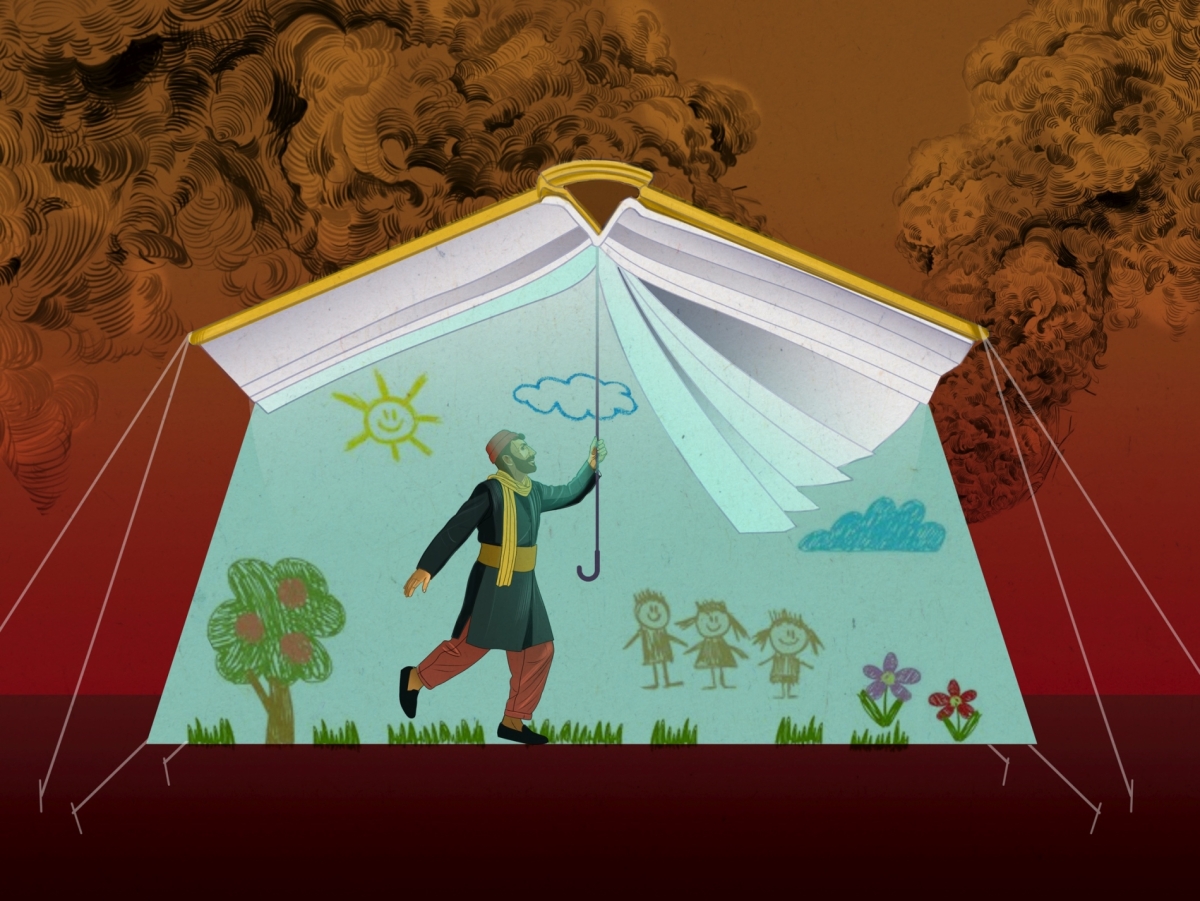

In Gaza, stories are told not merely for amusement but as acts of survival, fragile bridges to a life that drifts further away with each passing day. The hakawati (traditional Arabic storyteller) is not simply the familiar figure in a cloak, nor a woman seated among children with a reassuring laugh and animated gestures.

Here, the hakawati is a deliberate creation: inventive, bold, stories aimed at resisting erasure. Storytelling becomes a way to soften the bite of bombs and starvation, if only modestly. It is not a book of enchanted characters, nor a mythical peace-bringer who slips into a battlefield from a world of calm.

It is a person who inhales the smoke of bombardment, walks for kilometres beneath the burning sun, or threads through dusty alleys between tents to reach a group of terrified children whose eyes hold images they should never have seen. In a genocide, the hakawati changes from a folkloric figure passed down through generations into a lifeline grasping at a childhood that slips away like sand between fingers.

A form of learning

“Gathering children in these conditions is harsh and extraordinary, unlike anything before,” says Ashjan Abou Obeidallah, a hakawati and artist working amid displacement, hunger, and loss. Speaking to Al Majalla, she describes a process that begins long before the first words of a tale are spoken.

The children arrive through shelter committees. She collects them, arranges the sessions, and makes her way to the venue with the help of her local organisation, which tries to offer these young ones a form of community education. Everything remains precarious. The children arrive weighed down by fatigue and grief.

One has just carried heavy gallons of water from a distant source, while another weeps silently for a father lost in the latest airstrike. Their bodies are thin, their stomachs empty, their minds torn between memories of demolished homes and the long queue outside the soup kitchen. Obeidallah says the genocide has reshaped their inner worlds.

“Before the war, we told children stories about their dreams, their ambitions, their sense of self. A child could sail through a tale as easily as they could drift into their own imagination. Now everything is different. We begin with talk of explosives, landmines, and suspicious objects—these have become part of daily life, and the stories have turned into warnings against death.”

Looking up at the sky, she continues. “Imagination has shrunk, shrunk terribly. The genocide has stolen Gaza’s children’s ability to dream, confining their minds to a grim reality of hauling water, enduring hunger, lacking clothing, and living within a catastrophe that devours our days.”

Creating other worlds

Mohammed al-Aamoudi, another hakawati in Gaza, sees it differently. “A child’s identity is built on imagination, even in the harshest conditions. I still see it pulsing in them, perhaps as an act of defiance. They hold inner conversations, create alternative worlds, and escape into them when there is no other way out.”

Abu Obeidallah says: “When we ask about their dreams, the answers are heartbreaking. How can we dream when the genocide is not over? How can we dream when we are hungry?” Here is a contrast: between al-Aamoudi’s belief in the persistence of imagination, and Abu Obeidallah’s conviction of its erosion.

At least 17,000 Palestinian children have been killed in this genocide. Storytelling no longer revolves around fables that end with moral lessons, but to survival skills, personal hygiene, recognising suspicious objects, evacuating safely, and adjusting to life in tents. Most of these circles have lost their clothes under the rubble. They arrive day after day in the same soiled garments, with no way to wash them.

“The shame of dirty clothes crushes a child’s spirit,” says Abu Obeidallah. “They grow withdrawn, distant from the group.” Lice infestations made worse by overcrowding and poor sanitation can disrupt the gatherings. “Sometimes we have to keep children apart to stop infections from spreading,” al-Aamoudi explains.