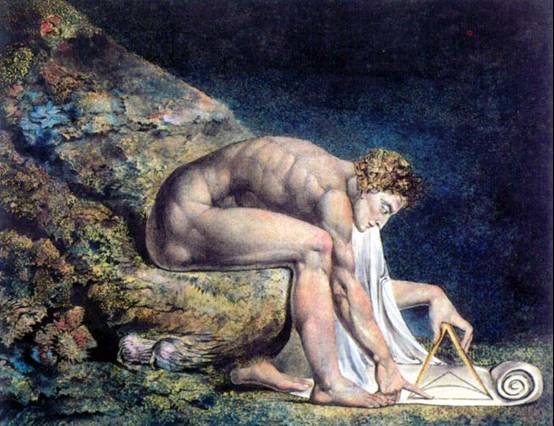

The impression was only reinforced by the sight as I came in of a massive reproduction of ‘The Ancient of Days’, the figure of a creator or demiurge crouching on the disk of the sun and leaning down with a pair of compasses. The actual image (hanging in the last room of this exhibition) is barely a foot in height, and yet here it was, as if projected on the museum wall, ready to dwarf any passing art critic below in the monumental way it deserved.

Sadly, Blake never managed to intimidate the critics of his own day. When already in his fifties, he exhibited in his brother’s house in Soho, above the Blake family’s haberdashery. The solitary review his work received was utterly, almost vindictively, dismissive, ridiculing him as an unfortunate lunatic who ought by rights to be in an asylum were it not for his mild manners. In other words, he was a harmless nutter. It was as damaging a review as the one that Shelley thought had killed Keats. Hardly anyone showed up, nothing sold and Blake, despite the adulation of far younger artists in his later years, never really got over it.

The disappointment must have been all the more intense as Blake had gone to great, maybe inordinate, lengths to big up his artistic reputation. He wrote a grand ‘catalogue’ to accompany the exhibition, fulminated against old masters he disliked, praised the good ones, indulged in a rambling critique of Chaucer, and so and so forth. As an experiment in self-promotion it was a disaster, but then a life of poverty and very little in the way of public profile lay behind it.

The exhibition at Tate Britain attempts to recreate that doomed display of 1809 by showing what has survived of the original show, though without the largest of the pictures, said by one punter to have been his masterpiece, as it has been lost. Blake wanted to encourage his audience to think of his pictures as frescoes, meant for a bigger scale than he had ever managed before, but he also wanted personal magnification of a kind, so that his fame could at last correspond to his undoubted talent. It’s painful to imagine him now, full of hope as he prepared for the big entrance onto Fame’s massive stage, self-consciously preparing the kind of works that might appeal to a contemporary British audience. What he came up with, among other pieces, were two grandiose failures, mythologised portraits of admiral Nelson and Pitt the prime minister which hover uneasily (and perhaps deliberately) between the sublime and the ridiculous.

The naked Nelson, his physique magically restored to full fitness by the visionary eye, wrestles into submission the forces of evil. The prime minister seems to be engaged in a similar enterprise, difficult yet made to look easy. There may be some Indian influence in the designs. There might also be a simplistic patriotism Blake hoped to inspire in his viewers. More obvious than any of this, however, is the strain to say something. For the whole of his artistic career Blake had been the prophet no one honoured in his own land – a true prophet of Albion, a bard like no other in England’s history – yet, at the very moment when he sought that honour most deliberately, tired of his stubborn obscurity and lack of money, he became inauthentic. The result doesn’t even seem like a ‘vision’ of the kind Blake is famous for, but a very calculated political overstatement. It’s a magniloquent dud, as unlike any of his celebrated works as it was possible for Blake to make it, and against the better judgement of a small-scale visionary who had recently urged us, in his ‘Auguries of Innocence’,

And a Heaven in a Wild Flower,

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an hour.

