Artificial intelligence made huge strides in 2025. The technology moved from technical noise and experimental language models to a hard economic and geopolitical engine, reshaping international alliances alongside the evolution of major corporate structures.

For the Arab world, and particularly the nations of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), this was not simply a year of adopting new tools—it was the year in which economic diversification took clearer shape as a strategy linking artificial intelligence and energy.

That shift was driven by major developments that began with US President Donald Trump’s trip to Saudi Arabia in May, followed by Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman's visit to Washington in November.

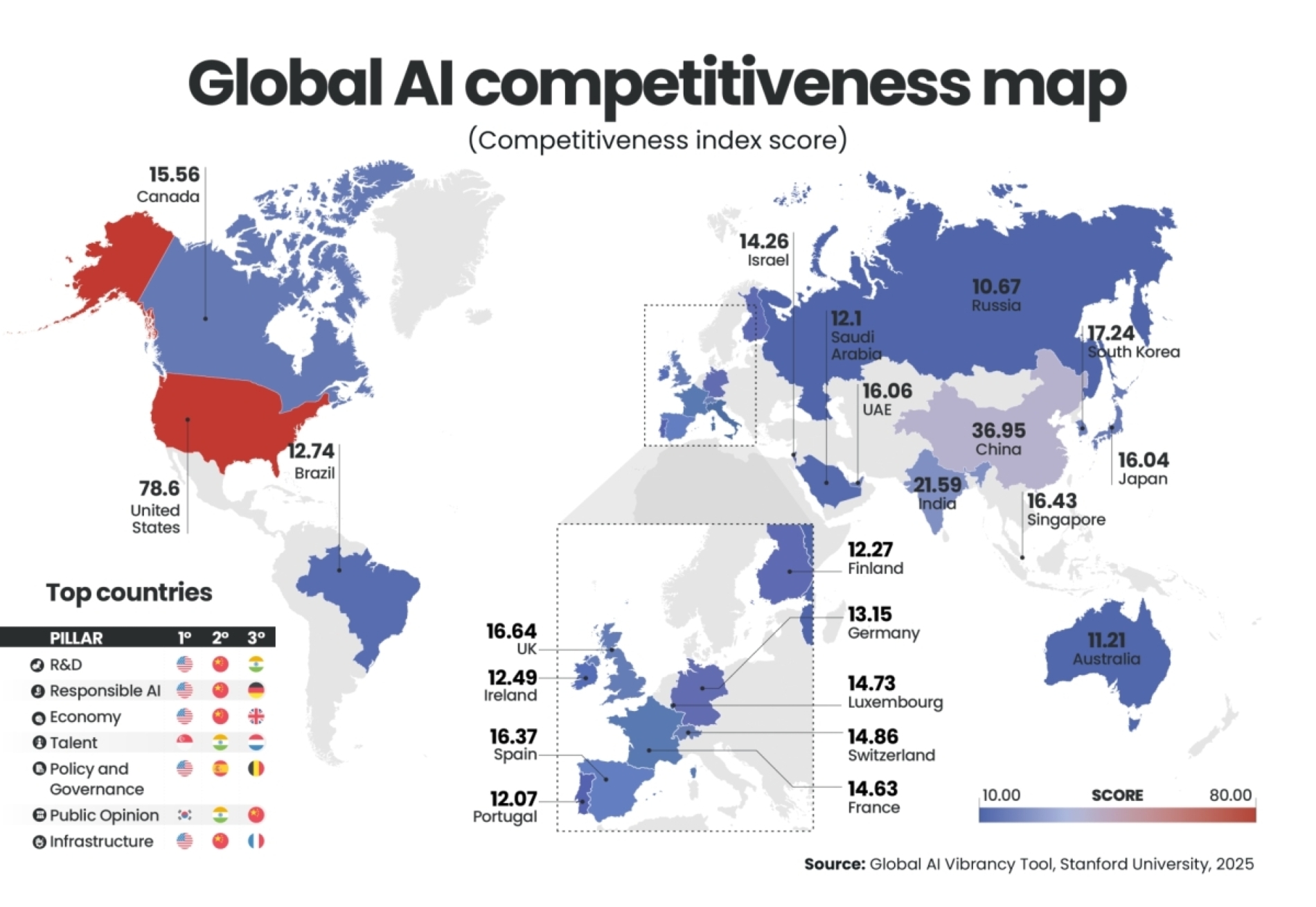

As the cyber cold war between the US and China intensified, 2025 was shaped by three core economic dynamics. The first was the replacement of the traditional oil-for-security equation with a new formula: chips and infrastructure in exchange for capital and influence, or petrodollars for technodollars (technology-backed capital). This was reflected in the lifting of restrictions on the export of Nvidia chips to Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

At the same time, major companies began decoupling revenue growth from headcount growth by deploying intelligent agents, triggering qualitative and quantitative waves of redundancy. Meanwhile, electronic chips evolved into strategic goods, subject to unprecedented sovereign-style taxes and trade restrictions, as seen in Trump’s conditional offer to China and Beijing’s rejection of it.

