A century ago, on 2 October 1925, Scottish inventor John Logie Baird transmitted the first televised image using a mechanical prototype. It was of a mannequin in a London shop, but this was soon followed by a live transmission of his assistant’s face—the first practical demonstration of broadcasting moving images via radio waves. What Baird had done was transform light and sound into electronic signals, transmit those signals to a display device, then convert the signals back into recognisable pictures and sound. The television was born.

Baird’s experiments in 1926 would see him stage the first complete television demonstration before an audience. The invention would help transform the world. Over the next 100 years, television (or TV, as many came to call it) evolved from a rudimentary mechanical apparatus into a multifaceted digital platform, shaping people’s political, cultural, and public consciousness.

Its roots stretch back to the late 19th century, when scientists first sought to convert light into images that could be displayed on a screen. In the 1880s, German inventor Paul Nipkow designed a perforated rotating disc that transformed light into primitive images that could then be transmitted electrically. Years later, researchers developed the cathode ray tube, enabling clearer image rendering.

By 1928, just three years after Baird unveiled the first practical mechanical television, he achieved the remarkable feat of transmitting an experimental signal between London and New York. At the same time, young American inventor Philo Farnsworth introduced the first fully electronic television system, which was sharper, more reliable, and cheaper to produce. It quickly became the global standard for modern television.

Although the medium was still in its infancy, experiments in live broadcasting began in the late 1920s. In 1928, American inventor Charles Francis Jenkins established an experimental station in Maryland, known as W3X. It transmitted rudimentary black-and-white images that could be received by only a handful of devices, yet it laid the groundwork for what would follow.

Shaping memory

Over the coming decades, television expanded from a technological novelty into a central force in political communication, cultural expression, and shared human experience. From wartime propaganda to the moon landing, from political debates to big sporting events, television has shaped collective memory.

Today, at the age of 100, it faces the new challenge of navigating the digital revolution. Streaming platforms and social media have redefined the nature of media and entertainment, shifting viewing habits, including from the collective to the individual. Yet some events are still capable of uniting vast audiences in real time, such as major sporting tournaments, political debates, or global news events.

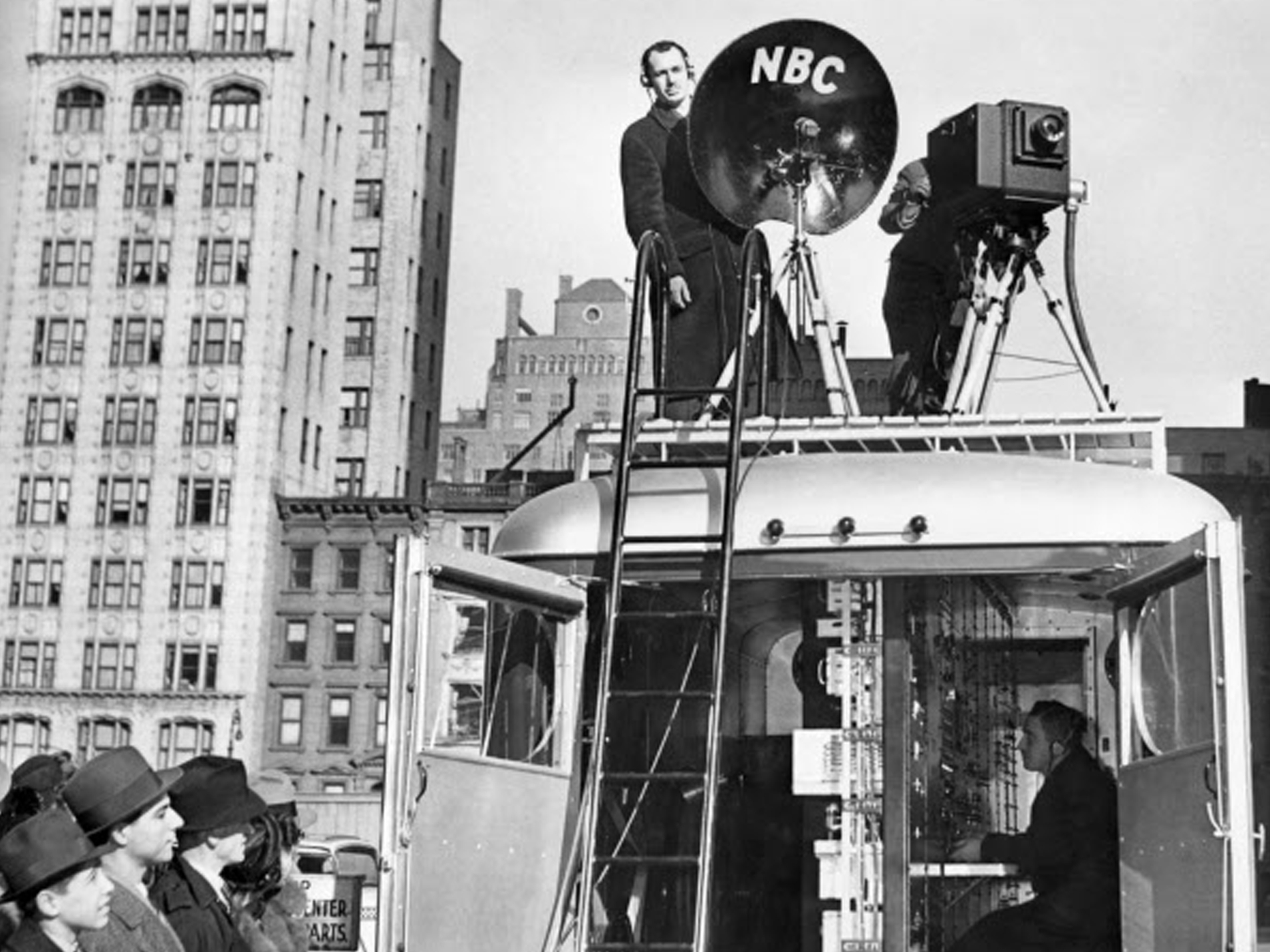

A decade after the first experimental broadcasts, the National Broadcasting Company (NBC) emerged in 1939 as the first major TV network in the United States, launching regular programming from New York. At the time, television sets were tiny—barely five inches across—and prohibitively expensive, yet they captivated the attention of elites and affluent households.

