The crusaders who left western Europe to “liberate” the Holy Land might seem to have little in common with contemporary Facebook users. But Libra, Facebook’s new cryptocurrency platform, tackles a problem that was familiar in the twelfth century. The spread of promissory notes (letters of credit) in the High Middle Ages caused an upheaval in Eurasian markets. Libra promises to do the same. And just as medieval financial innovations might require demystification, so, too, does Libra.

The crusaders had no easy way of bringing money with them. They couldn’t exactly wire funds or carry debit cards, and their coins were of little use in foreign lands. Gold was heavy and hard to move safely. The solution came from an unexpected source: the Knights Templar. The Templars were originally a Catholic military order that took up residence in Jerusalem, where they pledged to protect Christian pilgrims. They created the economic infrastructure for the Crusades, writing promissory notes in France or England that were redeemable in the Levant. A cipher based on the shape of the cross ostensibly guaranteed the notes’ security. In other words, the Templars created a variant on modern international transfer services, five hundred years before the first central bank.

Today, the demand mounts for a similar system, but on a global scale. Billions of people have no access to banks. Countless others endure high fees and slow transactions, especially when sending money across borders. What we consider a global financial system is, in reality, hardly global. Institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Bank of International Settlements, and the Financial Stability Board provide little more than a multilateral veneer over relationships that are primarily bilateral and dominated by commercial and central banks. Even within borders, moving money involves costly processes of settlement and exchange.

Facebook proposes a new kind of private multilateral institution: the Libra Association. It is based on blockchain technology, which first came to prominence with the cryptocurrency Bitcoin. A blockchain-type network creates a public ledger, a universally trustworthy account of who owes what. Just as the Templar cipher verified an otherwise forgeable piece of paper, cryptography will ensure that Libra cannot be spent twice or otherwise duplicated. Such technologically guaranteed, artificial scarcity allows cryptocurrencies to operate as money.

HOW IT WORKS

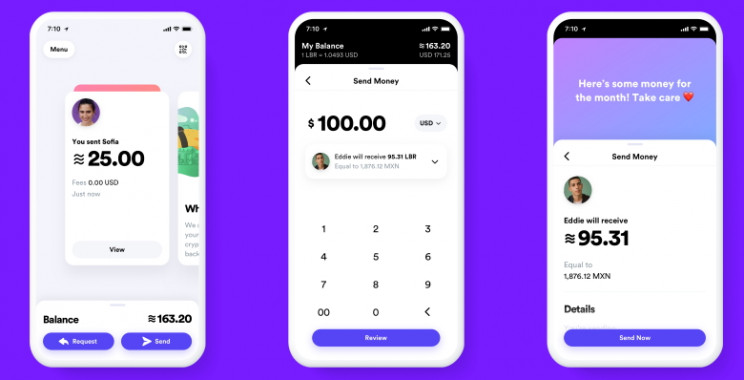

Libra will be redeemable at a fixed price for certain established currencies (such as dollars, euros, and yen). Members of the association will deposit assets in the Libra Reserve as backing any time someone wants to buy more Libra. As a result, whereas Bitcoin fluctuates wildly in value, Libra should remain relatively stable. That stability makes Libra potentially useful not only as a store of value but as a medium of exchange. Users will, Facebook argues, be able to send money around the world as easily as they send messages and videos.

Libra’s decentralized structure makes this new cryptocurrency both novel and potentially disruptive. The Libra Association had 28 members at the time of unveiling, including heavyweight firms from Visa to Vodafone. Facebook plans to grow this number to 100 by takeoff. None of the members can stop or reverse transactions—not even Facebook. Every member has a single vote on governance decisions. Bitcoin, by contrast, is even more decentralized. There is no association with any say over what network participants can do—there is only software, which anyone can run. But even though Libra is collectively governed, it is still more open than any established currency or digital payment system. The contents of the Libra transaction ledger will be public, the system will run on open-source software, and anyone will, in theory, be able to build wallets and other applications to operate on the Libra network.

