A LETTER FROM AN OLD ACQUAINTANCE

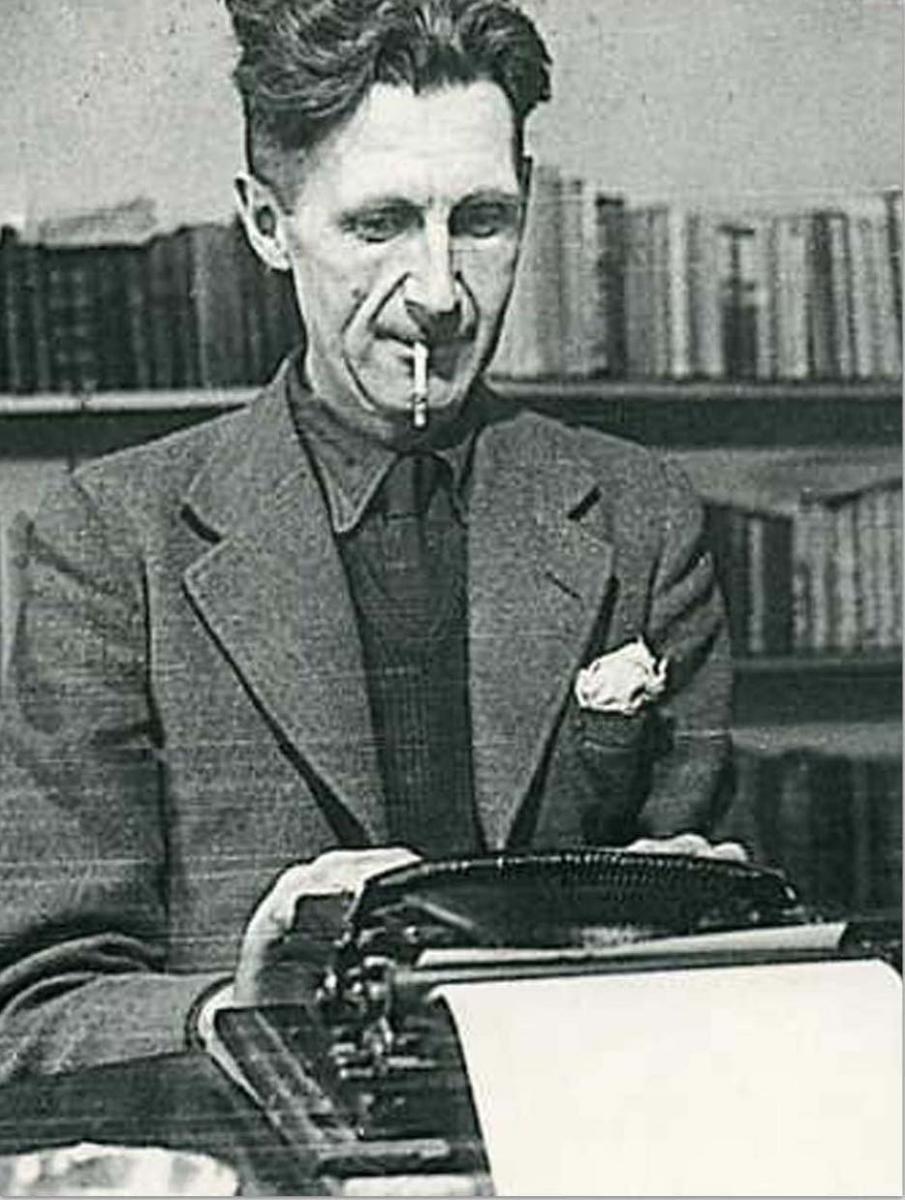

Late autumn in 1949. A letter arrives on George Orwell’s doormat all the way from California. He might also feel it has come from a long time ago: the writer was one of Orwell’s tutors while he was at Eton College, the famous public school in England that is currently supplying us with prime ministers of an ever-declining standard.

Orwell remembers Eton very well. He has even written about it. Unlike its more contemporary products, he emerged from Eton’s ancient walls with a very unconventional, downright left-wing view of the world. The same might be said, guardedly, about his ex-tutor. At the very least, the older man has an open mind. Still, there is something didactic in the tone of his letter. It is by turns congratulatory and critical, like an end of term report:

Dear Mr. Orwell,

This must have felt rather an odd way to be addressing the former pupil. Orwell would have appeared as ‘Eric Blair’ in his tutor’s class register.

