A prominent voice within Egypt’s ‘Nineties Generation’, the novelist and short story writer May Telmissany has explored the themes of exile, loss, memory, and the female experience throughout her literary career. Her four novels—Dunyazad, Heliopolis, A Capella, and Everyone Says I Love You—have brought her critical acclaim, as have her memoir, A Walled Paradise, and three collections of short stories.

Born in Cairo in 1965, Telmissany is a professor of Arabic and Film Studies at the University of Ottawa and has lived in Canada since 1998. Also known for her work as a translator and film critic, alongside her literary criticism, she was awarded the French Ordre des Arts et des Lettres with the rank of knight in 2021 in recognition of her contributions to culture, the arts, and literature.

Her first novel, Dunyazad, explored themes of motherhood and loss and was translated into eight languages, winning the 2001 Arte Mare Award for the best first novel in the Mediterranean. Her most recent novel, Everyone Says I Love You, was long-listed for the 2023 International Prize for Arabic Fiction.

Here, she speaks to Al Majalla.

What drives you to write?

Writing is the primary force that sustains my life. I wake each day to write, not always literature in its purest sense, but the act of recording and reflecting has become one of my most cherished daily rituals. Perhaps it is a way to resist the monotony of the everyday, a means of filling time, or even transcending it.

I long for an unknown reader, in Arabic or another language, to encounter my words and feel them resonate in heart or mind. I hope that one day a woman might find solace or meaning in what I write. For me, writing is an act of resistance against the ugliness of the world. Yet, over time, it has become more than resistance: it is now a daily practice, interwoven with life itself and inseparable from it.

