“Isn’t there, in every passing second of life, someone laughing? Then on this earth, laughter is unceasing.” So wrote Ziad Rahbani, son of the iconic singer Fairuz, in My Friend God in 1971, written at the outset of his creative journey. That journey sadly ended in a reported heart attack last week.

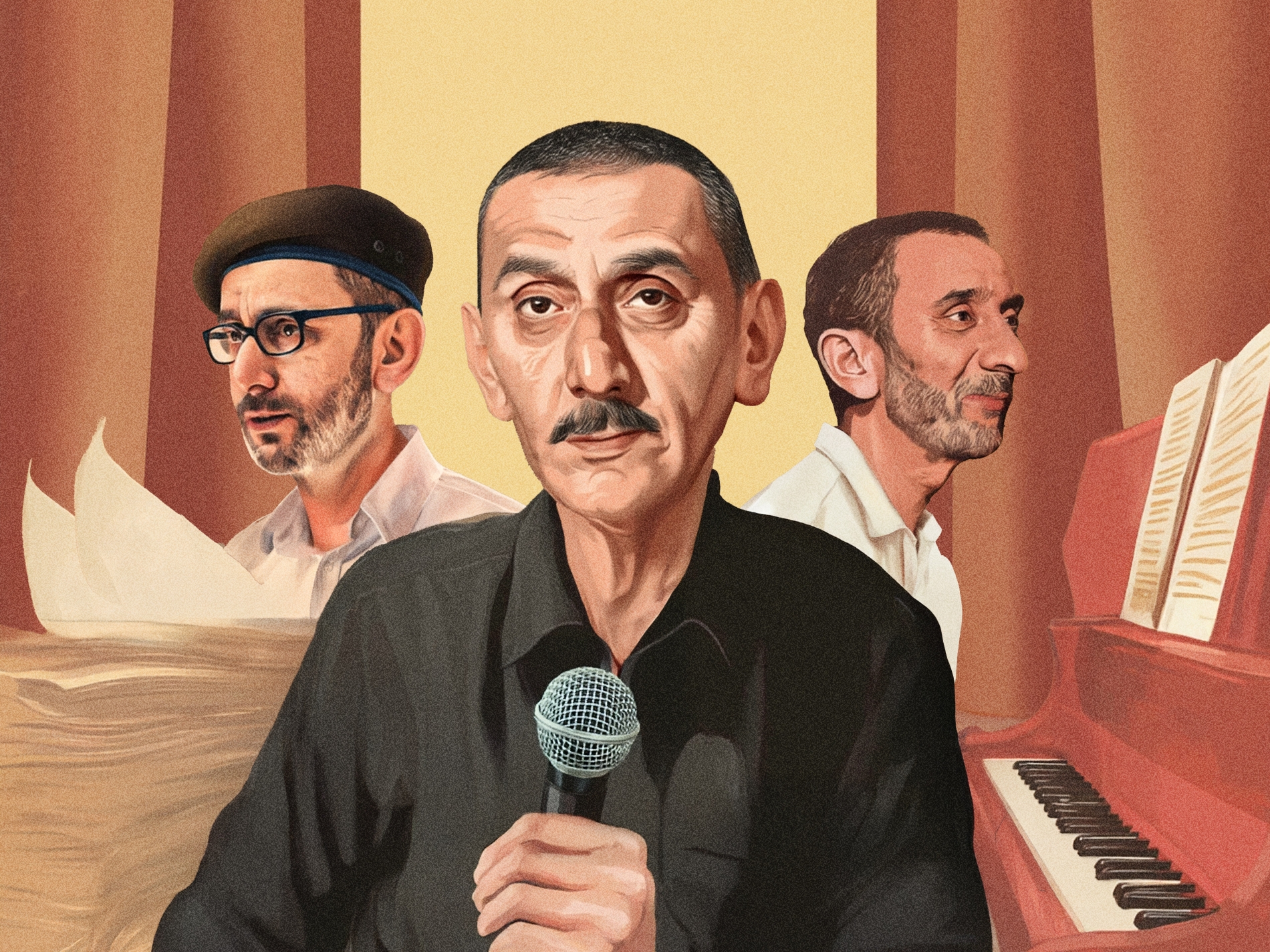

His was an influence, a uniqueness, and an indelible presence in Lebanon’s artistic, social, and political spheres. Heir to the Rahbani legacy, he was frequently labelled as a “genius,” a label he hated. Though this was more of a burden than an accolade, it was nevertheless inescapable. For how else might one define an experience so rich, layered, and boundless in scope? Ziad Rahbani was never merely a musician, nor merely a poet, playwright, (dark) comedian, political commentator, or social critic. He was all of these, simultaneously. Beyond that, he was the son of the venerable Rahbani dynasty, a custodian of its legacy and—paradoxically—its gentle rebel.

Generational spokesman

Ziad Rahbani’s brilliance in music, theatre, and beyond is often attributed to innate talent, as though it were embedded in his very being from birth. One commentator even said it was in his genes, inherited from his father, Assi Rahbani, and his mother, Fairuz. Those whose artistic and political leanings are fundamentally at odds with Rahbani’s may want to reduce his experience to a kind of populist shorthand that—whether out of ignorance or the reverence that often accompanies death—avoids any serious attempt to define the specific contours of his oeuvre, retreating instead into the safety of sweeping, unexamined generalisations.

