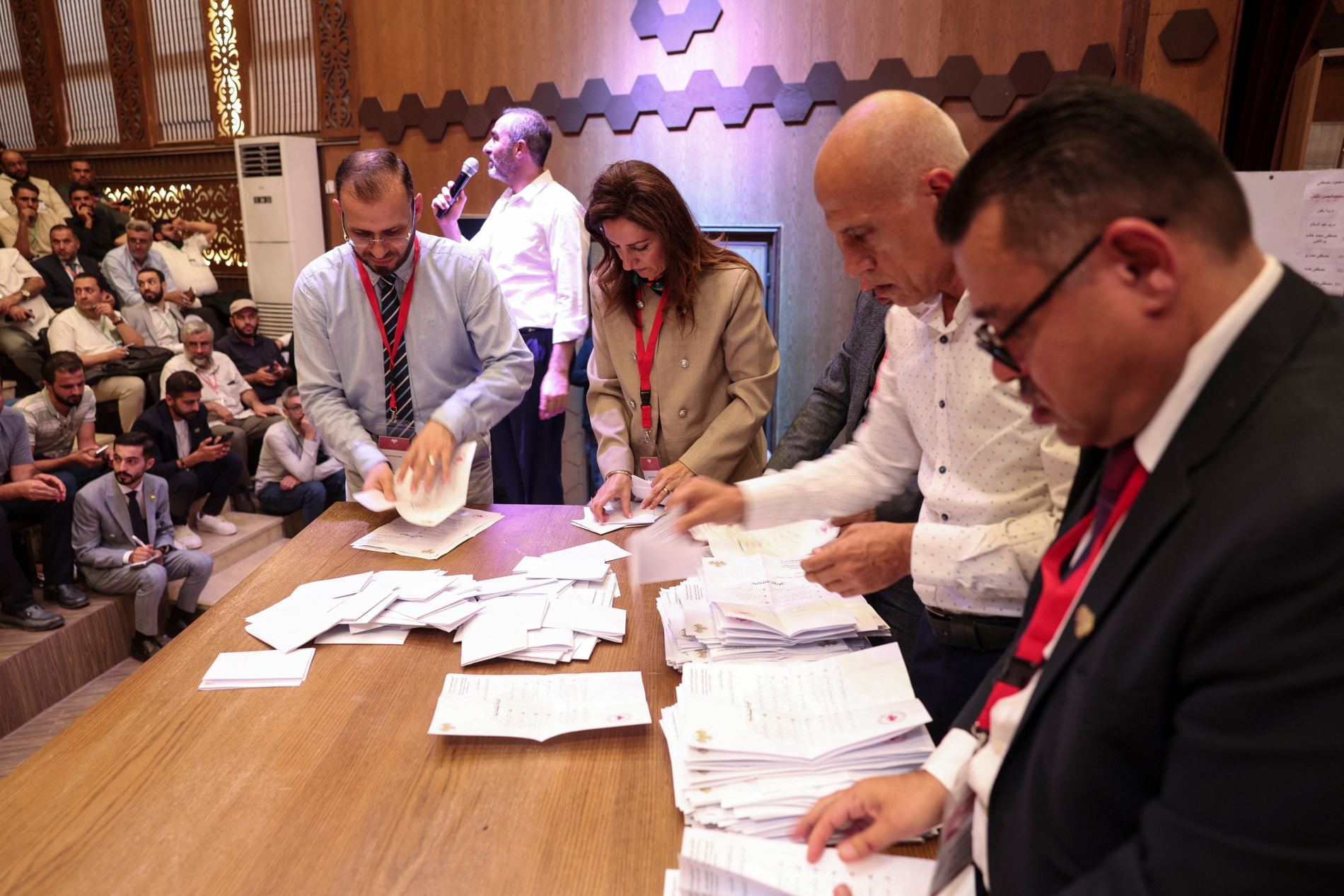

Syria has announced the results of its first parliamentary election since the ouster of former President Bashar al-Assad, with most new members of the People’s Assembly being Sunni Muslims and males.

Electoral commission spokesperson Nawar Najmeh held a press conference on Monday, revealing that 4% of the 119 members selected in the indirect vote were women and only two Christians were among the winners, sparking concerns about inclusivity and fairness.

