We meet him at last in Damascus, clutching the notebook that never leaves his side, a companion for recording impressions from his travels across the globe.

"I cannot believe I am in Damascus," he says. "It is not only the faces that have changed, but the language itself. Language is not one-dimensional; it contains joints, tributaries, emotions and displacements. All I can do is expose what I see and speak of it as a human catastrophe.

"Damascus today is a skeletal husk, stripped of spirit by tyranny that has dragged it a century backwards. I roam its quarters like an ageing eagle, stunned beneath the tyranny of the sun, contemplating the void and silently asking: how did Damascus lose its ancient intimacy? Today, it stands as a symbol of erosion, the erosion of being and place in synchrony."

On rupture and the philosophy of flight

This anxious gaze upon place recalls his novel The Rupture and the question it poses: is rupture epistemological or geographical?

He replies: "I believe the fundamental rupture is with the self, first and foremost. It is also a physical and geographical necessity to confront the existential disarray I was experiencing at the time. In that novel, I stood in opposition to the world, declaring rupture under the banner: 'Flee, for you are free,' because remaining meant certain death.

"In truth, we do not recoil from places, but from the ideologies that govern them. We do not exchange one locale for another, but one mode of thought for another. In other words, rupture is not revelation. It springs from the daily life of the individual. What is essential in writing is to re-examine existence, not to indulge in verbal games or metaphors, nor to chase fame or acclaim.

"In my childhood, I wandered the deserts, and I was happy in those vast expanses saturated with light, vegetation and the myriad living beings that populated that space."