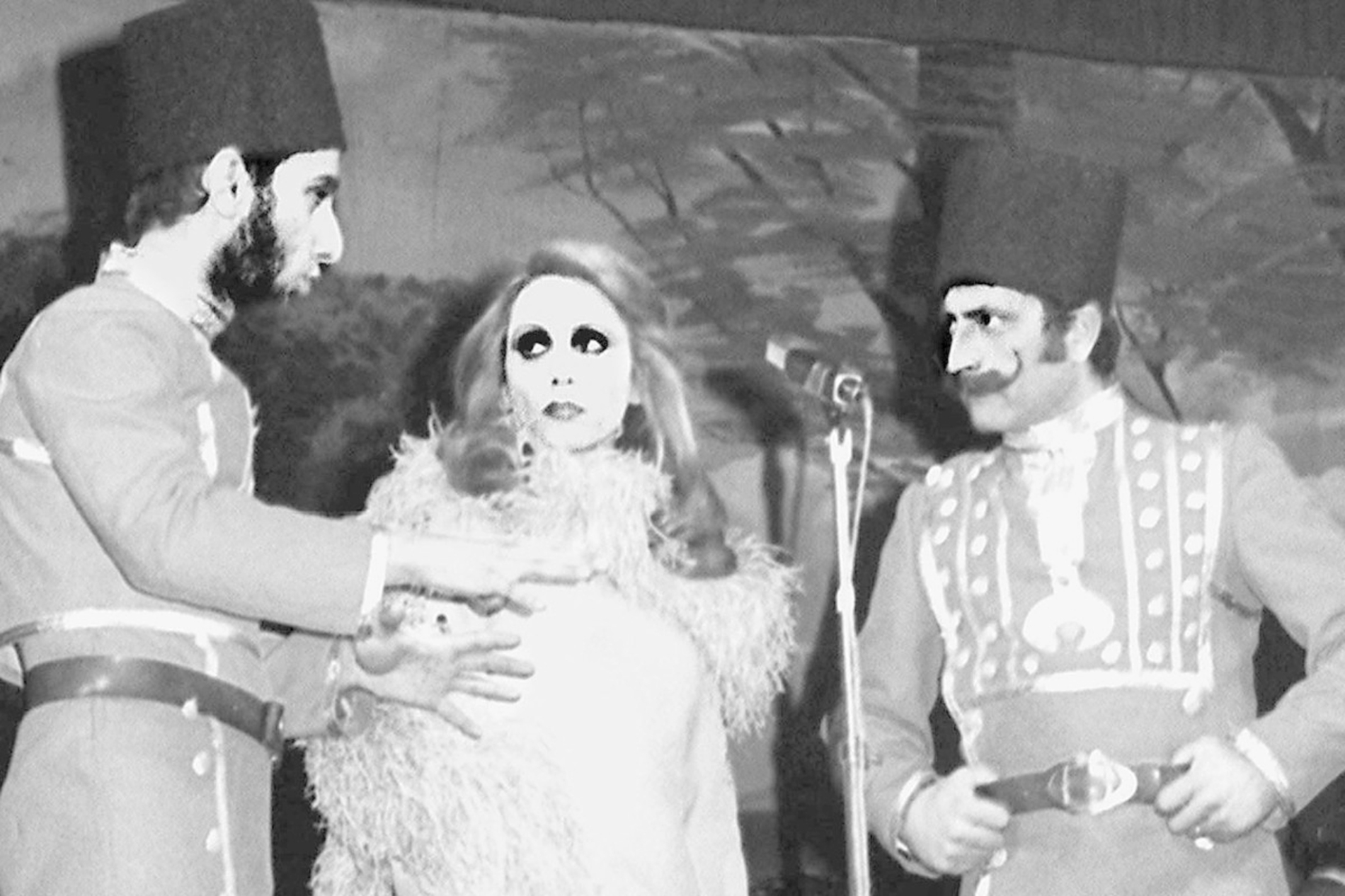

More significantly, the collective farewell to Rahbani, who was claimed by everyone and by no-one, tends to obscure a key dimension of his career: the profoundly collaborative nature of his work. Despite his striking individuality, at its core his journey was a collective endeavour, shaped and matured through a group dynamic. Ziad Rahbani was not simply a voice for a swathe of his generation; he was a living embodiment of it, born of its aspirations, dreams, contradictions, and its diverse creative talents.

Collective effort

In the farewell to Ziad, echoes could be heard of the sentiments expressed upon the deaths of his father, Assi, and uncle Mansour, aka ‘The Rahbani Brothers.’ Like Ziad, their work was shaped and enriched by dozens of poets, journalists, musicians, playwrights, filmmakers, and political activists, yet their legacy—like Ziad’s—was also distilled into the singular label ‘genius,’ a mantle that Ziad was always destined to inherit after his father’s death, just as he was equally compelled to bear the iconic stature of his mother, who held legendary status across the Arab world.