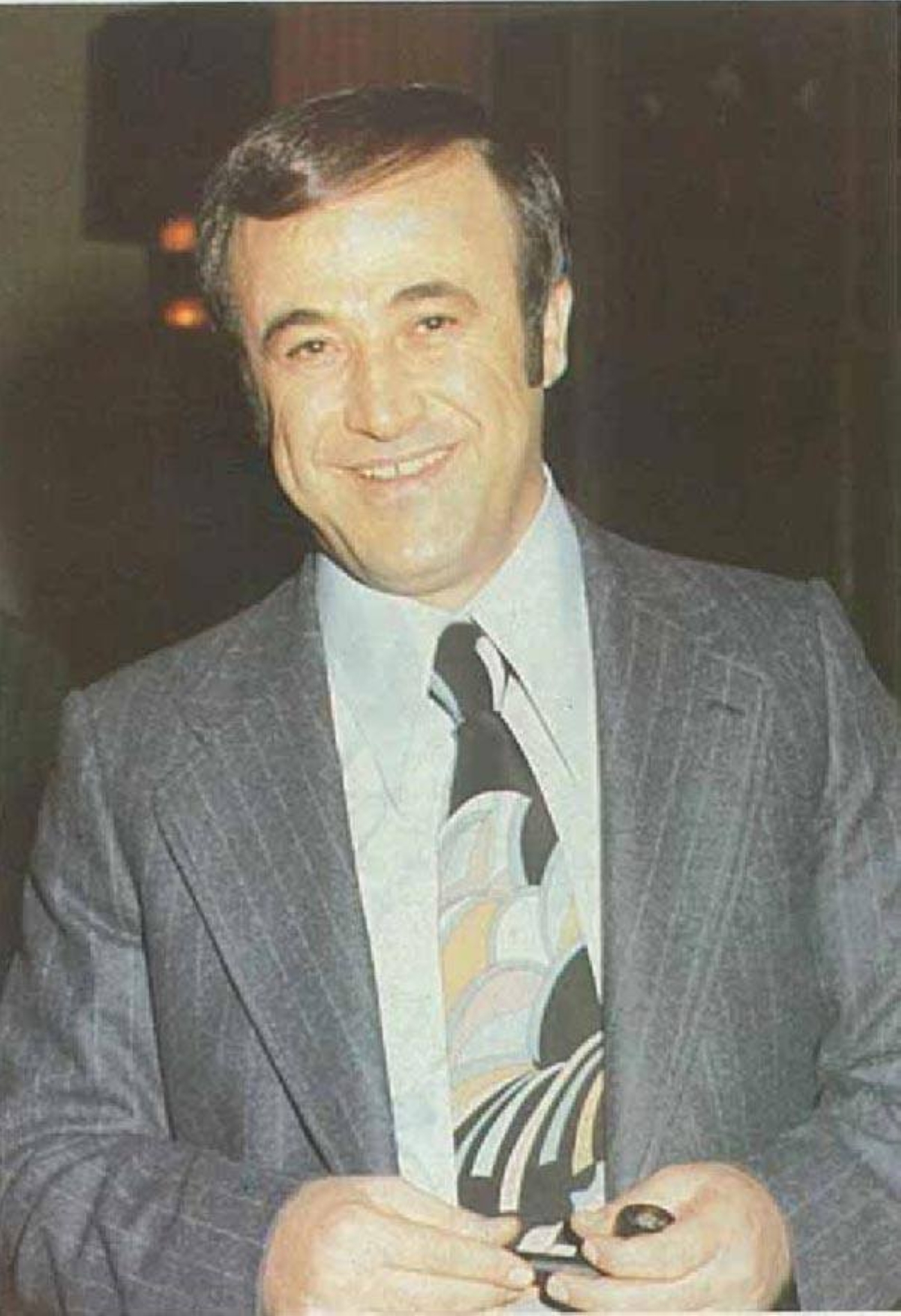

One of the last big things Rifaat al-Assad ever did was flee Syria, having lived long enough to see his family’s half-century of rule come crashing down, the armed forces he once led dissolving after a lightning two-week offensive from rebels based in Idlib.

A military officer and former Vice President of Syria, Rifaat was the uncle of the recently deposed president, Bashar al-Assad, and brother of Bashar’s predecessor and father, Hafez al-Assad.

Rifaat fled to Lebanon, then to the United Arab Emirates, where he died not in a palace, a command centre, his hometown, or even in the prison many felt he belonged, but in exile. He had fled Syria before, escaping the wrath of his elder brother (Hafez) in 1984, banished to Europe for more than three decades for trying to seize power.

A rare witness to the regime built and hardened by Hafez through force, Rifaat had long dreamed of succeeding his brother—a dream he pursued through rivers of blood, including most notably the 1982 massacre in Hama, when forces under his command killed 10,000 Syrians in less than a month. It remains the single deadliest act of violence perpetrated by an Arab state against its own people in the history of the Middle East.

