Writers born in Egypt between the 1930s and the 1950s typically shared an experience of exile that shaped their works. Amidst the era’s political storms, authors such as Andrée Chedid and Robert Solé had to leave their homeland, their suitcases an outward sign of their forced departure, their notebooks a symbol of their imagined return.

Some did return to the Egypt of their childhood, but found that its demographics and social features had changed beyond recognition. Only broken memories remained, which they tried to repair with words from pens matured in exile. What they produced was a kind of literature of longing.

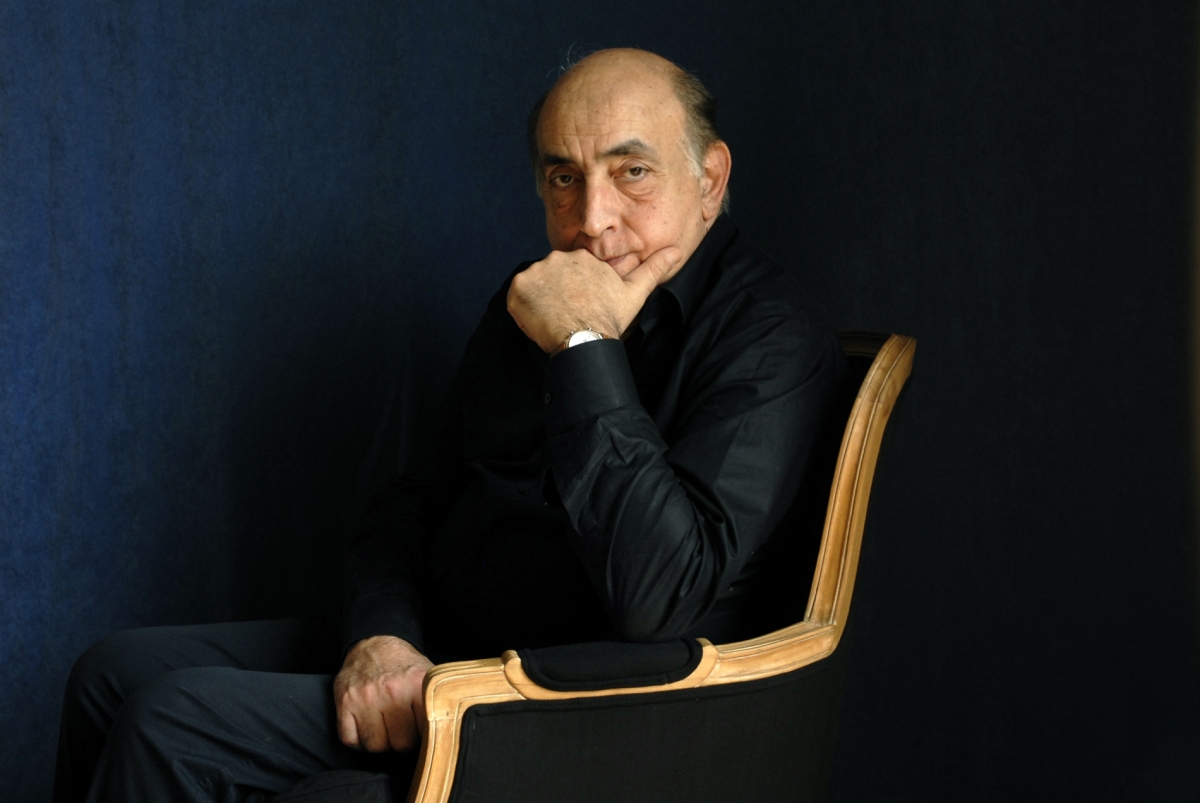

Gilbert Sinoué, born in Cairo in 1947, is one of the voices to have embodied the notion of a ‘cultural bridge’ in contemporary French literature. He has blended the precision of the historian with the passion of the novelist, reshaping Eastern memory through a Western tongue. For Sinoué, writing is not the mere narration of events; it is an inquiry into the spirit of the East.

In his major epic Avicenna or The Journey to Isfahan, he did not simply present a biography of the Sheikh al-Rais (meaning Chief or Leader of the Wise, a term used to describe the Persian polymath Ibn Sina, also known as Avicenna). Instead, he celebrated the brilliance of the Eastern intellect and its radiance, turning what appeared to be arid history into a human journey alive with knowledge and emotion.

Reaching for a homeland

Despite the breadth of his Eastern horizon, Sinoué’s relationship with Egypt remains exceptional. He does not write about Egypt as a tourist or a detached observer, but as a son searching for a lost homeland between the lines on the page. This impulse is especially evident in his novels that chronicle cosmopolitan Egypt—that magical crucible where cultures, languages, and religions once fused in rare harmony. Sinoué seeks to restore the features of ‘Royal Cairo’ and Egyptian cities that once pulsed with life and diversity, portraying them as a lost paradise to be rebuilt through words.