Will Libra undermine financial institutions? Given Facebook’s scale and track record, the possibility deserves to be taken seriously. In addition to banking the unbanked, Libra could replace traditional intermediaries in cross-border transactions, such as remittances, which amount to more than $600 billion per year. Libra could also end up reducing the power of central banks in countries with weak currencies or strong capital controls, because it will allow people to move their money out of these countries more easily. If enough funds are pledged to the Libra Reserve, Libra could become a gigantic shadow bank distinct from, yet connected to, the existing financial system.

The situation bodes ill for governments tasked with regulating and monitoring transfers of wealth. For one, Libra could hinder efforts to counter money laundering and terrorist financing. Additionally, states will need to apply securities, banking, and other classes of financial regulation to the Libra Association and the Libra currency. How they will do this remains unclear. Finally, Libra will have to answer to public and private actors—panicked about financial instability—should users pull money out during a crisis.

These issues will take time to work through, even if Libra successfully runs the gauntlet. At a minimum, Facebook’s mid-2020 start date seems wildly optimistic. Ten years ago, regulators might have waited to see what problems emerged over time. Today, they will be significantly more aggressive at the initial stages. Facebook is already in the crosshairs of governments around the world, and the stakes are nothing less than the stability of the global economy.

Ultimately, Facebook’s initiative will accelerate the efforts now under way to fit cryptocurrencies and blockchain-based applications into legal and regulatory frameworks. By regulating new technologies, governments impose costs and limitations on innovative tools like blockchain. In the long run, however, such boundaries are healthy. Blockchain-based systems must themselves be trustworthy to serve as platforms for exchange. Much of the current financial system is antiquated below the surface. Blockchain is a more efficient technology, but the aura of illegality and fraud is a major impediment to its adoption.

LIBRA AND ITS NEMESES

The country with the most to lose from Libra also has the most to gain from a revolution in the global financial system. That country is China. China bans Facebook and forbids trading in cryptocurrencies (such as Bitcoin) that could circumvent its capital controls. China is also home to the world’s biggest digital payments systems. WeChatPay and AliPay together process as many transactions in a day as the United States does in nine months. They operate only with China’s own currency, the renminbi, and they are centrally controlled, which makes payments easy for the government to access or limit. Facebook’s argument to regulators is that if an American company doesn’t move aggressively into blockchain-based payments, China will. The truth is that Facebook’s entry has accelerated China’s movement in this direction.

No country is more interested than China in displacing American hegemony over global financial institutions. Cryptocurrency serves that objective. To that end, Beijing established a Digital Currency Research Lab two years ago and is exploring its own alternative to Libra. Perhaps the next move will be for the G-7 countries, who want neither a Chinese-dominated system nor a Facebook-dominated one, to establish their own global digital currency instrument. There is also the IMF, whose director, Christine Lagarde, has already hinted at a possible “IMFcoin” based on the IMF-sponsored assets known as Special Drawing Rights.

In the end, new financial institutions will likely supplement the existing ones rather than replace them. New systems have to interface with old ones. And there will always be tradeoffs. If you want to make it frictionless for anyone to send money around the world without cumbersome identity verification, you cannot simultaneously make it hard for someone subject to U.S. sanctions to pay terrorist organizations or money launderers. Libra might develop better mousetraps, but at the cost of accessibility and ease of use. Facebook will have to find a balance that works.

Should the company be tempted to push too hard with Libra, the history of the Templars may be instructive. Money transfer helped the order become one of the wealthiest institutions in medieval Europe—a sprawling financial empire and powerful creditor to kings. After the crusaders were pushed out of the Levant, however, the Templars languished. And then the order collapsed abruptly at the beginning of the fourteenth century. The French King Philip IV, deeply in debt to the Templars, arrested and tortured many of its members on trumped-up charges of heresy. He eventually convinced the pope to ban the order, coincidentally canceling his debts. The Templars’ power and wealth were their undoing. Facebook should take heed.

This article was originally published on ForeignAffairs.com.