On 5 October, elections were held in 52 of Syria’s 60 electoral districts. The remaining members of the People’s Assembly will be appointed by President Ahmed al-Sharaa. According to Al Majalla sources, al-Sharaa is expected to announce his list of MPs within 10 days of the election results being released. The idea of his list is to maintain balance, especially in relation to the representation of women, notables, skilled individuals, people with disabilities, and war-injured citizens.

Eight districts, including Ain al-Arab in Aleppo, three districts in al-Hasakah, one in Raqqa, and three in Sweida, had their elections suspended until agreements can be reached between the Syrian state and the forces in control of those areas.

Selection process

The selection process went as follows: a Supreme Electoral Commission (SEC) formed subcommittees across each province. These were tasked with selecting the electoral body, which in turn would elect MPs from within its own members. In order to ensure procedural integrity—from the appointment of subcommittees to the execution of the vote—the SEC coordinated with the Syrian Ministry of Justice to establish specialised appeals committees.

These bodies were responsible for reviewing challenges to ensure fair selection and voting processes. The appeals committee, whose decisions are based on appeals submitted by Syrians, is an independent entity whose rulings are binding on the SEC. If the appeals committee decides to exclude a member of the electoral body due to failure to meet the commission’s criteria, the SEC cannot contest that decision.

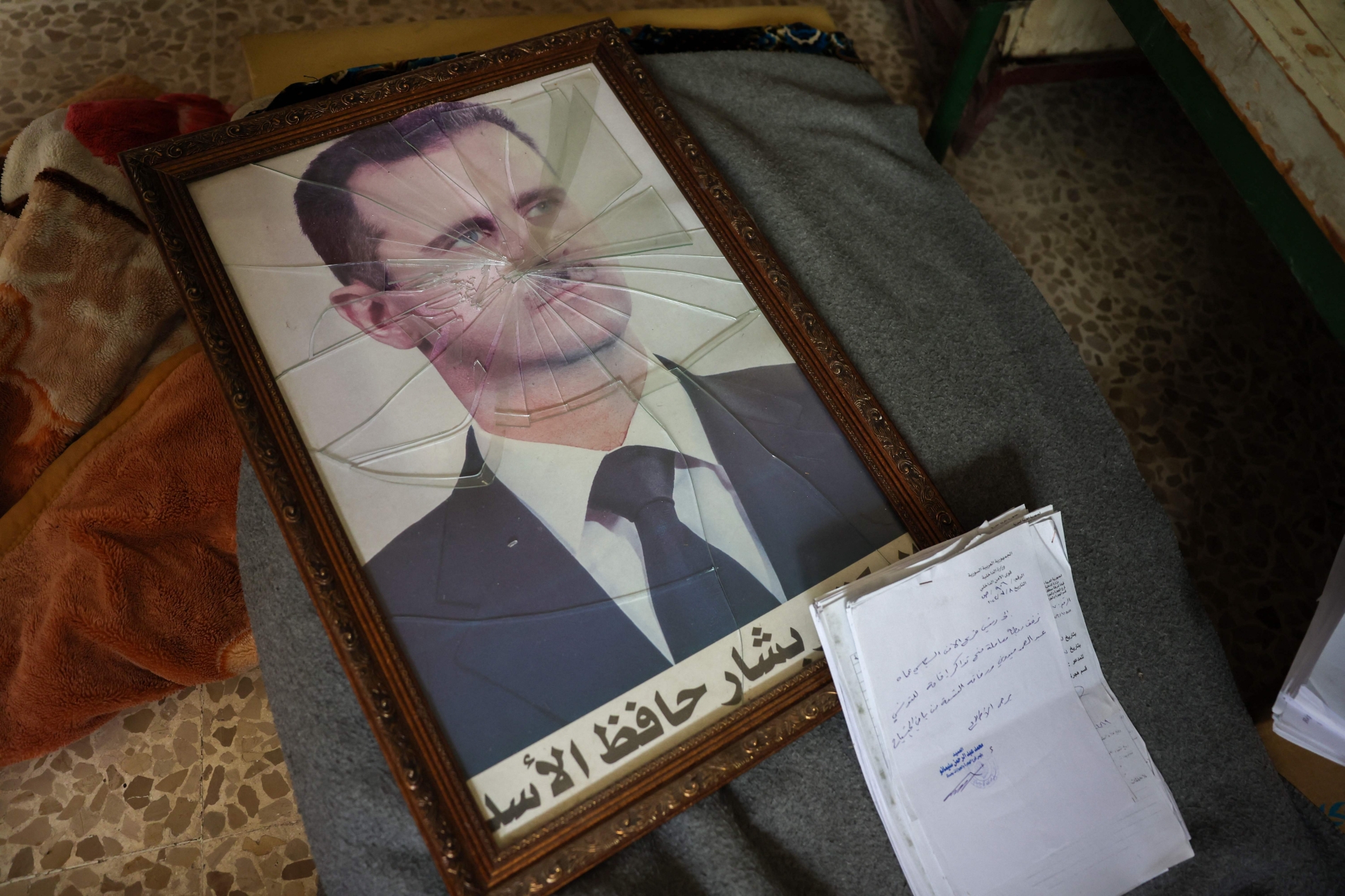

The appeals committee has occasionally based its rulings on public sentiment. In multiple instances, according to Al Majalla sources, individuals were excluded without formal complaints being filed against them, especially when evidence surfaced of their support for the Assad regime. Local populations refrained from submitting formal objections out of fear of reprisal.

Each governorate’s share of parliamentary representation reflects its proportion of Syria’s population, using the 2011 census as a benchmark. For example, if a governorate accounted for 5% of Syria’s population, it would be allocated 5% of the two-thirds of MPs elected under the supervision of the SEC—roughly equivalent to seven parliamentarians.

The 2011 census was adopted as the reference point due to the impossibility of conducting reliable population counts since then, given the vast displacement, forced migration, and refugee exodus that have altered the country’s demographic map. These conditions have rendered any accurate census currently unfeasible.

Despite the historical absence of general elections, officials involved in the process argue that Syrians have played an active role from the outset. When the subcommittees were announced, Syrians could file objections. Once these committees were finalised, they proceeded to select the electoral body, which was also subject to public challenge. According to several members of the SEC, this mechanism has allowed for at least two key stages of citizen participation during the election of MPs to the People's Assembly.

Criticism and anger