Behind the literary name ‘Gilbert Sinoué’ lies the story of a Cairene child named Samir Kassab, born on 18 February 1947 to a father from the Greek Catholic (Melkite) community and a mother from the Sephardic Jewish community. Samir was educated at the prestigious Holy Family School (Jesuit) in Cairo, where both his language and emotional sensibility took shape, until he earned his baccalaureate.

The contours of his personality were not formed solely in classrooms but in the vibrant aristocratic milieu in which his father, Maurice Kassab, was a central figure and familiar name within the Greek Catholic community, whose experience managing entertainment ventures made him one of King Farouk’s close associates. Given the king’s fondness for nightlife, he entrusted his friend Maurice with a special mission: to establish and run a casino modelled on exclusive French clubs.

Thus, by royal decree, the Scarabe Casino was born in 1948, becoming the only private gambling club in the Middle East at the time. The dominance of Scarabe did not last long, however. It fell victim to the Cairo Fire of January 1952, and the final curtain was drawn with the July Revolution that same year, when Kassab’s father was placed under house arrest for a year because of his close ties to the royal regime.

Maurice Kassab’s spirit of adventure remained unbroken. Years later, he leased a neglected government yacht that had once belonged to the late king but had been left abandoned on the banks of the Nile. Named Qassed Khair, Maurica transformed the yacht into a floating restaurant that would later become one of the most elegant and celebrated aristocratic destinations of the era.

A place of enchantment and beauty, it drew major international stars. Charles Aznavour and Dalida performed on its decks, while the young Samir accompanied his father at work, breathing in the scent of stardom and the passion for French culture that filled the air—scenes and nostalgia that later resurfaced in his novels.

From Camus to Cairo

The striking paradox in the journey of Gilbert Sinoué (Kassab), an only child, is that his family had no connection to literature. Books were largely absent from a household dominated by commerce and the management of high-end restaurants. Amid his parents’ constant preoccupations, the boy found himself hemmed in by solitude within the walls of his Cairene home. He escaped the “tedium of loneliness” by reading.

“My journey naturally began with the worlds of Alexandre Dumas and Jules Verne, before moving on to Chateaubriand, Camus, Sartre and Céline. This was followed by my immersion in the great classics of the novel and then modern literature. I devoured two or three novels a week. Albert Camus undoubtedly left an indelible mark on me and remains, for me, a master thinker. The Plague is one of the greatest achievements of the 20th century; it is rare to encounter a singular intellectual who is also a brilliant novelist,” Sinoué said.

In that household, language was a living blend of Arabic and French. His mother, like most members of her social class in Egypt at the time, was resolutely Francophone (English was not heard). That linguistic and emotional mix, coupled with a solitude punctuated by French philosophers and novelists, produced what would distinguish Sinoué’s work: a confident French, animated by the instinct of an Eastern hakawati (traditional Arab storyteller).

At 18, Samir Kassab made a decision that altered the course of his professional and existential life: he chose to leave his old name behind and assume a new identity drawn from Egyptian history. It stemmed from his encounter with The Egyptian by the Finnish novelist Mika Waltari. The novel traces the life of a Pharaonic physician and close confidant of Akhenaten, a pharaoh who temporarily moved ancient Egypt from polytheism to monotheism, and who was ultimately exiled.

Samir’s admiration for the character was not fleeting; it reached what he later described as “complete identification”. As he would later say: “I identified completely with that Egyptian physician; I felt as though I were his living embodiment.” In an artistic impulse, he changed his name to Sinoué and left for Paris at 18 to study the guitar at the École Normale de Musique, later teaching music for several years.