This question of the dimensions of William Blake’s work is addressed elsewhere in Tate Britain’s carefully curated show. At one point, we are shown the interior of a church with its altar graced by one of his religious pictures, blown way out of proportion. Other attempts to enlarge his works render the colours and shapes almost entirely abstract. This shadows the exhibition’s other main theme, the size of his reputation. The extent to which he was known in his lifetime (hardly at all, except by a very select group of patrons and friends) is explored through the people who knew and commissioned him, but it’s difficult to get very interested in these people, grateful as we may feel that they kept him going. A clerk who liked his work, a fellow poet who had turned down the laureate, his devoted wife Catherine who helped with the printing and colouring and who shared his enthusiasms – these are all worthy of gratitude, but they do little to help us understand the artist. Even the young men who called themselves ‘The Ancients’ – Samuel Palmer, notably, who referred to Blake’s house as that of ‘the interpreter’ and kissed the door knob whenever he passed – their idolatry of Blake may have made up in some small way for sixty years of neglect, but it contributes next to nothing to our comprehension of his work. It’s hard to imagine anyone who could, or any anecdote (there are plenty of anecdotes) that might shed light on his genius. Something in every human being is resistant to knowledge, even to self-knowledge. In the case of a man who saw angels at the age of six and was still conversing with them at sixty, who devised what he called an ‘infernal’ method of printing that reversed the normal processes, who was a Christian but utterly opposed to priests and organised religion, in short, a total one-off, the more one learns about him, the less explicable he becomes.

Blake has been co-opted on numerous occasions. E. P. Thompson, the great communist historian, thought he could trace his views to an obscure sect known as the Muggletonians; in other words, back to the radical puritans of the seventeenth century and a political tradition that rejected the church, kings and laws. They also didn’t like Newton.

Blake, famously, was not fond of Newton either, nor did he choose to worship in a congregation, but unlike the Muggletonians he did not even choose to sit with others and speak of the spirit. He was far too individual for that. There is a sense with him that he had fulfilled the logic of the dissenter tradition and reduced his life to a lonely pursuit of his own idiosyncrasy, hence the resolve to construct what Tom Paulin derides as ‘batty eccentricity’ and the bag lady’s trolley load of mythical heroes, emanations and spectres that took the place of his simpler, more succinct songs of innocence and experience. I think Paulin has a point. It is hard to like the epic poems, and hard not to regret this proud declaration from the last of them:

I will not Reason and Compare: my business is to Create.’

This independence of mind, admirable in itself, is possibly the most characteristic thing about Blake. Sadly, however, it didn’t only lead to what Paulin rightly calls the ‘tiny psychological myths’ of the Songs; it also led to an occult ‘system’ so complex that even W. B. Yeats struggled to comprehend it.

Again, the problem of Blake comes down to a matter of scale. The epic poems are too big, suffering from the same strenuous grandiosity as the picture of Nelson. In contrast, the best of his poems stick to his own advice about grains of sand. He was transcendently profound whenever he observed the small or the everyday and saw beyond it into a spiritual or psychological dimension. Then he could wander through London and perceive the hidden agony of those who populated the city:

Near where the charter’d Thames does flow

And mark in every face I meet

Marks of weakness, marks of woe.

In every cry of every Man,

In every Infants cry of fear,

In every voice: in every ban,

The mind-forg’d manacles I hear

Those manacles are real and metallic for the slaves in the West Indies, but psychological for those enslaved to the drudgery of capitalism. This is the same poet who lamented that ‘Pity would be no more / If we did not make somebody Poor / And Mercy no more could be / If all were as happy as we’ (‘The Human Abstract’). He’s a poet for our own unequal and often brutal times, painfully aware of what Robert Burns had called man’s inhumanity to man, a voice of moral outrage in the world’s most immoral city. That voice is less clear, however, when he refers to London as Golgonooza and subsumes it into his complicated ‘system’. Is there a problem of self-consciousness here? It may be sacrilege to those determined to see him as a prophetic figure, but the grandeur of that role had stylistic consequences. Prolixity was an obvious one, the tendency to epic poetic statements. He was also excessively conscious at times of other prophetic writers, such as Swedenborg, who he gave short shrift in the marvellous ‘Marriage of Heaven and Hell’, along with some over-cerebral angels:

‘I have always found that Angels have the vanity to speak of themselves as the only wise; this they do with a confident insolence sprouting from systematic reasoning. Thus Swedenborg boasts that what he writes is new; though it is only the contents or index of already published books’ (‘Marriage of Heaven and Hell’).

Angels are rational, almost bureaucratic in Blake. His devils have more imagination. But notice the phrase ‘I have always found’. This is cheeky and combative, implying that Blake is the real expert on angels, not his Swedish predecessor who speculated so exhaustively about them. The freeborn Englishman is defending his superior credentials as a seer.

Blake was more interesting when the spirit world took him by surprise and did the instructing. Similarly, he was most convincingly political when he was least conscious of being so, when he merely perceived the curses of the youthful harlot, or when he actually witnessed, with his inner eye, how

Runs in blood down Palace walls.

