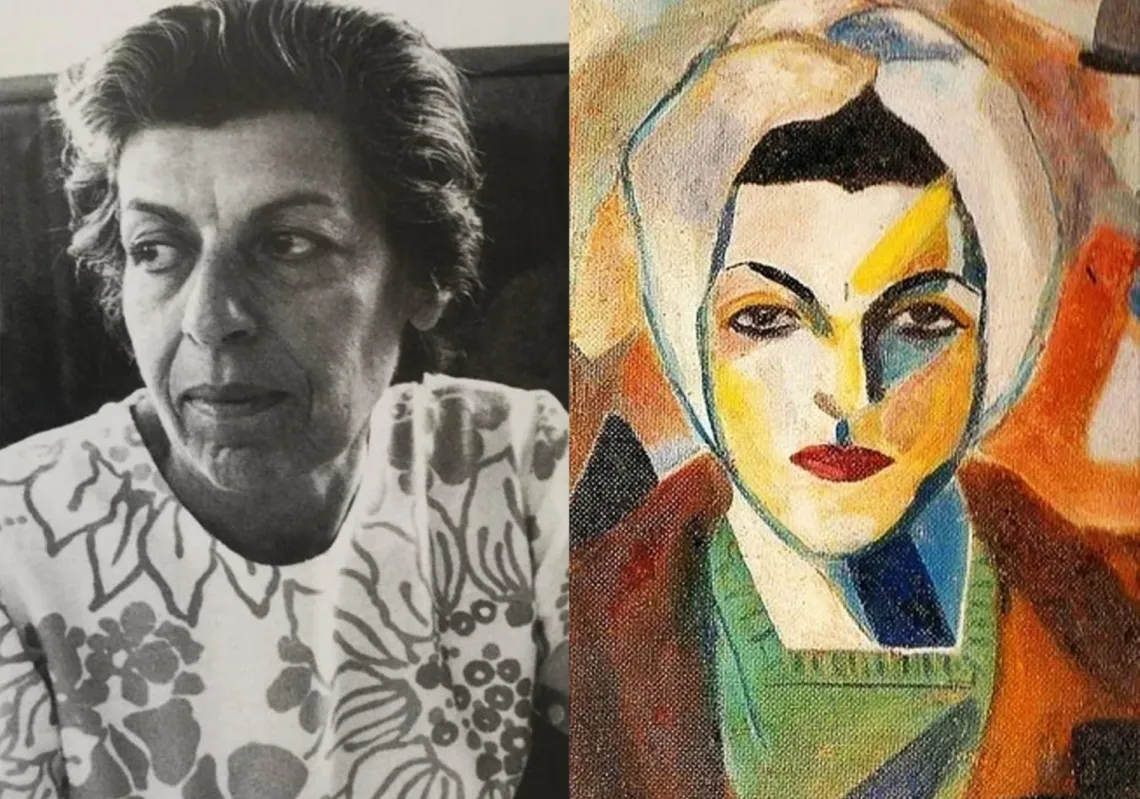

A Lebanese artist of Armenian descent, Maral Dir Bogosian, began her artistic journey in Beirut—a city in perpetual transformation, constantly shifting yet weighed down by crises. Painting her city has both preserved memory and transcended the grief of those raised in Lebanon’s seemingly never-ending wars, which came to be regarded as their fate. For Dir Bogosian, Beirut’s outward features may have changed considerably, yet it retains a fundamental tension between sorrow and joy, war and peace, as though this very contrast were the city’s defining essence. From this premise, her work has flowed.

