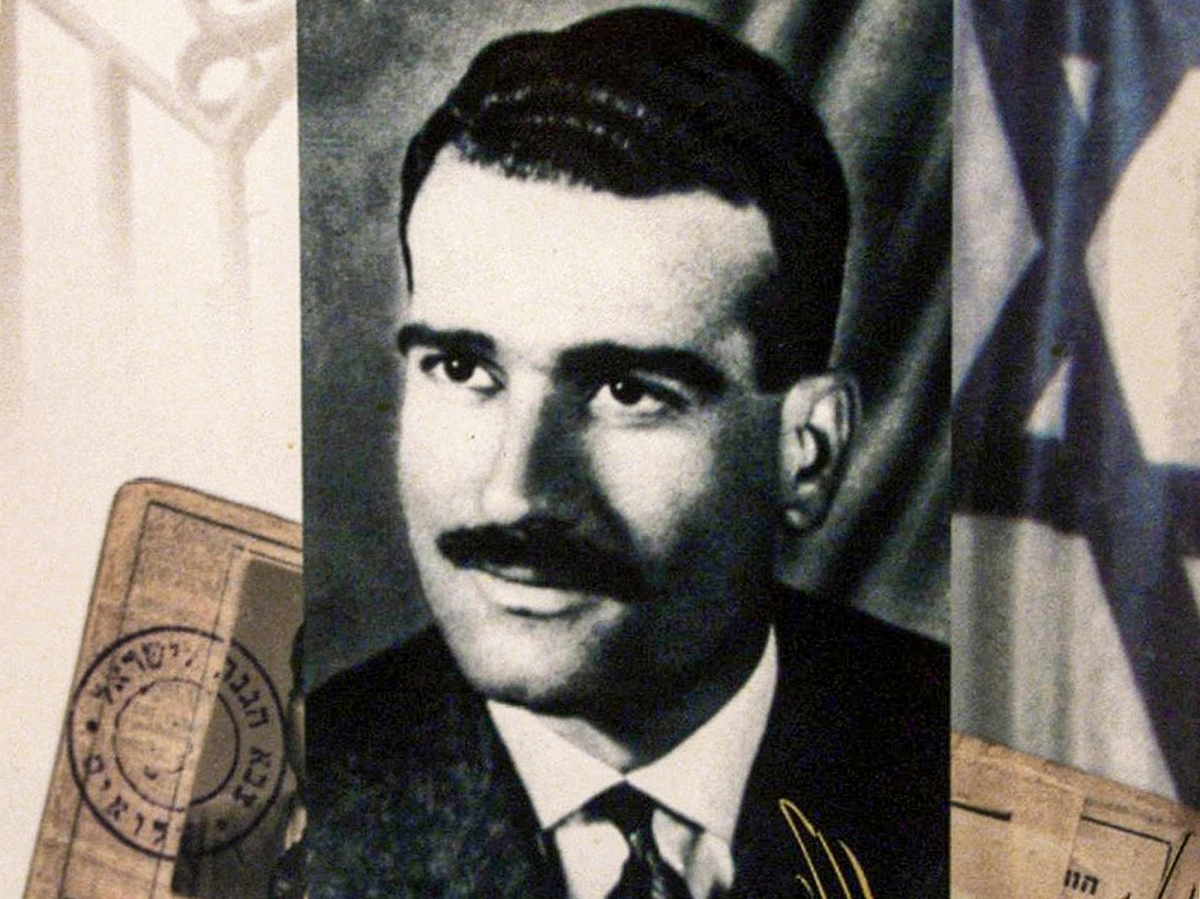

On this day in 1965, Israeli spy Eli Cohen was executed by hanging in Marjeh Square in the heart of downtown Damascus. His execution verdict was pinned to his chest, which was issued "in the name of the Arab people of Syria" as his body remained suspended on the gallows for all to see.

For the ruling Ba'ath regime, which had come to power just two years earlier, it was a seismic event that implicated many of its key figures—chief among them being then-head of state, General Amin al-Hafez. State-directed Syrian media boasted of this major intelligence achievement, although some argued that the Ba'athist state inflated Cohen’s case to project an image of vigilance against domestic and foreign threats. Their argument was that Cohen wasn't the threat that the government claimed him to be, but his execution was an attempt to boost the Ba'ath Party's street credibility.

Meanwhile, others interpreted the incident as greatly damaging to the reputation of Amin al-Hafez, who accused him of being Cohen's personal friend and even went as far as suggesting the president was considering him for a ministerial post in the Ba'ath government. But perhaps the most damaging accusation was that the intelligence gathered by Cohen during his mission in Damascus was among the key contributors to Syria's defeat during the 1967 war.