It was very kind of you to tell your publishers to send me a copy of your book. It arrived as I was in the midst of a piece of work that required much reading and consulting of references; and since poor sight makes it necessary for me to ration my reading, I had to wait a long time before being able to embark on Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Ah yes, poor eyesight; Orwell would have remembered this about his tutor. When the older man had himself been a pupil at Eton, he’d contracted an eye disease which left him ‘practically blind for two to three years.’ The symptoms would have included constant pain, impaired eyesight and photophobia or light sensitivity. Half-blind in one eye, he would later be rejected by the British Army when he volunteered in 1916. Later still, his brother wrote:

I believe his blindness was a blessing in disguise. For one thing, it put paid to his idea of taking up medicine as a career ... His uniqueness lay in his universalism. He was able to take all knowledge for his province.

Maybe it also had something to do with his prophetic powers. Tiresias had been blind. By the time Milton went blind, he was no longer honored in his own country.

The writer of the letter, having praised the book he has been sent, moves swiftly onto the substance of the novel:

May I speak of the thing with which the book deals — the ultimate revolution?

Orwell might have been slightly mystified; the concept of the ‘ultimate revolution’ was by no means explicit in his book. Nonetheless, the letter was insistent:

The first hints of a philosophy of the ultimate revolution — the revolution which lies beyond politics and economics, and which aims at total subversion of the individual's psychology and physiology — are to be found in the Marquis de Sade, who regarded himself as the continuator, the consummator, of Robespierre and Babeuf.

This is the mad Marquis in his role as political philosopher; not, perhaps, the role which is most familiar to us now…

As a previous Etonian prime minister might have put it, nowadays we tend to associate de Sade with ‘maso-sadism’. He is just half of a comedy duo, forever playing straight man to Sacher-Masoch’s dumb ass. They’re like the Morecombe and Wise of sexual perversion: Bring me sunshine with your rictus of pain. But in a dystopia, sadomasochism is no longer for the purposes of harmless entertainment:

The philosophy of the ruling minority in Nineteen Eighty-Four is a sadism which has been carried to its logical conclusion by going beyond sex and denying it. Whether in actual fact the policy of the boot-on-the-face can go on indefinitely seems doubtful. My own belief is that the ruling oligarchy will find less arduous and wasteful ways of governing and of satisfying its lust for power, and these ways will resemble those which I described...

It’s an odd kind of letter to be sending. Did Orwell sense the strangeness of the situation? Here was the greatest of his prophetic competitors writing to question his own vision of the future. If there had never been any anxiety of influence on Orwell’s part before this moment, he must have been experiencing high anxiety by now. Perhaps he resented the tutorial. He surely would have been uncomfortable with the idea of being indebted to de Sade. The boot stamping on a human face – forever – had more to do with the totalitarian systems he had encountered than anything he could have learnt from a degenerate French aristo.

The point, however, is that the letter writer disagreed about the practicality of revolutionary cruelty. In the same pedagogical tone, he proceeded to put his old pupil right about hypnotism, possibly with reference to the famous scene where Winston Smith is coerced into believing that two and two make five, though the letter writer makes no specific mention of this:

Partly because of the prevailing materialism and partly because of prevailing respectability, nineteenth-century philosophers and men of science were not willing to investigate the odder facts of psychology for practical men, such as politicians, soldiers and policemen, to apply in the field of government. Thanks to the voluntary ignorance of our fathers, the advent of the ultimate revolution was delayed for five or six generations. Another lucky accident was Freud's inability to hypnotize successfully and his consequent disparagement of hypnotism. This delayed the general application of hypnotism to psychiatry for at least forty years. But now psycho-analysis is being combined with hypnosis; and hypnosis has been made easy and indefinitely extensible through the use of barbiturates, which induce a hypnoid and suggestible state in even the most recalcitrant subjects.

This sounds like ‘hypnopedia’ and the use of a happy drug, soma (always italicized), to control people’s natural urge to rebel. The recipient of the letter might have been wondering by this time what any of this had to do with his own book. He would soon be enlightened:

Within the next generation I believe that the world's rulers will discover that infant conditioning and narco-hypnosis are more efficient, as instruments of government, than clubs and prisons, and that the lust for power can be just as completely satisfied by suggesting people into loving their servitude as by flogging and kicking them into obedience. In other words, I feel that the nightmare of Nineteen Eighty-Four is destined to modulate into the nightmare of a world having more resemblance to that which I imagined in Brave New World. The change will be brought about as a result of a felt need for increased efficiency.

