the president’s chief strategist, who secured a seat on the main Principals Committee of the National Security Council (NSC), and Jared Kushner, the president’s son-in-law, who served as the main conduit between Trump and certain foreign governments. Before Flynn could do much more than hire a few people who shared his dark view of the world, he was embroiled in controversy centering on his contacts with the Russian ambassador after the election. Ousted just 24 days into the job, Flynn set a record for the shortest tenure of anyone serving in the position.

Flynn was one of few national security figures Trump knew personally, and when it came time to replace him, Trump had to improvise. For other such appointments, he had opted for people who looked the part—either strong generals such as James Mattis and John Kelly, whom he appointed as secretaries of the Departments of Defense and Homeland Security, or successful corporate executives such as Rex Tillerson, the ExxonMobil CEO who became Trump’s first secretary of state.

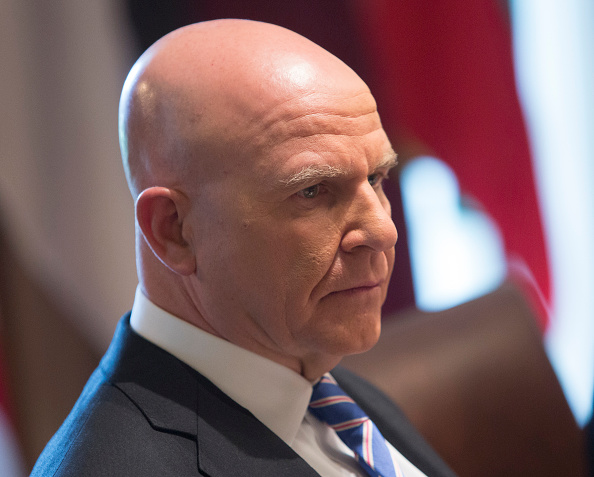

Now Trump found another broad-shouldered army officer, Lieutenant General H. R. McMaster, to take the national security adviser job. McMaster had a storied career as a combat veteran in Iraq and Afghanistan. He was also a well-respected defense intellectual, having helped draft the army’s counterinsurgency strategy in Iraq and written a stinging critique of military leadership during the Vietnam War. McMaster’s appointment was widely welcomed in Washington’s corridors of power. Arizona Senator John McCain, long a leading Trump critic, noted approvingly that he “could not imagine a better, more capable national security team than the one we have right now.”

Though he had never before served in Washington, McMaster approached the job with textbook precision. He met with all of his living predecessors and asked for their advice. He weeded out some of the more ideological staffers Flynn had brought in and reassured the many diplomatic, military, and intelligence officials detailed from other agencies that he respected their service and work, even if they hadn’t been part of the Trump campaign. He reinstated the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the intelligence director to the NSC’s Principals Committee (Flynn had removed them) and brought homeland security back under the NSC’s auspices (Flynn had separated it). He moved Bannon off the NSC committee. And he established routine meetings at multiple levels for the purposes of both long-term planning and crisis response. McMaster’s was a textbook NSC process.

But Trump had no interest in detailed policy briefings or long meetings devoted to considering all available options. The president believed in his gut over advice and process: “My gut tells me more sometimes than anybody else’s brain can ever tell me,” Trump once declared.

McMaster never caught on. He would brief the president with formal, elaborate presentations. He called meetings to go over every detail of policy. But he never established the sort of close, informal relationship with the president that was essential for success. Other players soon understood that Trump was ignoring McMaster’s process—and so they began to ignore it as well. Mattis and Tillerson met frequently to decide what to do, leaving McMaster out of their deliberations. And they would often ignore his directives or send lower-level people to the meetings he called. McMaster soldiered on. But in the end, he was no doubt relieved when Trump told him in March 2018 that it was time for him to go.

A BRASH ADVISER ON A LEASH

Enter John R. Bolton, a national security player with long experience and strong views, many of which were more aligned with Trump’s “America first” perspective than McMaster’s had been. Bolton understood that Trump didn’t want structured meetings and detailed briefings. He set out to streamline the NSC staff by eliminating positions dealing with such issues as cybersecurity and global pandemics. He reduced the frequency of interagency meetings. And he focused on supporting the president by giving him his best advice.

Like the president, Bolton preferred to work alone, behind closed doors, and he communicated with staff mainly by e-mail rather than face-to-face. He favored one-on-one meetings with other principals over the larger advisory meetings that characterized the NSC in previous administrations. The new tone was set within weeks of his coming to the White House, when Bolton decided not to convene a single meeting of the NSC principals prior to Trump’s historic Singapore Summit meeting with North Korean leader Kim Jong Un in June 2018 or before the president met with Russian President Vladimir Putin in Helsinki the next month.

By acting outside of formal processes, Bolton, who was 70 years old, could seize what was probably his last opportunity to change policy to his liking. He had long seen arms control, international agreements, the United Nations, and other multilateral institutions as unacceptable constraints on U.S. power and sovereignty. Now he moved quickly to withdraw the United States from the Iran nuclear deal and the Reagan-era treaty eliminating intermediate-range nuclear forces. He was the force behind Trump’s speech to the UN General Assembly last fall, which was a broad indictment of multilateralism and defense of sovereignty. He put his stamp on hard-line policies with respect to Iran, North Korea, and Venezuela.

As long as he was pushing in a direction that Trump supported, or for policies that didn’t engage him, Bolton enjoyed a lot of leeway to get things done. But sometimes his views ran afoul of Trump’s instincts—notably, the president’s conviction that he could negotiate great deals with everyone and his fear of getting dragged into a new war.

Trump made clear, for example, that he disagreed with Bolton’s uncompromising line on North Korea—so much so that he left Bolton out of the last-minute meeting with Kim Jong Un at the demilitarized zone earlier this year and openly contradicted his assessment of the North’s missile threat. Bolton was also initially left off the invitation list for a meeting with Trump and his top advisers on Afghanistan, in that case because he opposed withdrawing U.S. forces from the country. Trump likewise reversed Bolton’s push (supported by many other top advisers) to retaliate when Iran downed a U.S. drone. “He wants to start 3 wars a day,” Trump once complained of Bolton, “but I have him on a leash.”

To those concerned about Bolton’s inclinations, such restraint was reassuring—to a degree. “I am the national security adviser,” Bolton has admitted. “I am not the national decision-maker.” But there was only so much comfort to be found in a willful president constraining a willful national security adviser. For Bolton was the polar opposite of the model for the job established by Brent Scowcroft, national security adviser to President George H. W. Bush, and followed in the main by Scowcroft’s successors. Bolton was an ideologue who thought he knew the answers, excluded those who disagreed, and destroyed relationships and institutions that took his predecessors decades to build. To the extent his tenure served the president, it came at great cost to the nation.

Sooner or later, most presidents settle on a national security adviser who meets their personal and operational needs. Sometimes that choice is good for the republic, sometimes not. For the office is a two-edged sword. In a harmonious administration, the occupant both serves the president and runs a policy process that engages senior officials and prepares issues for presidential decision. But in a fractious administration, the adviser can use that closeness to the president to drive rash actions that reflect the idiosyncratic predilections of the adviser, the president, or both.

“Presidents get the national security process they deserve,” Stephen Hadley, President George W. Bush’s national security adviser, once rightly observed. But the nation deserves better.

This article was originally published on ForeignAffairs.com.