Less than one week after the sudden collapse of Bashar al-Assad's Ba'athist regime on 8 December 2024, Israel expressed interest in locating Eli Cohen's remains, buried in an unmarked grave since 18 May 1965. Everyone who knew the grave's actual location has since died, like presidents Amin al-Hafez and Hafez al-Assad, or army commanders and defence ministers like Ahmad Suwaydani and Mustafa Tlass.

This was not Israel’s first attempt to find Cohen's remains, and won't be the last. Back in 2021, Tel Aviv sought Russia’s help to find Cohen’s remains in the demolished Palestinian Yarmouk Camp on the outskirts of the Syrian capital. Days after Bashar al-Assad assumed power in 2000, Cohen’s widow, Nadia, appealed to him to help retrieve her husband's grave, but he never responded.

There is only one survivor who might know the answer: Sa'id Jawish, chief of the military unit that raided Cohen's home and had him arrested on 24 January 1965. Jawish was a member of Unit 134, which specialised in wireless communications surveillance and was established in 1960. He might also know the name of the gravedigger who buried Cohen, though it is unlikely Cohen’s body remains in the same soil after six decades. It has probably been moved multiple times since then.

Infamous case

Eli Cohen’s case remains one of the most famous espionage stories in the modern Arab world, though younger generations know of it only through the short 2019 Netflix series or from what has been passed down from one generation to another of Syrians.

Intertwined with that of the early Ba'ath years, Cohen happened to be in Damascus when the Ba'athists came to power on 8 March 1963. An Alexandrian Jew of Aleppine origin, his father emigrated to Egypt in 1914.

Ten years later, Cohen was born and settled in Israel with his family following the 1956 Suez War. He joined Israeli military intelligence and later the Mossad, which prepared him for his special mission to Syria. Sent first to Buenos Aires in 1961 in order to infiltrate the Syrian expatriate community in Argentina, he entered Damascus in February 1962 under the alias Kamal Amin Thaabet, a wealthy Syrian expatriate.

Much has been said about the man who helped him cross the Syrian-Lebanese border; wealthy Damascene businessman Majed Sheikh al-Ard, whom he met on board a ship sailing to Beirut in 1962. Charmed by this well-spoken young man, Sheikh al-Ard helped him enter Syria and rent a furnished apartment on Abu Rummaneh Street, an upscale neighbourhood of new Damascus.

The apartment was owned by Haitham Qotob, an employee of the Central Bank of Syria and scion of a leading Damascene family. That, however, is where the Cohen-Sheikh al-Ard relationship ends, given that the Syrian businessman had no military or political connections in Ba'athist Syria. In other words, he became of little value to the Israeli spy, who among other things, was tracking Nazi fugitives based in Damascus, like high-ranking German officer Alois Brunner, who had entered Syria during the union years with Egypt.

Sheikh al-Ard was arrested after Cohen’s capture and famously refused an offer to escape prison, insisting that he was innocent. Hailing from a prominent feudal family, his arrest was music to the ears of Ba'athist hardliners, who strove to destroy his generation and creed, both economically and politically, and socially as well.

Sheikh al-Ard's arrest happened to come just months after the Ba'athists had ordered their most massive wave of nationalisation decrees on 1 January 1965, targeting hundreds of Damascus businessmen like himself. He was transferred to Palmyra Prison, where he allegedly committed suicide, though many believe his Ba'athist jailers executed him.

Warm welcome

Many Syrians welcomed this wealthy "businessman" coming from Argentina, while Damascus Radio even hosted him on a programme for expatriates, playing Wadih El Safi’s Talu Ahbabna Talu. Cohen built extensive social connections, including military figures and a few Syrian women, but contrary to rumours after his arrest, they were not from the upper crust of Damascus society.

The old elite had been entirely sidelined after the Ba'ath Party coup, making them useless for Eli Cohen. The director of the military court that tried him, Salah al-Din al-Dilli, wrote: "Cohen’s home (in Damascus) was a den of debauchery... His obsession was indulging in pleasures and trips to Zabadani and Ghouta with women who revelled in mischief and vice. He was a legend in depravity." While Cohen did manage to penetrate certain circles of Syrian society, an examination of his televised trial reveals that his friends were second- and third-tier figures.