Just as politicians should not (as Tony Blair’s spin doctor once warned him) ‘do God’, so visionaries should not do politics. Explicitly, that is. Yet, for this very reason, people have striven to detect hidden political messages in Blake. Even when they encountered obscurity, it was easier than interpreting Jane Austen’s stubborn refusal to mention the war.

Nowhere has this obscurity been more tantalising than in Blake’s most famous poem, ‘The Tyger.’ It’s true, of course, that he was writing in the wake of the September Massacres in France and similar horrors of the French Revolution, but it is hard to reduce this or any of his other poems to a clear and simple political context. The language is utterly individual and concentrated, yet (unlike his epic poems) does not degenerate into idiolect. Instead, like so much of his best writing, it has an almost childlike simplicity:

In the forests of the night;

What immortal hand or eye,

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?

In what distant deeps or skies.

Burnt the fire of thine eyes?

On what wings dare he aspire?

What the hand, dare seize the fire?

And what shoulder, & what art,

Could twist the sinews of thy heart?

And when thy heart began to beat,

What dread hand? & what dread feet?

What the hammer? what the chain,

In what furnace was thy brain?

What the anvil? what dread grasp,

Dare its deadly terrors clasp!

When the stars threw down their spears

And water’d heaven with their tears:

Did he smile his work to see?

Did he who made the Lamb make thee?

Tyger burning bright,

In the forests of the night:

What immortal hand or eye,

Dare frame thy fearful symmetry?

Underneath the poem, Blake pictured a lugubrious looking tiger which has been compared to a cuddly toy. For a big cat, it seems rather small, and if it’s a cuddly toy, it resembles Eeyore more than Tigger.

This is a perfect instance of the unique power of an artist whose grasp of language was equalled by his skill in drawing. It seems incredible good fortune that a man who claimed to have regular visions of the dead and of eternity beyond ‘the world of generation’ should have been able to describe these things so beautifully, in word and image, yet we are often left none the wiser as to the meaning of his words or his pictures, as both remain obstinately impenetrable.

‘The Tyger’ is, on the face of it, simply a complement to another poem about a lamb, and always in Blake the lamb is Jesus, as well as being a very young sheep. The most obvious question the poet is asking is how such cruelty could be created by the same deity as created the lamb’s innocence, since this implies that he created both good and evil. For most readers, that would be sufficient food for thought.

But perhaps there is a more topical reference. The poem is full of rebels: it mentions Satan’s revolt (‘the stars threw down their spears’), Prometheus, a favourite rebel of the Romantics (‘What the hand dare seize the fire?’), and, perhaps Icarus (‘On what wings dare he aspire?’) – though this line might just as easily evoke Milton’s Satan. Peter Ackroyd suggests that the rebellion Blake may have in mind is a very real one:

‘Even as Blake worked upon the poem the revolutionaries in France were being branded in the image of a ravening beast – after the Paris massacres of September 1792, an English statesman declared, “One might as well think of establishing a republic of tigers in some forests in Africa”, and there were newspaper references to “the tribunal of tigers”. At a later date Marat’s eyes were said to resemble “those of the tyger cat’”.

Wordsworth, moreover, described post-revolutionary Paris as ‘a place of fear […] Defenceless as a wood where tigers roam’. All this sounds plausible enough if one assumes that Blake was aware of such commentaries, yet he had also written in ‘The Marriage of Heaven and Hell’ (1790-3) that ‘the tigers of wrath’ were ‘wiser than the horses of instruction’. The wisdom of tigers has something to do with their energy in a work that seeks to redeem evil from a bad press and to prove that the saintly Milton had himself, unwittingly, been of the devil’s party. In Blake, nothing is ever quite as simple as it first appears, but he definitely had a low opinion of priests:

‘As the catterpiller chooses the fairest leaves to lay her eggs on, so the priest lays his curse on the fairest joys’ (‘Marriage of Heaven and Hell’).

His spelling and dodgy entomology aside, the hostility here is unmistakable, but for Blake this was an example of gross understatement. Elsewhere, the priest becomes the male sexual organ, a literal embodiment of phallic power: ‘Embraces are Comminglings: from the Head even to the Feet,’ he insists, ‘And not a pompous High Priest entering by a Secret Place.’ One wonders if the ‘invisible worm’ that flew in the night and found out Rose’s bed (‘The Sick Rose’) had flown from a nearby seminary.