The lexicon of the desert

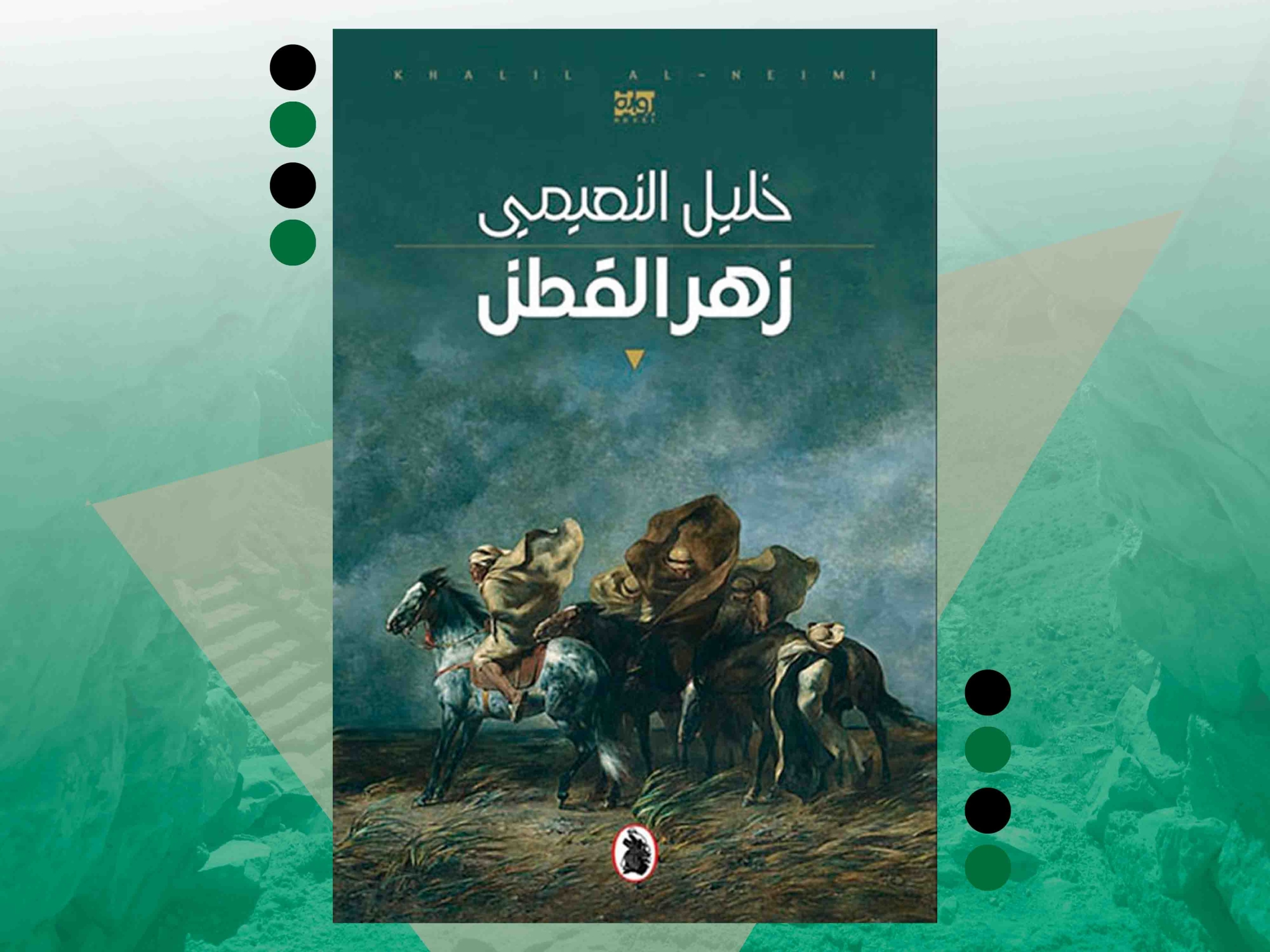

It is impossible to engage with al-Neimi's oeuvre without pausing at the desert—a locus that permeates his novels and imprints his prose like a talisman or protective amulet warding off oblivion.

This is not merely a fictional landscape but a deeply autobiographical one, drawn from the experience of a child cast into open vastness, who now, with matured awareness, probes both the harshness of survival and the translucence of souls. It is as though he never departed from the swirling tempests of the desert, where life, as the father tells his son in Cotton Blossom, "is measured by distance, not by hours."