Among them, for example, was George Seif, a journalist, who gave him a press pass and introduced him to a flight navigator assistant named Eli Almaz. Seif was sentenced to ten years of hard labour; Almaz received six months. Other acquaintances included a municipal affairs employee, a tourism ministry worker, and the son of a journalist from the alKhashn family, who tried arranging Cohen’s marriage to his sister-in-law.

His female friends were flight attendant Haifa Hamdi, high school student Abla Ammar, radio employees Jamila and Amina Sharshouh, and two women from the Zayat family. These were mostly ordinary women seeking marriage with the "wealthy bachelor" Kamal Amin Thaabet, and all were acquitted during the trial.

Trial recordings

Accessing these trial tapes is now difficult, as Syrian TV erased them many years ago to record the lengthy speeches of Hafez al-Assad. The trial itself had been recorded over early Syrian dramas, including the works of Salim Qattaya, a pioneer director and one of the co-founders of Syrian television. Qattaya was killed twice by the Ba'ath: first physically when he suffered a fatal heart attack after Ba'athists stormed the television to hunt down soldiers involved in a botched coup attempt, and the second time morally, when they erased his works from the archive to record Cohen’s trial.

Among Cohen’s friends was the nephew of General Abdul Karim Zahreddine, the army chief during the secessionist period (from Egypt) before his ouster on 8 March 1963. This young Zahreddine was also an officer, and like his uncle, he too was dismissed by the Ba'ath and transferred to a junior post at the Ministry of Rural Affairs.

He would meet with Cohen either at the latter's home or Café al-Kamal, but they stopped meeting after he was dismissed from the army and became of little use to the Israeli spy. Rumours claimed he took Cohen on a tour of the Syrian-Israeli front, providing critical intelligence.

But any intelligence obtained in 1962 had become completely obsolete after the Ba'ath coup of 1963, given that all military positions were changed on the front, and so were field commanders. Military strategies were once again overhauled after Salah Jadid’s 23 February 1966 coup, making Cohen’s 1962 information irrelevant five years later when the 1967 war broke out.

Relationship with Amin al-Hafez

There are claims that Cohen was a good friend of then-president Amin al-Hafez, whom he met in Argentina when Hafez was serving as military attaché in 1962. That relationship was further dramatised and cemented in the Netflix series, although al-Hafez himself spoke to Arab media back in 2001, saying that when he arrived in Argentina, Cohen had already left for Damascus.

Said Jawish confirmed that al-Hafez met Cohen only after the latter's visit in January 1965, never before. According to Jawish’s account, the Syrian president went to the interrogation centre where Cohen was being held and asked him: "You there; what's your name?"

Cohen: Kamel Amin Thabet

Hafez: What do you do in life?

Cohen: I am a Muslim Arab merchant from Argentina.

Hafez: Then recite the Fatiha for us (the first verse in the Holy Quran).

Cohen: In the name of God, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful. Praise be to God ...

He suddenly paused, unable to remember the rest of the verse.

Hafez: Why did you stop?

Confession

Cohen claimed that he forgot the rest, to which al-Hafez snapped: "How can a Muslim at your age not know the Fatiha?" The exchange ended there, and al-Hafez ordered Captain Adnan Tayyara to take Cohen to the basement for interrogation, where he was grilled—and beaten—by an officer named Abdul Qadir al-Jaleel. This is where he confessed under torture, saying: "My name is Eliyahu Cohen, an Egyptian Jew born in Alexandria."

Rumours proliferated, which Amin al-Hafez addressed in a 21 May 1965 interview with Al-Usbu al-Arabi. Speaking to Zouhair al-Mardini, the magazine's bureau chief in Damascus, he said: "We received thousands of telegrams pleading for Cohen’s life... interventions, mediations, and bribes. We smiled at the fabricated stories."

"They said Cohen was friends with Salah al-Bitar (then prime minister and Ba'ath Party co-founder), and he travelled with him to Jordan. They claimed I had known him for years and that he also had close ties to officials. Let them say what they want. The truth is ... I only met Cohen days after his arrest. I personally confronted him in prison during early interrogations."

No photos or records place al-Hafez and Cohen together, giving credence to claims that their friendship was a fabrication by Egyptian media, which was then locked in a propaganda war with Damascus, especially after Nasserists attempted a failed coup on 18 July 1963 and were sent to the gallows by the Ba'ath.

Egyptian and Lebanese press labelled the Ba'ath regime "fascist," leveraging the Cohen case to paint Amin al-Hafez as a Zionist agent. Syrians widely repeated these claims, especially after Hafez’s 1966 ouster and Hafez al-Assad’s 1970 coup, where he lashed out against the early Ba'ath years and its president.