From lyrics to novels

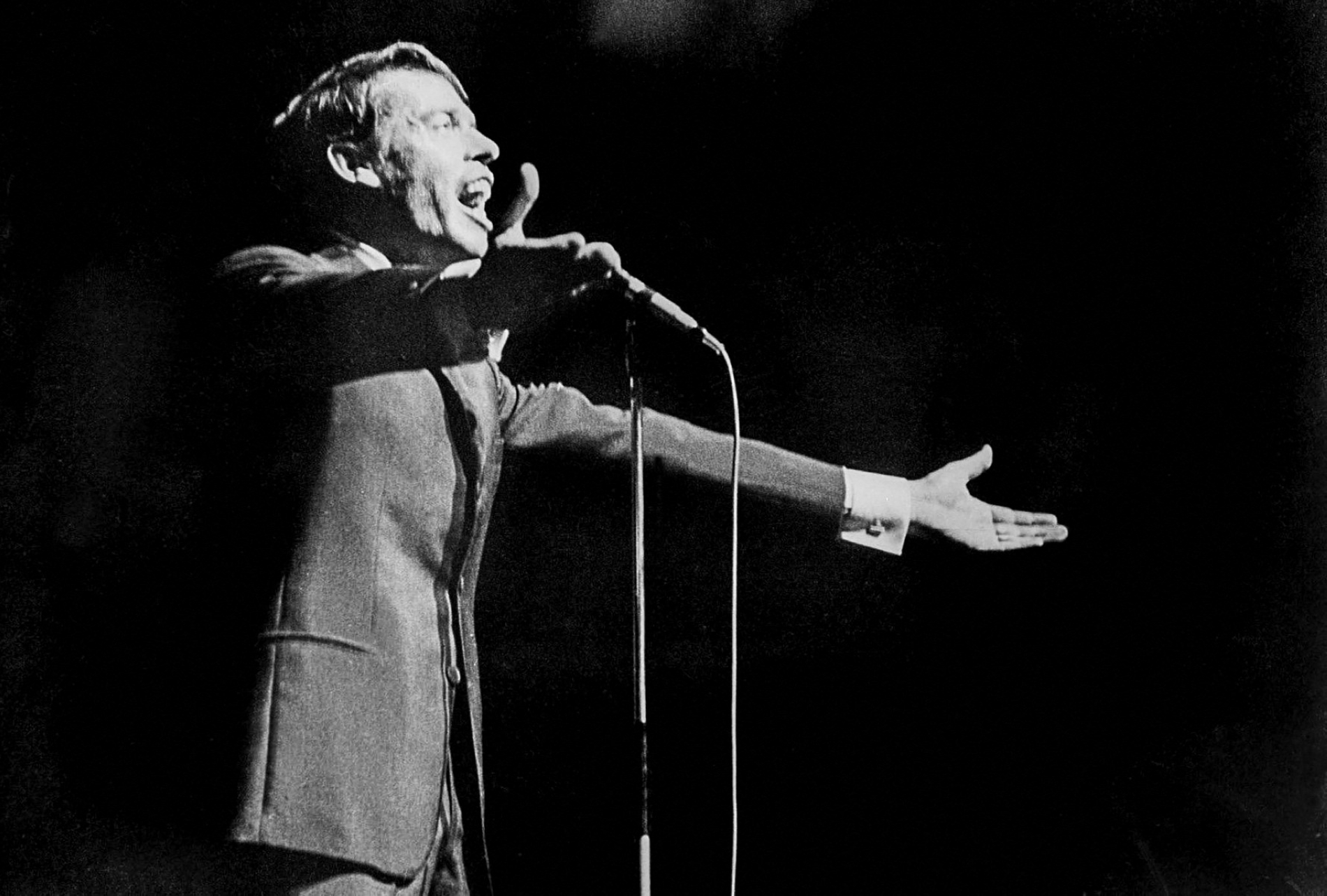

He immersed himself in melodies but never truly put down the pen, writing poems and short texts in secret. One day, his composer friend Jeff Barnel noticed a set of lyrics on his desk, then set them to music for the singer Isabelle Aubret to perform in a song that sparked a prolific artistic career. Sinoué’s success as a lyricist led him to collaborate with giants of French music, including Dalida, Claude François, and Jacques Brel.

For Sinoué, a song is a “miniature novel”, where events and dialogue are compressed into a matter of minutes. He believes this formed a kind of musical apprenticeship that later honed his craft as a novelist, teaching him to write with focus and economy, avoiding unnecessary digressions and excessive description.

Only at the age of 38 did Sinoué start writing novels, delayed by what he called a “fear of comparison”. For him, the likes of Camus were gods, inhabiting a different world. “It was impossible for me to believe that I might one day belong to the (same) planet as Camus,” he later said. Approaching 40, however, he felt that time was slipping away, what he called the “edge of the slope”. He did not want to die without having fulfilled his childhood dream. This “phobia of endings” was a driving force.

“Reading quite simply led me to writing,” he said. “Surprisingly, my discovery of Jacques Brel’s song lyrics had a profound impact on me. In my view, he was not merely a singer but a singular writer who deeply inspired me. One cannot devote one’s life to a profession without an inner calling, especially in art... Yes, writing was my inner calling; I have always been possessed by the magic of words.”

Plunging into novels

In 1987, Sinoué published his first novel, The Purple and the Olive Trees, in which he revisited the life of Callistus I, the bishop of Rome and an early Pope who was killed for being Christian and is now venerated as a saint by the Catholic Church. It met with a modest reception but was enough to draw attention to his talent for shaping historical imagination with knowledge and depth.

In 1989, he published his second novel, Avicenna, or The Journey to Isfahan. This was his big breakthrough. He chose a complex historical figure from the 11th century, shifting from early Christian history to the heart of Islamic civilisation. In his book, Sinoué does not treat history as a sequence of static events but as a human epic that can transcend religions and cultures. It firmly established him within the contemporary Francophone literary landscape.