The steps taken by the SEC sparked significant public criticism and anger, especially after the final list of the electoral body was released following the appeals period. The list excluded individuals against whom no formal objections had been filed, causing considerable embarrassment for those individuals. It was publicly understood that the finalised list excluded only those who had breached the regulations or had been formally challenged. The SEC’s efforts to calm public discontent by asserting that removals were not based on objections or personal histories failed to ease tensions.

A subcommittee consisting of at least three members serves each electoral district. In larger districts, the number of subcommittee members increases by one for every 200,000 residents. The baseline of three members from varied backgrounds prevents bias in the selection and evaluation process, particularly in governorates characterised by religious and ethnic diversity. Subcommittee members are prohibited from standing for Parliament, as they serve as official representatives of the SEC within their districts.

The commission implemented a coordination mechanism granting subcommittees operational independence. Each subcommittee liaises directly with the SEC, without interaction with other subcommittees within the same governorate. This separation aims to limit undue influence or pressure between subcommittees, particularly in cases where one might be more dominant than another.

Although subcommittees were tasked with compiling the electoral body, there was no standardised or transparent selection mechanism beyond ensuring that candidates met the conditions set by the SEC. While this level of authority can, in theory, promote transparency, it also presents a structural vulnerability.

Individuals have often selected candidates from their own backgrounds—a risk that is particularly pronounced in smaller, homogeneous communities. This dynamic could foster alliances around a particular candidate, aiming to secure their seat in what would be Syria’s first Parliament since the fall of Bashar al-Assad.

The SEC released the subcommittees’ lists without interference, inviting Syrians to file objections against individuals suspected of supporting al-Assad, engaging in corruption, or being involved in crimes or abuses against citizens. Other grounds for objection included age, academic qualifications, and eligibility to represent the nominated district.

Issues emerged when the final list excluded individuals with no record of violations. At the same time, names from the so-called ‘compensatory list’—intended to fill potential gaps in the electoral bodies after appeals—were added.

The SEC defended the removals, stating they were not due to violations but were part of an effort to rebalance the electoral body, particularly in districts suffering from over- or underrepresentation. In response to public outrage in several areas, some subcommittees reinstated previously removed names while excluding others. This attempt to appease the public raised questions about the criteria used for these adjustments and whether such actions compromised the transparency of both the commission and the subcommittees.

According to Al Majalla sources, even subcommittee members were surprised to find names excluded from the final list without clear justification or official complaints. Some submitted legal petitions to the SEC, which sought to mediate what had become an internal subcommittee dispute.