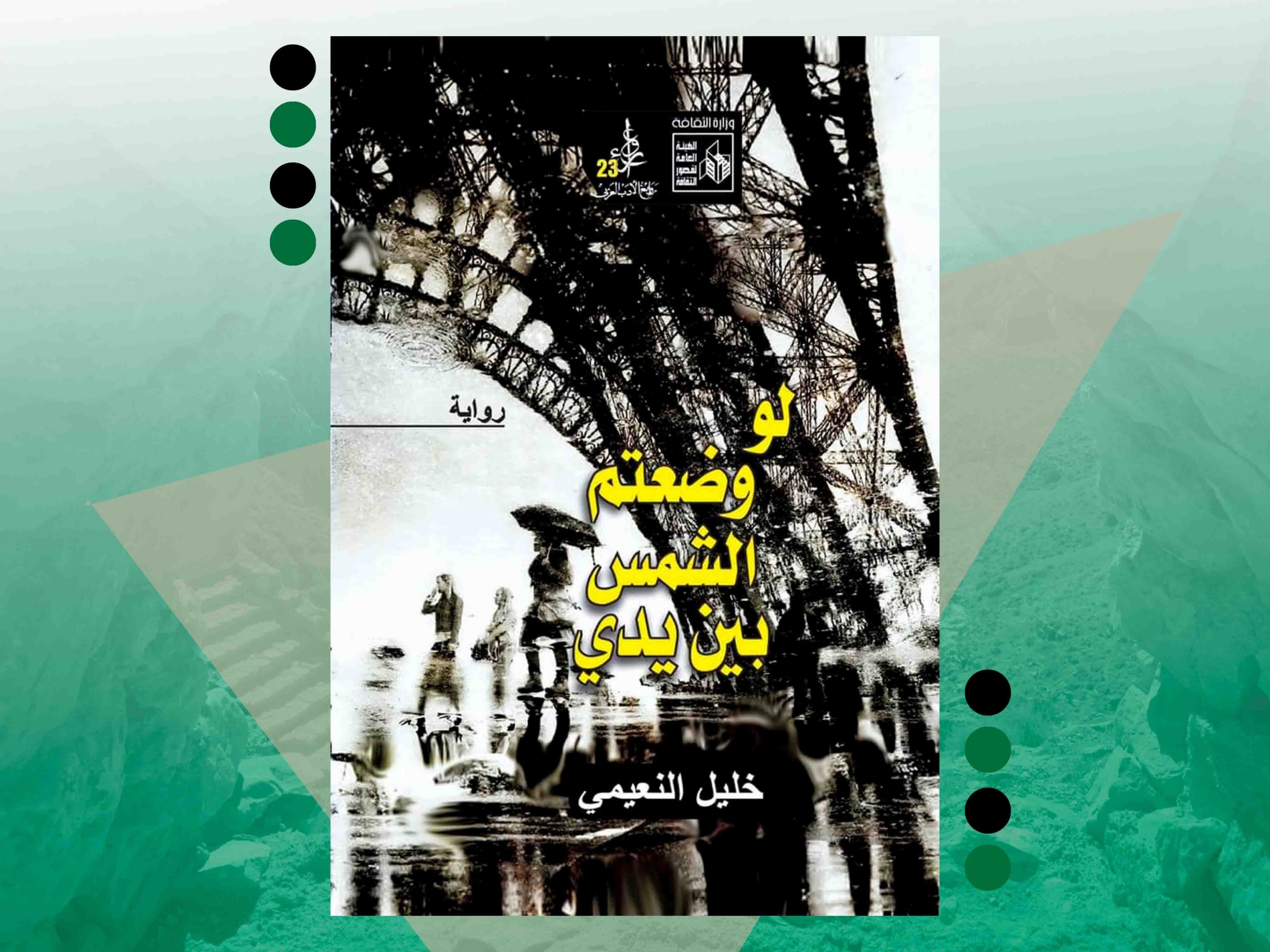

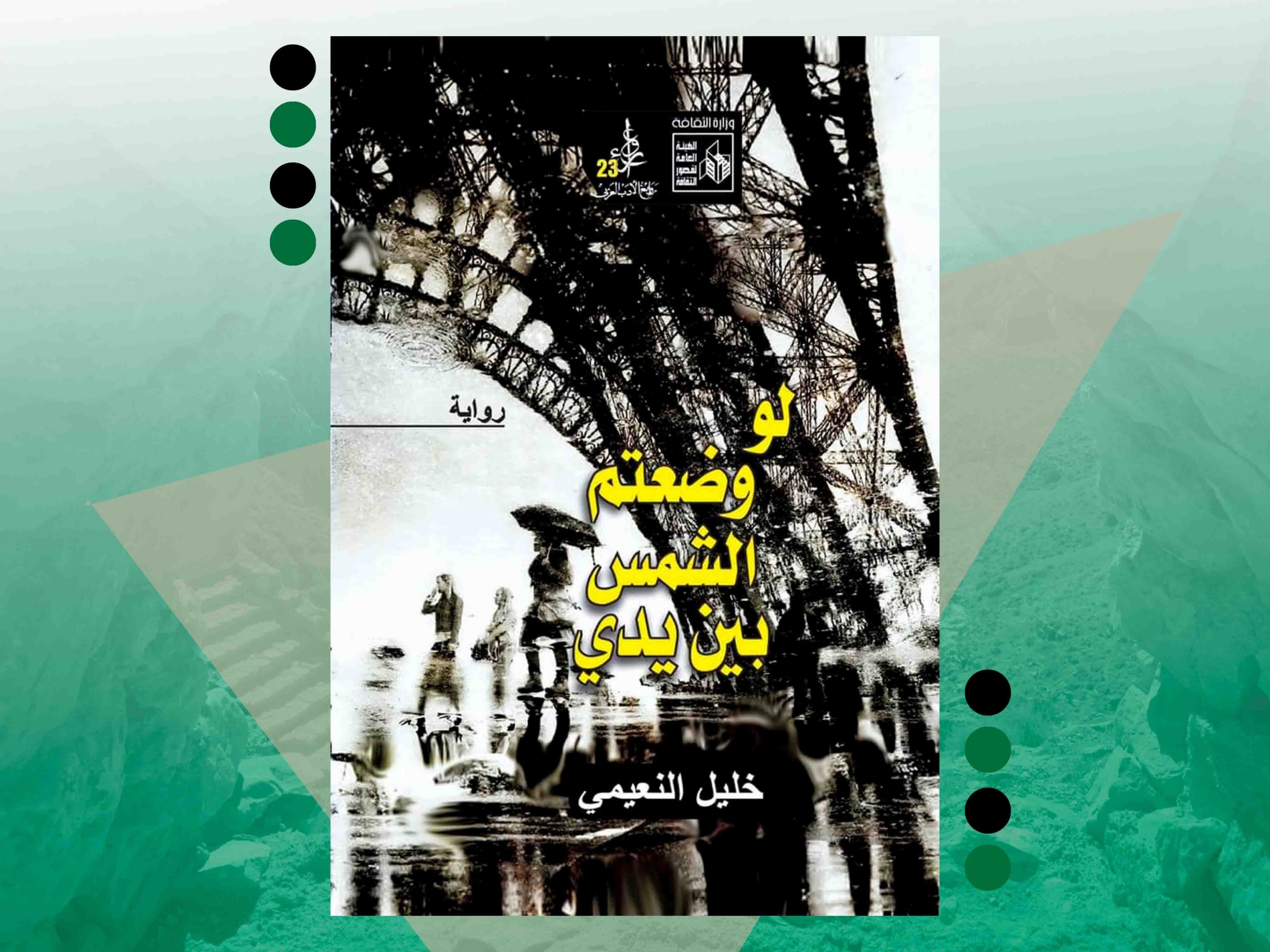

The author of If You Placed the Sun in My Hand momentarily drifts into reverie before confessing: "I lived my most beautiful days in the desert. What I wrote about it springs from a profound love for my birthplace, far removed from the orientalist gaze some seek to peddle in narrative form. I recall my aunt giving birth to a stillborn child during our travels. She buried him and continued on her way without once looking back. I cannot forget the joy that would seize me as I listened to thunderclaps, lightning, and the patter of rain in that exposed expanse, where no barrier stood between the muddy earth and the reckless clouds and wind."