The writer of the letter was no less a literary star than Aldous Huxley. Here, as one Etonian to another – and, more to the point, one visionary to another visionary – he was saying: ‘This is all fine, up to a point. But it’s far too crude, old chap. You may have seen one possible future, but it’s not a sustainable one. My vision is better than yours for a simple reason – it’s further off. I may not be able to see enough to read these days, but I can foresee things better than you ever could.’

Search as I might, I have been unable to track down Orwell’s reply to Huxley. Perhaps he was not minded to get back to him. Could it be he was too dignified to rise to the challenge? After all, as far as Huxley was concerned, the younger man’s short-sighted nightmare was destined to modulate into his own, a far more far-sighted nightmare. They could both be right, but one would turn out more right than the other.

Ultimately, it would take an optician of the distant future to decide the issue. For the purposes of these articles, and with no training or phoropter at my disposal, I shall endeavor to be that optician.

FORD, THE ANCESTRAL INFLUENCER

On those same televisions, a light-hearted show appears, named after his infamous Room 101, the place where people encounter their worst nightmare. In his hero’s case, that is a face-chewing rat. The modern version of the show merely allows guest celebrities to dispose of annoying aspects of modern life, after first convincing the host of the program that said annoyances deserve to be ‘banished.’ Here is a sample of the kinds of things that have been successfully reviled:

Acceptance speeches at award ceremonies

People who misuse the word ‘literally’

People who recline seats on airplanes

Food that doesn’t taste as good as you remember

Predictive text

Cyclists in Lycra

German pop music

Actors

Which brings us full-circle to acceptance speeches at award ceremonies. Nothing controversial here, you might say. Strangely, no one has ever mentioned deliberately starved rats on the program. Perhaps Orwell has the copyright on that particular annoyance.

These annoying aspects are then binned. It’s all a bit tame, admittedly, but nevertheless, it’s interesting that Orwell has such prominence on the television, almost as if the medium has a guilty conscience. Beyond trivia like this, however, the way that Orwell shows up in modern life is more subtle. In other words, he hardly shows up at all.

Nor, frankly, does Huxley in the obvious, quotidian reality we are living through, but given that his dystopia was more of a satire than a nightmare, it was a satire on what he observed in the America of the Thirties, which was symbolized by the advances of Ford’s mass production. It is essentially a capitalist dystopia, producing endless items for consumption. Ford has replaced the deity and, instead of being in his heaven, he is in his Flivver (the little plane he designed), an immortal forefather figure buzzing overhead and invoked whenever characters refer to God, as in “Thank Ford for that!”

What Orwell dreaded, in contrast, was a kind of totalitarian Bolshevism where techniques of mind control were practiced by a police state on steroids. As we saw in Part One, the cops in the brave new world have no need of truncheons or rubber bullets, let alone gulags. All they need do is douse the flames of insurrection with soma. They spray it about the place as soon as trouble arises, in a manner reminiscent of the foam in an Ibiza night club.

The way to keep people docile and compliant is not to beat them up, but to butter them up. Give them plenty of what they want. And make sure they want what you want them to want. Make them consume your stuff.

This was Huxley’s genius – he projected American consumer culture into the distant future, creating a Prozac nation where the will to rebel or to express one’s individuality has been schmoozed out of the populace by a process of suggestion and perpetual love-bombing. How could anyone rise up against such a state? How could anyone seriously object to being this happy? Life in this future would be one massive orgy. Everyone would be productive. There would be no unproductive nature worship, for example. The music would be synthetic. People would do sports that encouraged consumption of the equipment to do them. Games like the ludicrously named Centrifugal Bumble-puppy, the rules of which Huxley never bothers to explain. People would be reared to like their inescapable social destiny. It’s their duty to be infantile because ‘Our Ford loved infants.’ The passage describing a Solidarity Service in Chapter Five, which Bernard Marx attends with some reluctance, is pure Ibiza.