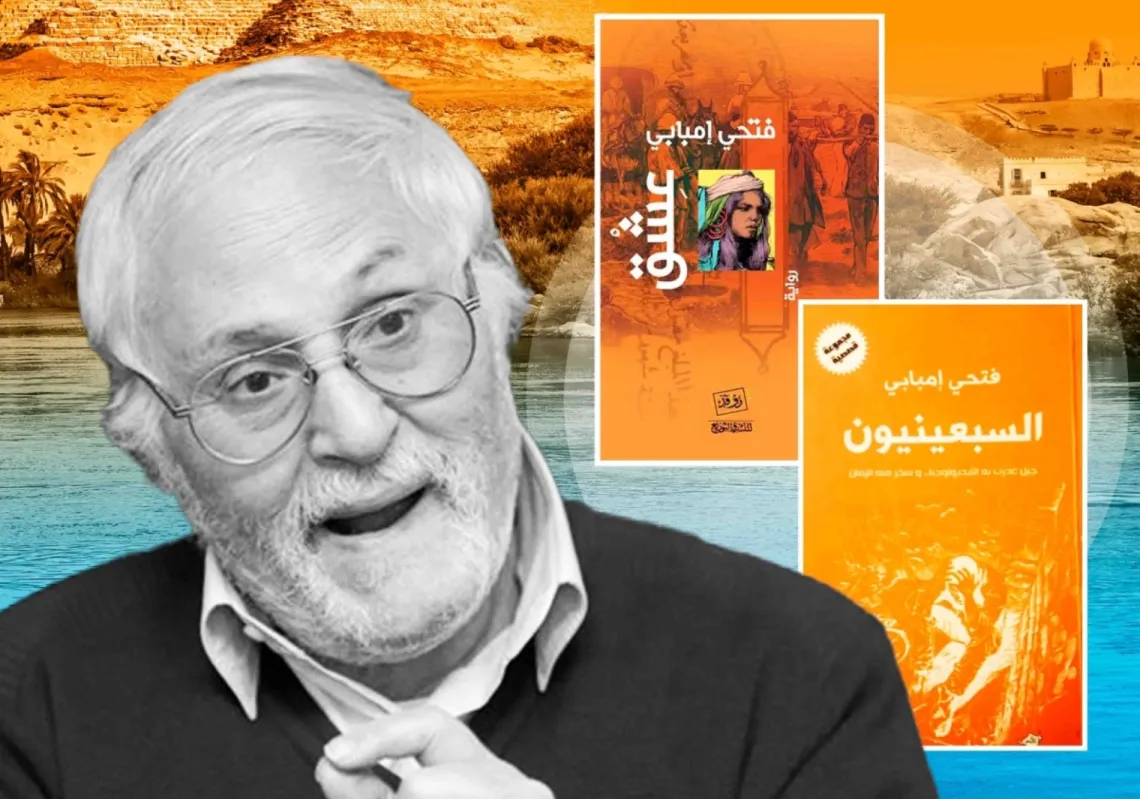

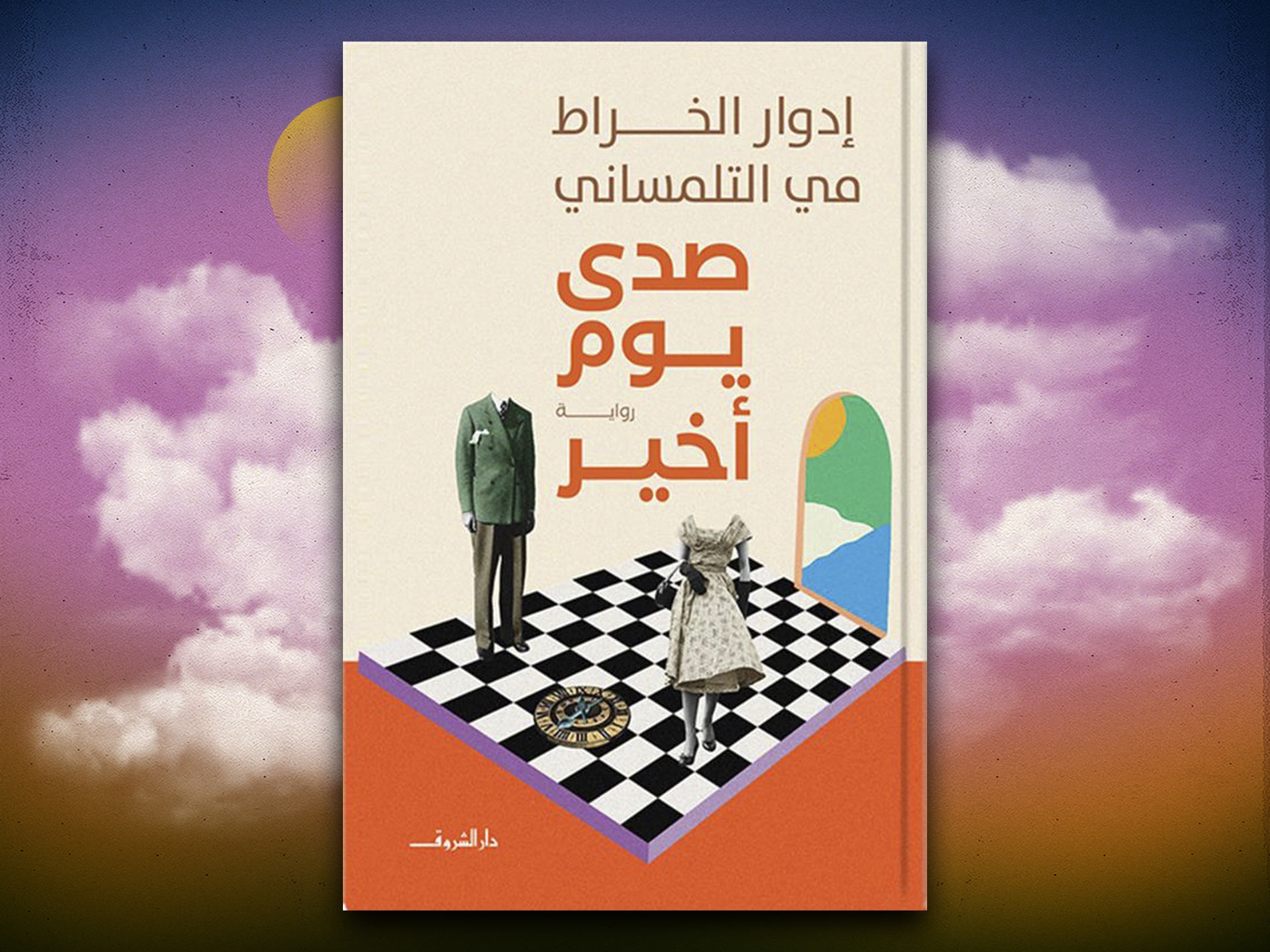

Echo of a Last Day was a collaborative work between you and the late Egyptian novelist and critic Edwar al-Kharrat. Could you tell us about the novel and the circumstances of its creation?

The project was a joint literary experiment proposed by Sayidaty magazine. I accepted because the publisher at the time, the writer Hadia Saeed, told me that Edwar had specifically requested to work with me. After the book was eventually published by Dar El Shorouk, our mutual friend, the poet Jamal al-Qassas, told me he and Edwar had discussed this idea before it reached me. The novel was serialised in Sayidaty, but the manuscript was misplaced for years until I recovered it and arranged its publication.

Why did al-Kharrat not raise the idea of writing the book with you himself?

Perhaps because of my emigration to Canada. We saw each other during my annual visits to Cairo, but in those years, 2000 and 2001, we had no easy way of communicating internationally. The first instalment reached me via fax from Sayidaty, followed by others, until six chapters were published over six months.

I think Edwar saw it as a kind of game between two writers from different generations. At the time, I didn’t know the instalments were based on a short story he had already written and perhaps wished to expand through our dialogue. I never fully understood his exact motivations, as we did not speak directly during the writing or publication. But I am certain he offered me a singular and remarkable experience—an experience for which I remain deeply grateful.