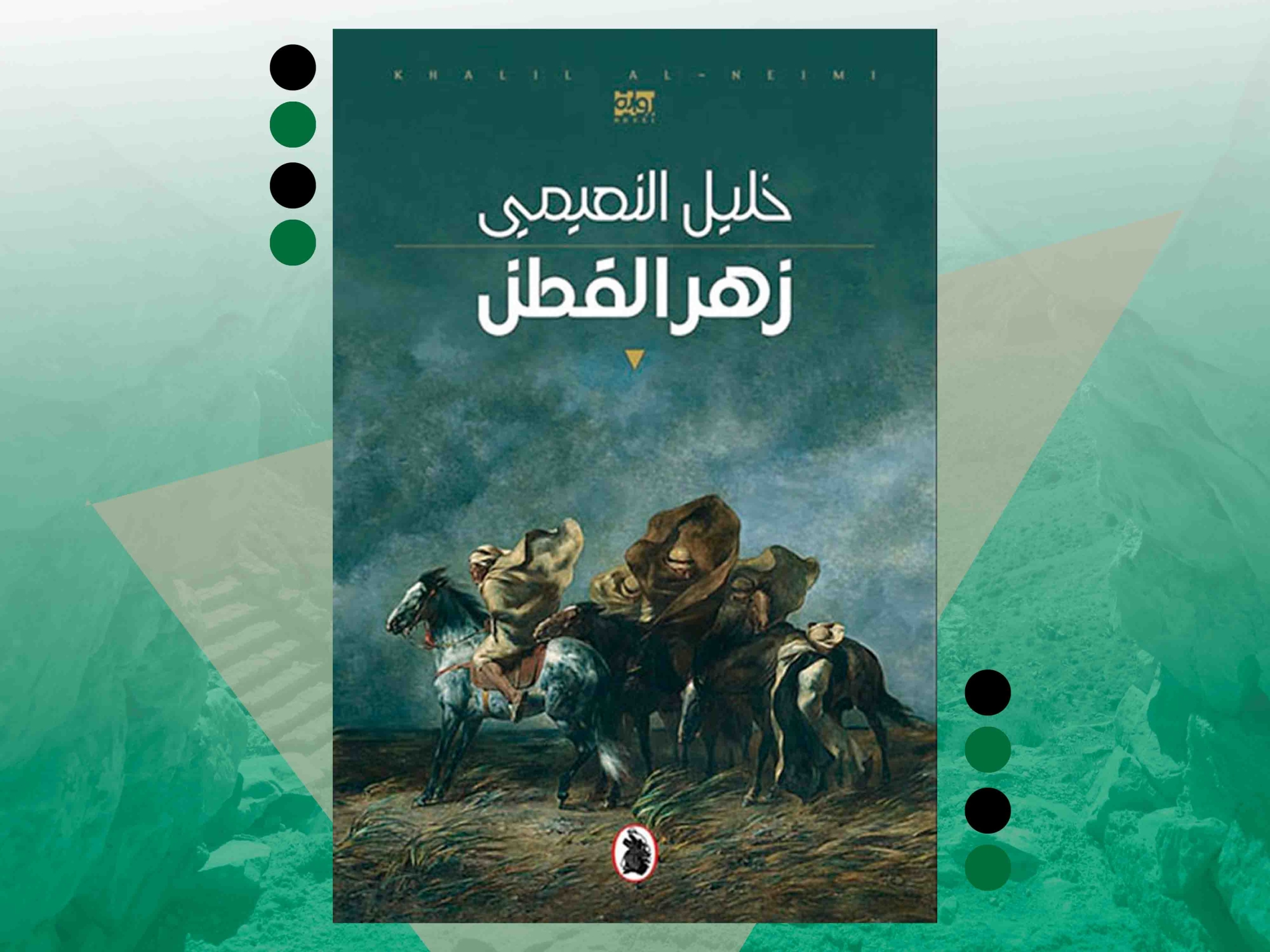

In his latest novel, Cotton Blossom, al-Neimi ventures into thorny narrative terrain, distilling it into a paternal aphorism: "Speech without substance becomes chaff, fit only to feed beasts."

A lexicon born of place

What distinguishes the author of The Tracker is his creation of a linguistic lexicon uniquely his own, an alchemy of Bedouin vernacular infused into the current of classical Arabic.

He refuses to falsify the spoken idiom of his characters. Instead, he sifts through the Bedouin dialect, threading it into the fabric of formal Arabic to forge a rhythm that grants each phrase its deepest resonance. Words like yadfir (to shove), yitamarrakh (to wallow), yaḥūṣ (to flail), and yatasalḥab (to slither) do not merely serve the logic of character; they clothe them in the feathers of place, its scent, and its shifting moods.

Al-Neimi elucidates the mysteries of his lexicon: "I discovered early on that Arabic is a single body, and that colloquial speech is part of the classical whole. Every environment possesses its own language for expressing the inner self.

"Some of the myths my father told me as a child I later found in Homer's Iliad and Odyssey. Linguistic expression, then, is never neutral. It may even be deceptive. That is why I will not abandon my narrative lexicon, for the imported language has corrupted Arabic literature. Language is not a metaphor, nor a ready-made recipe."

All we write is autobiography

Al-Neimi contends that all writing, in essence, is a form of autobiography. "No matter how we attempt to invent scenes, stories, or behaviours that diverge from our own," he reflects, "even when we play expressively with the truths we have lived, we are merely rewriting the same book in multiple forms."

Hence, he insists that form must be valued alongside the intellectual, linguistic and philosophical reservoir from which it springs.

Ultimately, everything a human being writes emanates from a single mind. Yet it is the genius of life, in its manifold dimensions, that allows us to imagine different shapes for our existence, whether they mirror our experience or depart from it. "There is, therefore, no fixed truth in reality or in fiction. What I perceive of myself," he adds, "is subject to the evolving tide of consciousness, in a process of perpetual transformation."

He holds a firm conviction: every autobiography is, in some sense, a falsification of personal history, and all other forms of creative expression are falsifications of that falsification. Creation is a dance of inscription and erasure, of construction and demolition. What matters is the text. And what matters most within the text is language.

The itinerant soul: a cartography of loss

On the other side of his literary persona, we encounter al-Neimi the traveller, restless in his pursuit of the Other, unravelling the riddles of place, people, and presence. A wanderer who has traced the planet's longitudes and latitudes, guided by a Bedouin nose attuned to the saffron scent of the earth.

From the Syrian steppe and cornmeal porridge, from the bewilderment of sand dunes to the Andes of Chile, from Konya and Istanbul to India and China, from Japan to Nouakchott and Samarkand, he follows in the footsteps of Ibn Battuta and the fantastical voyages of One Thousand and One Nights, inscribing a new chapter in the literature of travel.

"In my journeys," he says, "I was searching for the first place I was forced to leave. And I discovered that the central axis of travel is loss. I came to believe that place belongs to the one who creates it, not to the one who merely sleeps in it."