A centre of gravity

Few figures in the history of authoritarian regimes live as long as Rifaat, so few expected him to see what he once sought to inherit unravel before his eyes. That he had to stand powerless on the sidelines, unable to shape the course of events, is more than a passing irony; it is a political paradox, heavy with meaning.

Rifaat al-Assad was never merely the president’s brother. He embodied one of the regime’s most entrenched pillars: a security apparatus that grew into a power centre and, for a time, a rival. Hungry for power, Rifaat challenged Hafez in 1984 and lost. He later became a liability. When the regime finally fell, he was neither a participant nor an insider, but still on the margins, where he had stood for four decades.

Initially, he was more than just a peripheral figure orbiting Hafez. Over time, he became a centre of gravity within the system itself, with networks spanning the realms of security, military, and party. Known for his fiery temperament, he wielded what amounted to an “elder brother’s sword” over the heads of would-be rivals.

A pivotal moment came in 1983, when Hafez’s illness opened a path that Rifaat began to read as succession. Two sons of a large coastal family shaped by rural poverty, the brothers began as partners. Hafez set the course, and Rifaat followed, echoing his major choices, and occasionally testing the limits. Over the years, they gradually grew into rivals, which ultimately led to a rupture that could not be repaired.

Rising up the ranks

Rifaat joined the Baath Party in 1952, then entered the army in the early 1960s, retracing Hafez’s route into the upper ranks of the military and the party. Seven years older, Hafez had become Minister of Defence by 1966. In adulthood, as in childhood, Rifaat lived in the shadow of his older brother.

He moved through compulsory service and entered the Ministry of Interior after Syria’s secession from the union with Egypt in 1961. When the Baathist Military Committee seized power in March 1963, with Hafez among its members, Rifaat enrolled at the Military Academy in Homs. After graduating, he served alongside Hafez, who by then commanded the Air Force.

Rifaat’s first notable military episode came alongside Salim Hatum, a senior Druze military officer and early Baathist, in the storming of President Amin al-Hafiz’s headquarters in February 1966, an operation led by military officer and far-left Baathist leader Salah Jadid. Although Nureddin al-Atasi was secretary-general of the party from 1966-90, it was Jadid who wielded the power.

During that time, the Assad axis began to crystallise in opposition to Jadid, the architect of the 1966 intra-party coup. Not yet a senior commander, Rifaat’s alignment with this faction laid the groundwork for a partnership that would later become decisive. In February 1969, the Assad brothers used the military in Damascus to target several of Jadid’s centres of power.

Right-hand man

It was a ‘soft coup’ but prepared the ground for the moment on 16 November 1970 when Hafez seized power, removing both Atasi and Jadid. Rifaat was tasked with securing Damascus. Hafez took his place in the Republican Palace, while Rifaat was on the streets, commanding the force that would protect it. Rifaat became head of the Defence Companies, an elite formation that functioned as a quasi-independent army.

His influence expanded through the party and into universities, youth and women’s organisations, and the media. He also established the Higher Association of Graduates, a parallel student arm that consolidated his reach among the university-educated. Over time, his power only grew. He became a key point of contact for international companies seeking entry into Syria, adding economic influence to his military standing.

In 1976, the long-running confrontation between the regime and the Muslim Brotherhood flared again, reviving a conflict that had first erupted in 1964 and would later intensify sharply in December 1979. At a Baath Party conference, Rifaat argued that the time had come to “respond with force”.

He said that “ten million lives were sacrificed to preserve the Bolshevik Revolution” and that Syria must also be prepared for a comparable toll “to preserve the revolution”. He then pushed his rhetoric further, vowing to “fight a hundred wars, level a million fortresses, and offer a million dead” in defence of the regime. Rivers of blood followed.

The Muslim Brotherhood uprising between 1979-82 was brutally crushed, reaching its dreadful peak in the bombardment of Hama in February 1982. From that moment on, Rifaat became known as “the Butcher of Hama”. In 1983, he dispatched paratroopers to Damascus with orders to forcibly remove veils from women in the streets. This triggered public outrage. Hafez had to apologise and publicly denounce his brother’s actions.

Ascent blocked

When Hafez fell ill in November 1983, Rifaat sensed an opportunity. He began behaving as the designated successor, mobilising support among the generals. Some began shifting allegiances. Others in the regime moved to block his ascent. Defence Minister Mustafa Tlass, Foreign Minister Abdul Halim Khaddam, Chief-of-Staff Hikmat al-Shihabi, and Military Intelligence Director Ali Duba aligned themselves with Hafez.

Secretly, they were preparing for clashes. Anti-armour weapons were handed to the Republican Guard and Military Intelligence. Army and air force units were placed on high alert, anticipating a confrontation with Rifaat’s forces, which then encircled Damascus and controlled its main entrances. As Hafez recovered, he created a committee to manage state affairs.