During the Second World War, military applications were prioritised over civilian applications. After the war, television began its mass expansion. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) standardised the analogue broadcasting system, allowing all televisions to receive the same channels with consistent quality. This analogue standard was only retired in 2009, after the transition to digital broadcasting.

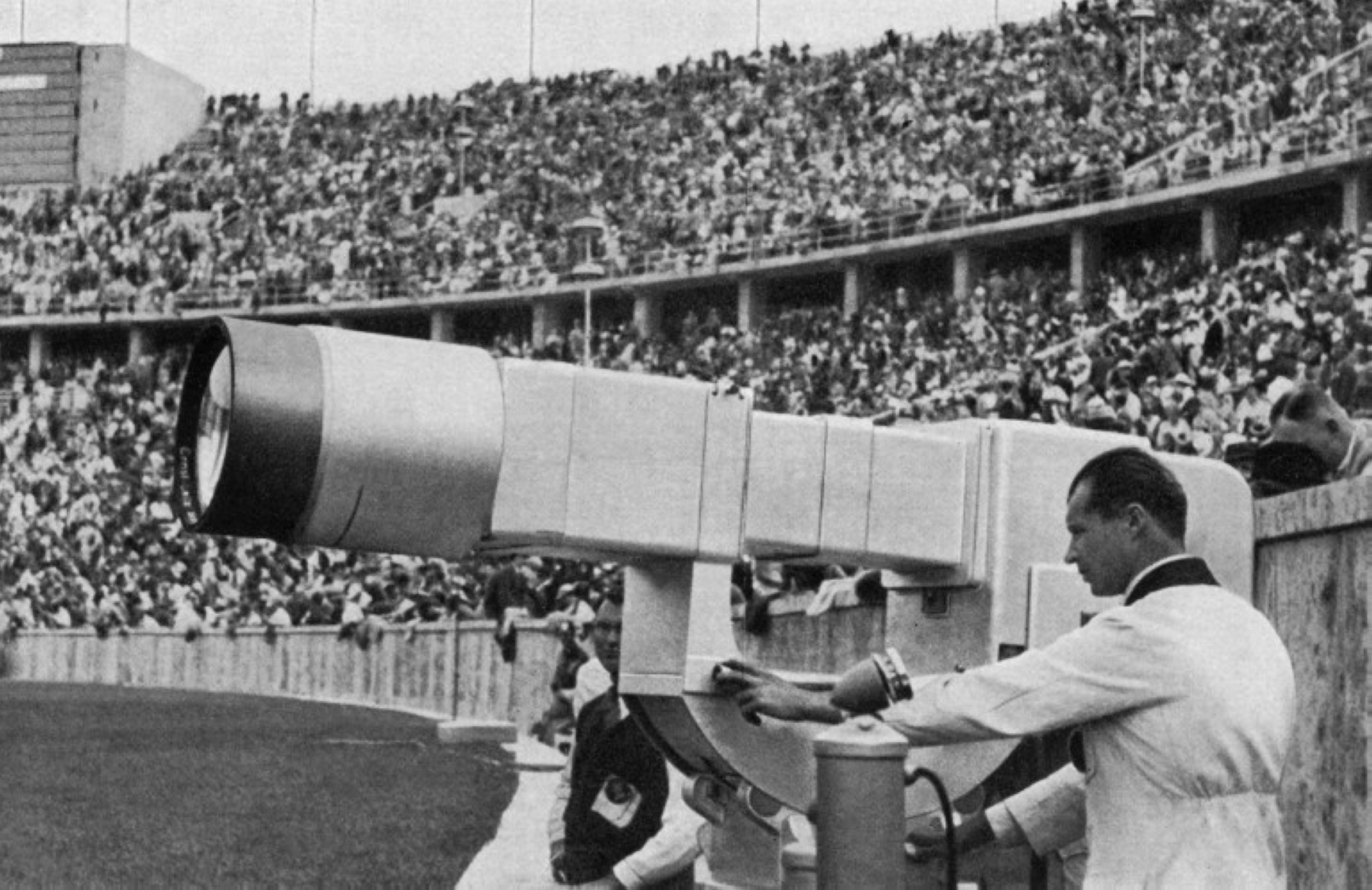

Nazi Germany once had ambitious plans for a “People’s Television” network—a cable-based system with screens installed in public spaces, broadcasting idealised portrayals of Aryan life and even the executions of Hitler’s enemies. It reflected how Germany’s Minister for Propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, understood the power of live imagery. Unlike reading or radio, TV visuals impose a curated reality directly onto the viewer. The Nazis had shown as much during the 1936 Berlin Olympics, also broadcasting speeches and events to reinforce Nazi messaging.