But before that, Bernard heads for the center of London with Lenina, to the newly-opened Westminster Abbey Cabaret. Electric sky-signs announce LONDON’S FINEST SCENT AND COLOUR ORGAN. ALL THE LATEST SYNTHETIC MUSIC. Sixteen ‘sexophonists’ (sic) play as they enter a hall scented with ambergris and sandalwood. Huxley, who was an occasional music critic, has great fun with the suggestive innuendo in his description:

The sexophones wailed like melodious cats under the moon, moaned in the alto and tenor registers as though the little-death were upon them. Rich with a wealth of harmonics, their tremulous chorus mounted towards a climax, louder and ever louder – until at last, with a wave of his hand, the conductor let loose the final shattering note of ether-music…

(ether-music is one of those uncanny moments of prescience)

…and blew the sixteen merely human blowers clean out of existence. Thunder in A flat major. And then, in all but silence, in all but darkness, there followed a gradual deturgescence, a diminuendo sliding gradually, through quarter tones, down, down to a faintly whispered dominant chord that lingered on (while the five-four rhythms still pulsed below) charging the darkened seconds with an intense expectancy. And at last expectancy was fulfilled. There was a sudden explosive sunrise, and simultaneously, the Sixteen burst into song:

Bottle of mine, it’s you I’ve always wanted!

Bottle of mine, why was I ever decanted (i.e. born)?

Skies are blue inside of you,

The weather’s always fine;

For

There ain’t no Bottle in all the world

Like that dear little Bottle of mine.

I shall return to the question of synthetic music below. For the moment, I should explain that the ‘bottle’ in the song is the one all inhabitants of the brave new world are blissfully trapped inside. It’s probably the same bottle as described by Mustapha Mond, Resident World Controller of Western Europe, in Chapter 16 as ‘an invisible bottle of infantile and embryonic fixations.’ It’s the bottle of soma-holiday. It’s what would happen if you could take happiness and, well, bottle it. As the sexophones fall silent, their ecstatic tones are replaced by ‘the very latest in slow Malthusian Blues’ and the couple ‘might have been twin embryos gently rocking together on the waves of a bottled ocean of blood surrogate.’ To understand this image, one has to refer back to Chapter One and the process by which humans are created in this ‘brave future where you can forget your past’ (Bob Marley sang ‘bright future’ and ‘you can’t forget your past’, but then he may not have been thinking dystopian thoughts when he wrote that song). The message in Huxley’s bottle is clear: a promise of no messages and no thoughts, just a gentle oceanic feeling of harmony summed up in the words Community, Identity, Stability.

This harmony is not always as complete as it seems. When Herbert goes alone to a Solidarity Service we see how, even in the midst of Ibiza, a malcontent wallflower can lurk unseen, simply by dancing.

Bernard arrives at the sky-scraping ‘Singery’ as it is called on Ludgate Hill. Having made his way in a lift to the appointed room, he enters. Thank Ford, he is not the last! In his rush, however, he sits next to the wrong woman. Her name is Morgana Rothschild:

Morgana! Ford! Those black eyebrows of hers – that eyebrow, rather – for they met above the nose. Ford! And on his right was Clara Deterding. True, Clara’s eyebrows didn’t meet. But she was really too pneumatic.’

One instantly feels for Bernard in this age of the on fleek eyebrow and the enhanced bosom. These are details, but as usual, the book effortlessly anticipates the conditions which prevail almost a century after it was written. The terror of eyebrows is an authentic prophecy, but why is Bernard so terrified? The answer is that when the President of this gathering has made the sign of the T (no crucifixes here) and switched on the synthetic music, a spiritual orgy is due to begin. He will be expected to become intimate with whomsoever is closest to hand, one eyebrow or two. This act of union is heralded by the First Solidarity Hymn. ‘Dedicated soma tablets’ are placed in the center of the table around which the twelve celebrants sit and more soma is passed around. They drink to their annihilation, as you do, and then sing:

For we are twelve, oh, make us one,

Like drops within the Social River;

Oh, make us now together run

As swiftly as thy shining Flivver.

Bernard starts to feel the love, but still Morgana’s monobrow holds him back. The soma cup returns and this time they drink to ‘the imminence of His Coming’, but the eyebrow ‘continued to haunt him’ – he is unable to believe in the imminent coming. He expects failure and smiles broadly regardless. By this time they are openly welcoming the death of their separate egos and the music is replaced by a Voice somewhere above their heads saying very slowly “Oh Ford, Ford, Ford.” A sensation of warmth ‘radiated thrillingly out from the solar plexus to every extremity of the bodies of those who listened; tears came to their eyes; their hearts, their bowels seemed to move within them.’