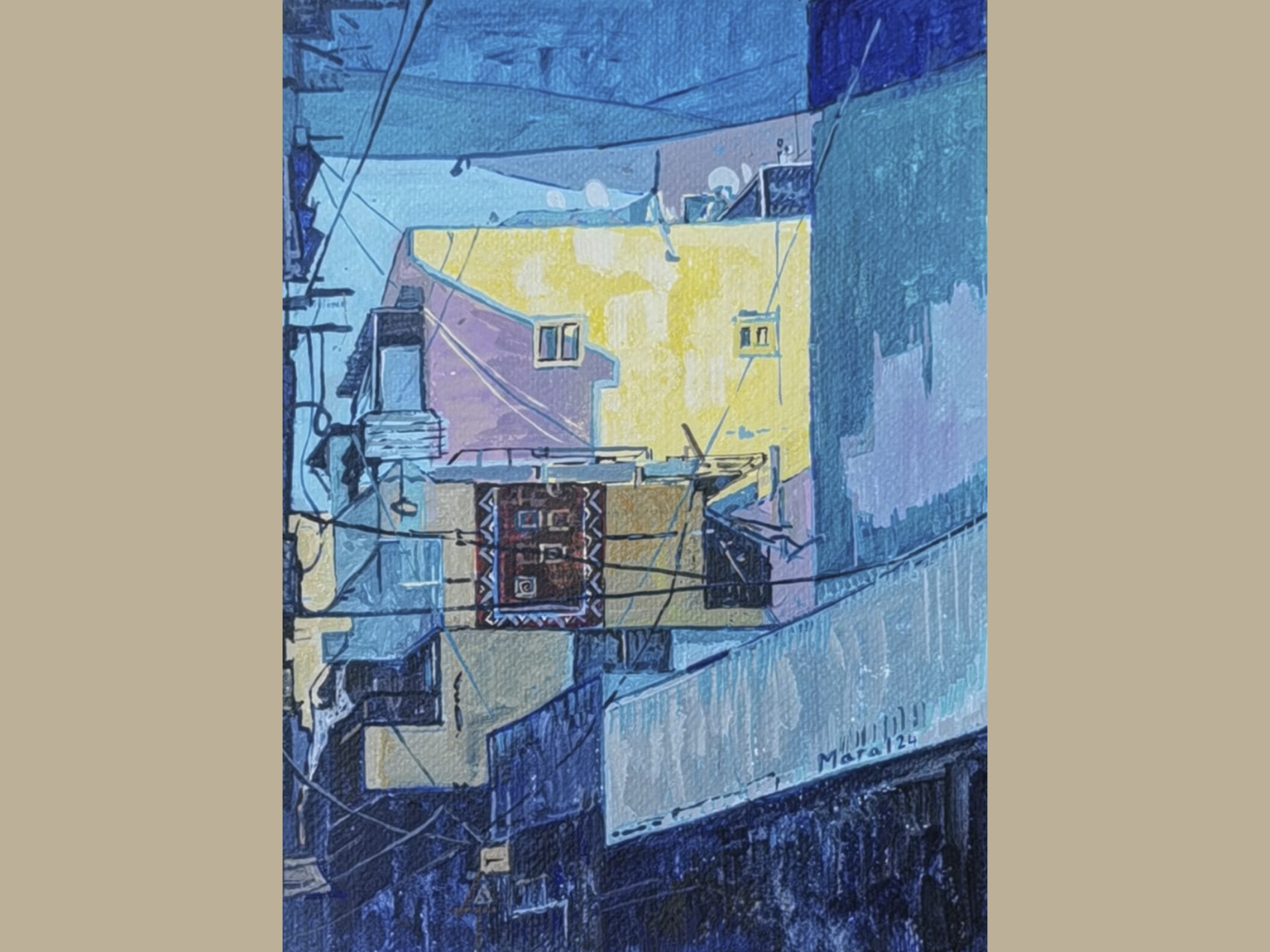

Her latest exhibition, Roofs of the City, shows how she continues to absorb Beirut’s abundant imagery as if encountering it for the first time—with astonishment, affection, and a desire to capture fleeting moments. She increasingly incorporates the sky into her visual language, not merely as a natural element, but as a narrator of the city’s condition and, one might say, its very breath. Sometimes the sky appears to transform into something resembling curtains or veils. In one painting, the veils take the shape of sails, one of several visual metaphors that quietly permeate her compositions.

As the sun sets

This isn't her first rodeo. Maral's first exhibition was held at the city’s Goethe Institute in 2002. Ever since, has been exhibited elsewhere in Beirut, including the Cilicia Museum and the Alwane Gallery.

Art is in her blood: her mother was a sculptor, and her uncle and father were painters (her father specialising in landscapes). Yet for Maral, there can appear to be a sadness in her work. She strives to offset this, such as through a flock of birds, heading once more into that all-important sky.

“The urban landscape holds profound significance for me,” she says, speaking to Al Majalla. “I am a daughter of the city, and I never left it, even during its darkest moments. Nearly every day, just before the sun begins to set, a different kind of time emerges. It is a time I inhabit fully, one that opens doors to a world of beautiful memories formed before the Lebanese Civil War. Among the most cherished are the joyful gatherings of both immediate and extended family.

“This time of day—dusk—marks the end of the daily rush for many. It is distinct from the night, signalling a return home and a moment of rest. For me, it is the hour I dedicate to painting. I focus on the streets and neighbourhoods that surround me. I often find myself depicting countless balconies with no one seated, windows with no passers-by beneath, and homes abandoned by their owners. Yet these spaces do not convey sadness. Instead, they suggest a life that remains hidden.

“There is a great deal of emptiness on the surface, but that does not erase the hope and joy I continue to feel. Despite the country’s tragedies and my own personal losses caused by war, I have managed to preserve these emotions.” Maral speaks of the joy she has sought to infuse into her canvases, describing it as an act of salvation in a country where war “does not seem to have an end”.

Twilight hours have long held a special place in the hearts of artists. The hour before sunset, aka the “golden hour,” is when light gently shapes shadows, softens outlines, highlights features, and draws elements close. Here, the boundary between joy and sorrow can seem to dissolve, between joy-tinged sorrow or sorrow-tinged joy. The purpose of the art is to resonate.

Details of a city

In Maral's canvases, blue is prominent throughout her paintings. The colour is both nostalgic and yet can also bring joy. In part, it depends on the viewer’s openness to receiving it. Elsewhere, the blue can convey a stillness that borders on paralysis. This is moodier and subdued, a wistful blue even when placed alongside other colours that the artist employs skillfully, such as orange, pink, and mustard yellow.

Her art incorporates visual elements unique to Beirut, details that speak to the lives of its residents and their capacity to keep going, whether they be the tangled electrical wires strung between buildings, or the power generators, satellite dishes, rooftop water tanks, and laundry hung on lines outside windows. "The clustered buildings, the abundance of windows and balconies, and the rooftops crowded with satellite dishes and criss-crossing electrical wires, these are details I love to paint because they are part of the city's identity," she says.

"More than ever, I focus on courtyards and the spaces between buildings, however narrow they may be. I am especially drawn to the city's suburbs: vibrant, densely populated, and far removed from its more affluent areas. These are the places that truly reflect the reality of Lebanese life, full of energy and shaped by the ingenuity of people continually devising ways to secure water and electricity."