“No one should attempt to play around with this nation, to test the patience of Turkey. As precious as Turkey’s friendship is, so harsh will be her hostility.”

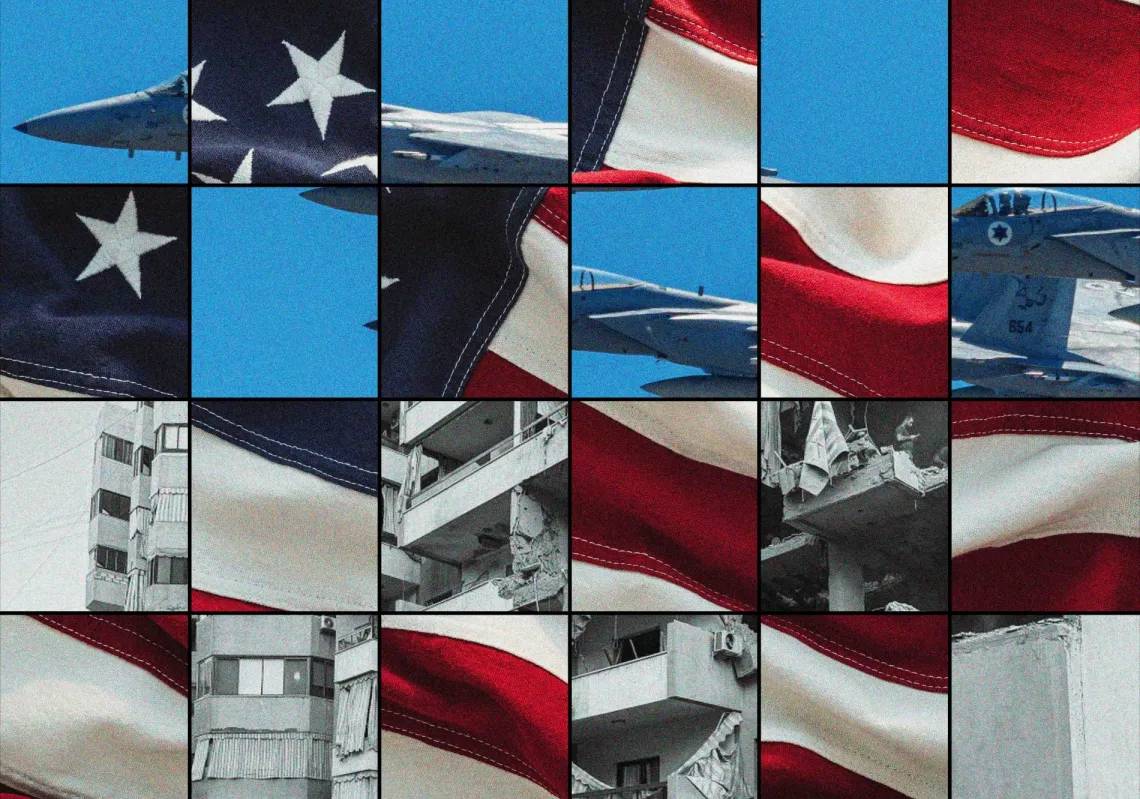

Such was the outburst of an emotional Tayyip Erdogan on 1 June as he responded to the deadly Israeli attack on a Turkish-led flotilla carrying humanitarian aid to Gaza. Erdogan’s speech to the Turkish parliament was intense, blunt and at times even threatening. It felt as if he was giving a subtle answer to that lingering question about his country: The West, it seemed, had finally lost Turkey.

When Erdogan’s newly-founded AKP (Justice and Development Party) took power in an unusually decisive election in 2002, it was not evident that a debate over the country’s “reorientation” would soon ensue. Despite the Islamist roots of its main founders, the AKP had managed to appeal to a broad base. It had campaigned—and won—on a platform that put progress towards EU membership on top of the agenda.