But ‘A Little Boy Lost’ gives us the cruellest account of priestly behaviour. It is as bad as anything in Goya. Here, a small boy states that love of oneself is natural and paramount:

And Father, how can I love you,

Or any of my brothers more?

I love you like the little bird

That picks up crumbs around the door.

It’s a form of cupboard love. The man of God is enraged by this. He forcibly removes the boy from his parents and burns him at the stake for suggesting that his own conception of love is more accurate than the priest’s holy Mystery. This cruelty is confirmed in ‘The Garden of Love’, where Blake’s righteous fury becomes almost unbearably poignant. It is as if priests have invented death itself in order to murder innocence. They don’t need to be explicitly infanticidal. They merely make it their business to blight childhood:

I went to the Garden of Love,

And saw what I never had seen:

A Chapel was built in the midst,

Where I used to play on the green.

And the gates of this Chapel were shut,

And ‘Thou shalt not’ writ over the door;

So I turn’d to the Garden of Love,

That so many sweet flowers bore.

And I saw it was filled with graves,

And tomb-stones where flowers should be:

And Priests in black gowns, were walking their rounds,

And binding with briars, my joys & desires.

Clearly, such men and their moral law were anathema to a dissenting individualist who always gave pews and pulpits a wide berth. Priests were the enemies of the Imagination, of Jesus (who Blake saw as Imagination incarnate) and, even when they invoked the concept, all that was ‘holy’. How to respond, then, to a revolution that sought to end their power across the Channel?

Though he would have cheered the aims of those who acted in the name of Liberty, it is hard to imagine Blake gloating over massacres. He was surely too much of a lamb for that. On the face of it, the poem about the ‘Tyger’ is primarily a meditation on the enigma of theodicy, the problem of how a good creator can permit the manifestation of evil.

But on this particular point, Blake was adamant throughout his adult life: God the Father was not good. He was Nobodaddy, the jealous patriarch who remains silent and invisible in the short poem of that name. This was the hostile demiurge with the compass in the picture, a figure he referred to as Urizen, which may have been a play on the words ‘Your reason’.

Urizen forges the very manacles of the mind which oppress humanity. He is the bringer of the Law, the laws of Moses and those of Newton alike. He is the calculating scientist and the highest of high priests. In ‘Vala, or The Four Zoas’ he actually crucifies Jesus. It was Urizen who created the tiger in all its stupid ferocity. If the most celebrated song of experience tells us anything about the poet’s response to violent revolution, it is that the tiger’s ‘wisdom’, and the Devil’s ‘heroism’, make for a very cruel politics. But on a more personal level, experience and priestly rule come at the same high price:

What is the price of Experience? do men buy it for a song

Or wisdom for a dance in the street? No, it is bought with the price

Of all that a man hath, his house his wife his children.

Wisdom is sold in the desolate market where none come to buy

And in the witherd field where the farmer plows for bread in vain.

(‘Vala, or The Four Zoas’)

The true dimensions of Blake are by turns infinite and minuscule. In a sense, he is beyond measurement, leaving the determination of quantity to the minds that know the price of everything and the value of nothing. He can be big and small, long-winded and terse, sometimes at the same time. There are lines of Blake which haunt you for a lifetime. Others just seem, for an ephemeral moment, as topical as any newspaper headline. Here for instance:

The selfish smiling fool and the

sullen frowning fool shall be both

thought wise that they may be a rod.

(‘Marriage of Heaven and Hell’)

The ‘selfish smiling fool’ is self-evidently Boris Johnson. The ‘frowning fool,’ it goes without saying, is his megalomaniac sidekick, Dominic Cummings. The rod in question, I would humbly submit, is the one that the British electorate have fashioned for their own back.

It has become a conventional observation that these are dark times in the English-speaking world. An atmosphere of unrest and division has prevailed on both sides of the Atlantic, and Britain has become polarised in a manner that William Blake would immediately recognise. We are in the throes of a full-blown political nightmare, as if the incubus from a painting by Fuseli (one of Blake’s friends) sits on the country, disturbing its sleep. The identity of this incubus is in some doubt. It looks like Cummings, but it’s acting exactly like Boris. Let’s call it Boris Cummings, then, or Dominic Johnson.