The ‘Gulf-Nvidia axis’

The year brought a profound restructuring of US-Gulf relations, no longer driven primarily by oil exports, but by Washington’s need for economically anchored alliances capable of mobilising capital for re-industrialisation, matched by the Gulf’s need for advanced computing power to secure its economic future.

Trump’s Gulf tour differed from previous diplomatic visits that focused on counter-terrorism or stabilising oil prices. This time, the agenda was dominated by the economics of artificial intelligence and sovereign capability, culminating in a fundamental shift in export policy. The Trump administration prioritised direct economic gains and strategic alignment over the more cautious restrictions of its predecessor, approving the export of advanced Nvidia chips to Gulf entities.

Read more: US, Saudi Arabia enter 'golden era' in defence, AI partnership

In Saudi Arabia, memoranda of understanding focused on the critical minerals required for artificial intelligence hardware. In the UAE, President Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed announced a $1.4tn investment in the US over the next decade, spanning technology, artificial intelligence, and energy. In Qatar, major investments in US technology sectors were unveiled, reinforcing Doha’s role as a financial hub for the emerging digital economy.

The November visit of Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince to Washington gave these arrangements an institutional, political, and economic character. Supply chain resilience and regional instability formed the overarching themes.

The summit between Trump and the Crown Prince went beyond protocol to deliver concrete economic frameworks. It opened with a nuclear technology agreement, as negotiations achieved a breakthrough towards a civil nuclear cooperation deal, a step of major importance for powering energy-intensive data centres. It also included a partnership aimed at securing supply chains for uranium and rare earth elements, both critical to the semiconductor industry, with the stated goal of reducing reliance on Chinese processing.

The talks also finalised agreements that allow Saudi entities, including HUMAIN, to acquire up to 35,000 Nvidia Blackwell chips, enabling the country to develop sovereign large language models. These agreements triggered a wave of purchases and positioned Humain among the leading global compute operators, supporting Vision 2030’s digital transformation ambitions.

The UAE, as a strategic partner of Microsoft, secured licences enabling G42 to import large quantities of Nvidia chips. The deal required G42 to remove Chinese equipment from its infrastructure, a concession it was prepared to make in order to strengthen its position as a global node for artificial intelligence.

The silicon war

As US-Gulf relations warmed strategically, the technology cold war between Washington and Beijing entered a new, more volatile phase in late 2025, shaped by unconventional American trade policies and Chinese defensive manoeuvres.

In December, Trump announced a policy shift regarding semiconductor exports to China, reversing the previous blanket ban on advanced chips. The administration proposed allowing Nvidia to sell its H200 chips to accredited customers in China. The H200 is powerful, but one generation behind the latest Blackwell line. The US condition was unprecedented. It required the payment of a 25% levy, or a share of revenues, to be transferred directly to the US government.

The administration argued that the blanket ban was harming American companies, including Nvidia, AMD, and Intel, by depriving them of revenue from the world’s largest semiconductor market. Those lost revenues, it said, also indirectly supported Chinese domestic innovation, including Huawei. The 25% levy was presented as a mechanism to protect national security, create American jobs, and preserve US leadership in artificial intelligence.

Beijing’s response was swift, but conducted in the style of a quiet war. While China’s foreign ministry publicly stated that cooperation would benefit both sides, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology and Chinese regulators moved to block acceptance of the offer in practice through non-tariff barriers. A new procurement rule required local companies to justify why Chinese chips could not meet their needs before they could place orders for American hardware. In effect, that bureaucratic requirement nullified the US proposal.

Read more: AI and the future of jobs

The rise of agentic AI

The most unsettling corporate development of 2025 was the transition from generative artificial intelligence, which creates content, to agentic artificial intelligence, which carries out actions. The shift has profound implications for organisational structure, profitability, and the labour market.

In 2024, companies used artificial intelligence to draft emails, write work-related notes, and support demanding tasks. In 2025, agentic systems, commonly described as agents, were increasingly used to manage entire workflows. Agents gained the ability to reason, plan, and execute multi-step tasks independently, such as handling a customer service claim end-to-end and issuing a refund without human involvement. By mid-year, 62% of organisations surveyed by McKinsey were experimenting with agents.

This economic harvest came with a clear and unsettling human cost. The narrative that artificial intelligence will not replace you, but someone using artificial intelligence will, began to fade as agentic systems demonstrated the ability to replace the person entirely in specific roles.

The technology and services sectors saw layoffs explicitly attributed to efficiency gains from artificial intelligence. Employees were leaving not because markets were shrinking, but because the nature of work was changing.