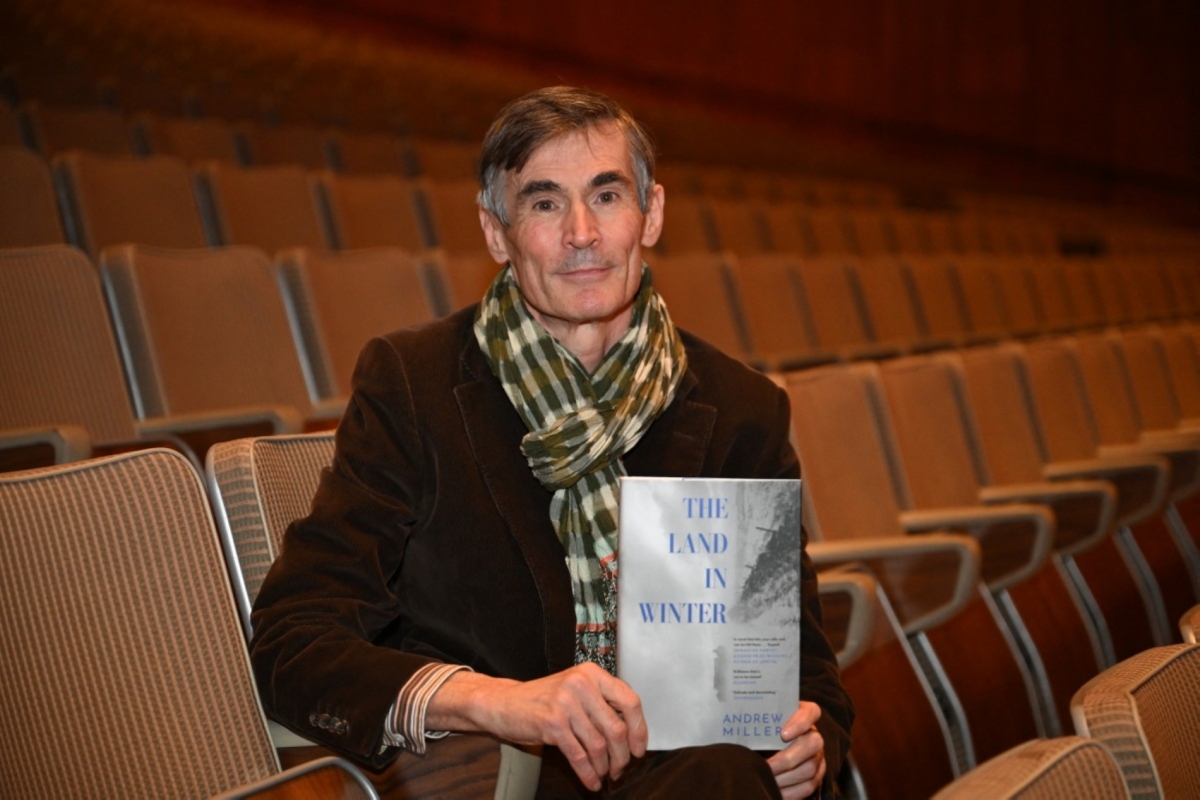

The award-winning British writer Andrew Millar is known for capturing nuance and using deftly drawn characters to explore the forces that shape lives and experience. In an interview with Al Majalla, he says writing can be seen as more of a fibre optic camera than a mirror, and why he tries to say as little as possible.

This is the conversation.

The Land in Winter is set during Britain’s coldest winter in 1962. What drew you to this particular moment in history, and how did it shape the emotional landscape of the story?

I was born in 1960. I think I was reaching back into my early childhood, and perhaps, more particularly, into the young married lives of my parents. Once I began researching the period, I became increasingly excited about it. It’s the egg from which the modern world, or the bit of it I know, is hatched.

The characters in the novel seem haunted by their pasts and constrained by their present. How do you approach writing such emotionally layered individuals?

I’m a non-essentialist. I don’t believe in a core self. This leaves me free to come at the character from a variety of angles. When characters behave in a contradictory fashion, when they are marked by paradox, that's when I start seeing them clearly.

Literature has always been a mirror, but also a provocation. Do you see your fiction as primarily reflecting the world, or as challenging and reshaping it?

A mirror suggests a passivity that does not align with the experience of writing. A provocation suggests something too much like a mission statement, some intention extraneous to the work itself.

How about a mirror that moves like a fibre optic camera threaded into a vein and gently shoved towards the heart? I could go with something like that.

You won the Costa Book of the Year award and have been shortlisted for major prizes. Do awards change the way you see your own work, or are they just background noise?

Definitely the latter, but it’s a noise you need to hear once in a while.

Some writers say prizes bring recognition but also pressure. Have you ever felt they affected your freedom to write?

In some ways, winning a prize takes the pressure off. When I won the Costa prize for Pure, I felt that afterwards I could write more or less anything and it would, at the very least, be accepted. If you have written a book that is critically and commercially considered a failure, then a second failure might be fatal, or at least mean that publishers shrug and give up on you. That's pressure!