The first sign of trouble came in 2003 when the Turkish parliament stunned the US by refusing to allow US bases in Turkey for the invasion of Iraq. Although a major milestone in the EU membership process—official candidate status—was reached in 2004, the process lost its initial momentum soon thereafter. While full membership remains their stated goal, Turkey’s leaders have been increasingly less hesitant to express their frustration with the EU’s stalling. In 2008, the seeds of the current crisis with Israel—a long time ally—were sown with Israel’s surprise attack on Gaza, which humiliated Turkey by undermining the country’s efforts to broker a backroom peace agreement between Israel and Syria. Mr. Erdogan stormed off a panel in Davos after telling Shimon Peres that Israelis “know very well how to kill.” Only two weeks before the Gaza incident, Turkey and Brazil voted against a UN Security Council resolution to impose sanctions on Iran and instead pushed for a nuclear swap agreement with the isolated country.

It is hard to deny that Turkey today is a very different country than it was 10 years ago. For several reasons, however, many Western observers have misinterpreted this transformation. To begin with, excessive attention is being paid to Mr. Erdogan and the excitement that his populist rhetoric over Gaza has created in the Turkish and Arab street.

Second, perhaps as a legacy of the Manichaeism that George W. Bush attempted to impose on our imagination, Turkey’s role is seen in a strictly binary context. The vision, we are told, is neo-Ottomanism and the goal is to re-establish Turkey as a rival power to the West. Finally, since her allies have failed to create a platform where Turkey can play a new role (other than “eternal applicant to the EU”), the country’s actions are seen to be happening in isolation from her allies.

At this critical juncture, a correct reading of Turkey’s intentions is essential. Turkey’s new stance in foreign policy should be understood by a principle much simpler than a reorientation away from the West: the goal of becoming a regional leader and a prominent global player. While this ambition comes with the demand for a renewed role for Turkey on the international stage, it does not necessitate a reorientation, least of all one that has to happen at the expense of the West.

The real engine behind Turkey’s show of independence, therefore, is not that of the Mavi Marmara, the ship raided by Israel on its way to Gaza, but that of consistent economic and foreign policies aimed at achieving global relevance through regional leadership: sustained monetary and fiscal prudence, diversification of trade partners and energy sources, a feverish campaign to attract FDI and an effort to create an alternative area of increased economic integration with Turkey at its center.

These policies make up the more subtle indicators of Turkey’s transformation. Over the last eight years, Turkey has pursued economic policies that brought about robust growth, nearly tripling the gross domestic product. In the same period, the country’s trade volume more than quadrupled. While the share of the EU in Turkey’s exports decreased from around 60 percent to 45 percent, the share of the Middle East doubled, from 10 percent to 20 percent. More importantly, whereas in 2000, only eight countries made up 80 percent of Turkey’s exports, today that number is 16. The AKP government also made massive investments in infrastructure, increased the share of education in the fiscal budget and kept inflation under control.

At the same time, Turkey has pursued an ambitious policy of “zero problems” with her neighbors (with Armenia and Greece, as much as with Syria and Iraq). Despite the mixed success of these efforts effort, the intention to rid its borders of conflict highlights Turkey’s ambition of establishing the right conditions to grow as a regional power. The country also deepened ties with Russia, recently signing landmark cooperation agreements on issues ranging form energy to tourism. Prior to the fallout with Israel, Turkey worked hard to take on a mediator role to Israel’s conflict with Palestine and Syria. In Iraq, too, Turkey reached an understanding with the central government as well as the Kurdish regional authority.

It is only natural for a Turkey that is finally beginning to put her house in order is becoming more confident and demanding a bigger role in international politics. Ironically, this had been the kind of transformation that the EU had been waiting for to accept the viability of Turkey’s candidacy for membership. Now that the moment has arrived, the West should not get distracted and celebrate the arrival of a more powerful ally.

Alper Bahadir - A former management consultant at McKinsey & Company, Alper is currently pursing an MA in Public Administration in International Development at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government and an MBA at the Harvard Business School.