I can’t recall whether it had been one of my better nights lately, or whether the incubus had been back, but on the morning I attended the press preview of the exhibition, the media were abuzz with the idea of a ‘prorogation’ of parliament. That evening, as parliament was indeed suspended and its Conservative members quit the chamber, there were taunts of “Shame on you!” from the opposition benches. Then, once the governing party had left, the remaining MPs began to sing. One of the anthems they sang was ‘Jerusalem’, and the words of William Blake, set to music by Sir Hubert Parry, rang out across the House of Commons:

And did those feet in ancient time

Walk upon England’s mountains green…

The words are obscure, maybe – they are based on a legend that Jesus once visited England in the company of Joseph of Arimathea, a rich tin merchant – but they are incredibly well-known, to the extent that every line sounds like a cliché at first, though a cliché it would be hard to do without: ‘dark Satanic Mills’, ‘chariot of fire’ – it is an indication of the grip Blake has on the collective English imagination that these words are so familiar.

Sadly, familiarity has dissipated a lot of the energy in the original, but it is still possible to re-glimpse that energy if we take the words he used to introduce his ‘Songs of Experience’ literally:

Hear the voice of the Bard!

Who Present, Past, & Future sees

Whose ears have heard,

The Holy Word,

That walk’d among the ancient trees.

Here we have the Word, or Jesus, treading once again on the solid ground of England. It is a visitation of spiritual grace, and it is Blake who hears the holy footfalls.

Blake was part of a dissenting tradition in England that dated back to the seventeenth century and beyond. For the more radical dissenters, the coming of Christ’s kingdom was interpreted as the entry of Christ into every man and woman, a degree of literal godliness that put priests out of a job. In the exhibition, we can see an unusual painting of the Virgin and Child. It is rather stiffly interpreted and not what we have come to expect from endless Catholic versions of the subject.

As you gaze at the face of Jesus, you see how remarkably similar it is to a self-portrait by Blake elsewhere in the rooms. The eyes are far apart, the expression is knowing. It isn’t babyish at all.

Could this have been the accidental result of Blake’s lack of a model? I doubt it. The expression on the infant’s face is more like the unique blend of innocence and experience that characterises Blake’s vision. The infant embodies all the clear-sighted innocence of ‘the bard’.

As a child, Blake was spanked for claiming to have seen Ezekiel sitting under a tree. As a grown man, he would go one better and claim to be Ezekiel. He regularly saw visions. Angels he saw and depicted, along with the heads of dead men and women, even the ‘ghost of a flea’. He could readily see Jesus wandering through a wooded English landscape, because the bard/prophet could see past, present and future with equal clarity. And, in the words of ‘Jerusalem’ once reinvested with prophetic energy, Blake is obviously remembering the ascension of Elijah into the heavens on a chariot of fire, and simultaneously recalling the ascension of Christ into heaven from a hilltop, accompanied by Moses and Elijah. Christ’s face shines, just as his disciples once saw it shine:

Shine forth upon our clouded hills?

Blake himself becomes the new Elijah:

Bring me my Bow of burning gold

Bring me my Arrows of desire

Bring me my Spear: O clouds unfold:

Bring me my Chariot of fire!

Jesus is the burst of solar energy breaking through the English clouds. Whether the people who sang these words in the House of Commons knew it or not, they were expressing more than patriotic fervour; they were rehearsing a kind of English ecstasy.

And yet these words have not always been so familiar. As Tate Britain’s exhibition demonstrates, they were almost unheard till long after Blake’s death, and his stunning pictures known only to a select few admirers. Blake was a prophet par excellence, not honoured in his own lifetime, but rather ignored, or despised as crazy. I think his exhibition in Soho was misjudged, as if the elderly artist was tired of a life of obscurity and wanted to be accepted as a more conventional artist than he actually was. He probably had no inkling, old habits dying hard, that depicting Nelson as a flexing nude might strike critics as, well, stark raving mad.

The most ambitious picture in the exhibition, now lost, was called ‘The Ancient Britons’ and depicted the last battle of King Arthur. It was said to have been 14 feet (4.3 metres) wide by 10 feet (3 metres) tall, the largest picture Blake ever made, with what his catalogue described as ‘Figures full as large as Life.’ The young art student Seymour Kirkup said it was Blake’s ‘masterpiece’ and Henry Crabb Robinson called it “his greatest and most perfect work.” It’s sad that such a majestic piece could disappear, just like that. But then, what did size really matter to a man who could hold infinity in the palm of his hand?

‘William Blake’ is at Tate Britain until 2 February 2020.