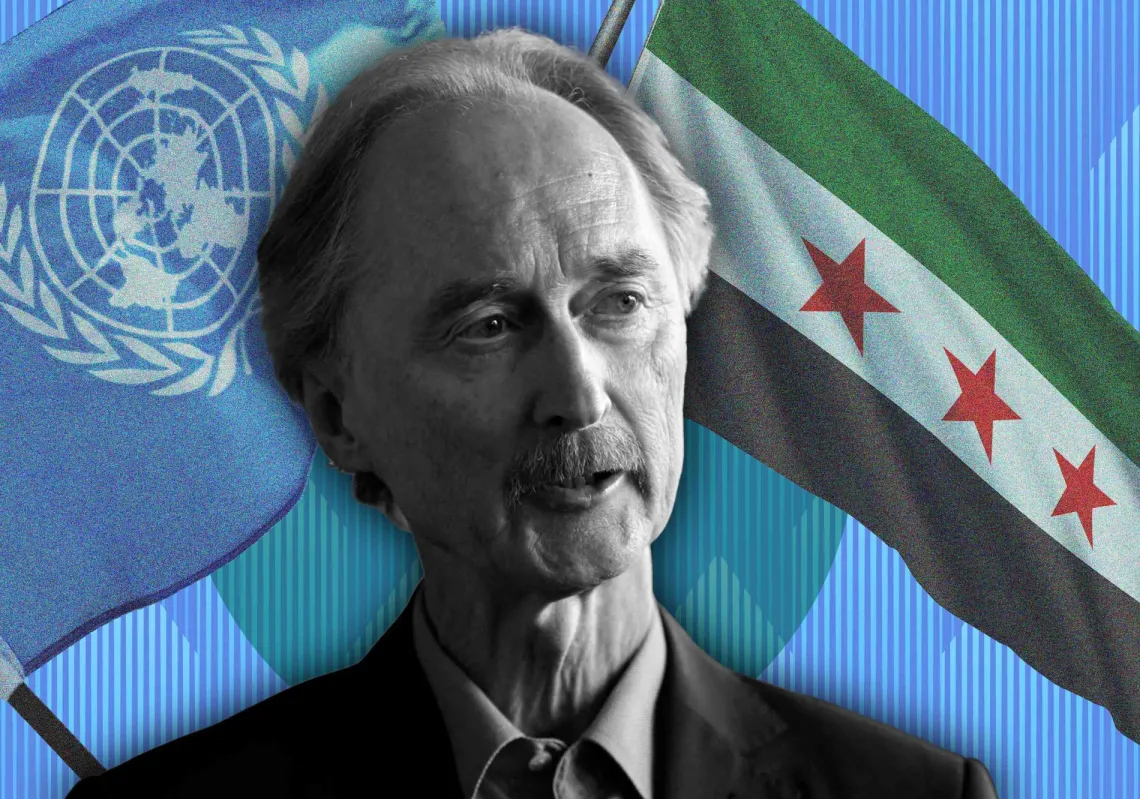

For 40 years, Martin Griffiths has been flying into the world’s hotspots and trouble zones, speaking to those deemed unpalatable, trying to make peace work, and establishing off-radar connections, all the while learning lessons along the way.

A prominent British authority on the Middle East, he has served as the UN’s Special Envoy to Yemen, during which he met Houthi and Iranian leaders—all water off a duck’s back for someone who began their career dealing with the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia.

Although he stepped down for health reasons last year, his tenure as UN Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs placed him at the heart of major global crises, addressing some of the world’s most complex humanitarian emergencies.

In a wide-ranging interview with Al Majalla, conducted on 10 July, after the 12 Day War between Israel and Iran, he offered a sweeping assessment of the region’s shifting landscape encompassing Gaza, Israel, Syria, Lebanon, Yemen, and Iran. Here is the conversation:

__

How do you see the Middle East after the 12-day War between Israel and Iran?

I’m not sure it’s now a safer Middle East, despite all the claims. There are so many claims and counter-claims about the nuclear project in Iran, I’m not sure we know the truth as to whether it’s been set back or not. There’s a possible ‘convergence of interests’ here, to keep quiet, because it’s good to create a ‘win’—the US and Israel love getting that ‘win’.

Iran presumably wants to keep it in the shadows, because they don’t want to be bombed again in case it (the US/Israeli bombing in June) didn’t actually succeed, and even the Pentagon said it didn’t, let alone the IAEA (International Atomic Energy Agency). If that’s true, which I’m sure it is in different ways, then we are in trouble, because, as you know, this is not just about Iran; it is about the region, with so many divergent interests.

Are we back to a shadow war, or will direct Israel-Iran confrontation remain?

That’s a central question not being asked enough. There are two alternatives, but they aren’t black-and-white. Broadly speaking, one version recognises that there is a mutual interest between the parties to ‘make good about it,’ despite the truth to the contrary. The other is that President Trump and (Israeli Prime Minister) Benjamin Netanyahu return to bombing if they see progress in the nuclear project.

In that sense, I’m not clear whether the enforced absence of the IAEA is a convenience, because I believe they (the IAEA) will tell us the truth. For me, there’s a question as to why they’ve been excluded. So, despite all the ambiguities and opacity of this ceasefire, and despite it being obviously welcome, we don’t know which of these two roads will be taken. Will it be a stabilising moment for the region, or will it be a moment to encourage further domination of the region?

Do you think a New Middle East is emerging out of this?

All the books we’ve read about grand plans, the grand compact, the future... History is always full of these grandiose schemes, isn’t it? I didn’t believe them about the Middle East, although I’ve been seduced by them, by specific ideas. The Abraham Accords is just the latest, isn’t it?

I’m unconvinced by the notion that there is suddenly a clear blue sky, that now there will be a whole new sense of companionship and leadership, and that suddenly all the oppositions and enmities that we’ve seen—and that remain unresolved—will somehow just go away because of this great sweep of power, influenced by Israel, the US, and the European Union, which is clearly on a certain ‘side’.