This is surely intended as a comic swipe at his friend D. H. Lawrence’s fixation with the solar plexus, quasi-mystical center of the human frame. The movement of the bowels seems to portend a more obvious and scatological outcome. Thankfully, no such accident occurs. Instead, the footsteps of the Greater Being are now heard by the celebrants.

There is a heavy hint of Blakean mysticism in all this and the words of what many consider the alternative national anthem, ‘And did those feet in ancient time’ or Jerusalem. Even George V preferred it to the rather dreary God Save the King. Blake’s poem draws on the description of the Second Coming in Revelations and what must have seemed a far-fetched account of the Messiah visiting Glastonbury, though this would finally come to pass in 2017.

Suddenly, Morgana springs to her feet. “I hear him, I hear him,” she cries. Others follow with the same affirmation until Bernard feels compelled to stand up too. Though he hears nothing, he replicates the enthusiasm of the others, even shuffling and jigging up and down like them. Everyone then goes round in circular procession, ‘stamping to the rhythm of the music, beating it out with hands on the buttocks in front; twelve pairs of hands beating as one; as one, twelve buttocks slabbily resounding.’

I think it’s fair to say that Huxley was somewhat ahead of our time here, let alone his own, unless I have been sadly misinformed about the newest dance crazes sweeping the clubs.

The climax of all this shuffling and bottom slapping comes with the boom of a great synthetic bass as the Twelve-in-One arrives, the incarnation of the Greater Being, and sings over feverish tom-toms:

Orgy-porgy, Ford and fun,

Kiss the girls and make them One.

Boys at one with girls at peace;

Orgy-porgy gives release.

What a song for our #MeToo times, bedevilled as they are by atrocious relations between the sexes and a fear of intimacy, though who, in this inhibited era, would dare sing it? The innocence of the original playground song – “Georgy Porgy pudding and pie / Kissed the girls and made them cry” – gives the whole scene an air of juvenile gaiety, utterly appropriate to the future Huxley has seen. No woman will have to cry in this dystopia, unless it’s with joy. The identity of Georgy will be obliterated in Orgy and with the disappearance of the ego they ‘wavered, broke, fell in partial disintegration on the ring of couches which surrounded – circle enclosing circle – the table and its planetary chairs.’ Everything turns red as if they are back in the womb. In the red twilight ‘it was as though some enormous negro dove were hovering benevolently over the now prone or supine dancers.’

I suppose the less said about that dove the better; even prophetic writers must sometimes betray the prejudices of their own lifetime. It is not clear what, if anything, the supine dancers get up to on the couches. A discreet veil is quickly drawn, some would say not quickly enough.

On the roof of the building afterwards, to the sound of Big Henry (the renamed Big Ben), Bernard and one of the women compare notes. She is in the appropriate raptures, though in a satiated, calm way; to be excited would show a lack of satisfaction. “Didn’t you think it was wonderful?” she asks him. “Yes, I thought it was wonderful,” he lies. It is a moment of profound loneliness and failure:

Separate and unatoned, while the others were being fused into the Greater Being; alone even in Morgana’s embrace…

Clearly, he has persevered in the attempt to overcome his repulsion.

…much more alone, indeed, more hopelessly himself than he had ever been in his life before. He had emerged from that crimson twilight into the common electric glare with a self-consciousness intensified to the pitch of agony. He was utterly miserable, and perhaps […] it was his own fault. ‘Quite wonderful,’ he repeated; but the only thing he could think of was Morgana’s eyebrow.

Is it any wonder, given his antagonistic attitude and his dark moods, that Lenina finds Bernard odd? He is a lone malcontent in the midst of unanimous ecstasy, the kind of queer fish who, in the unlikely event of fetching up in an Ibiza night club, would slope off to bed early complaining of a headache, then be up before everyone else the next day, combing the island for authenticity. His friends would eventually track him down in a remote cave somewhere, attempting to read Don Quixote in the original Spanish. Fanny (Lenina’s best mate) offers the only plausible explanation: too much alcohol in his blood-surrogate.

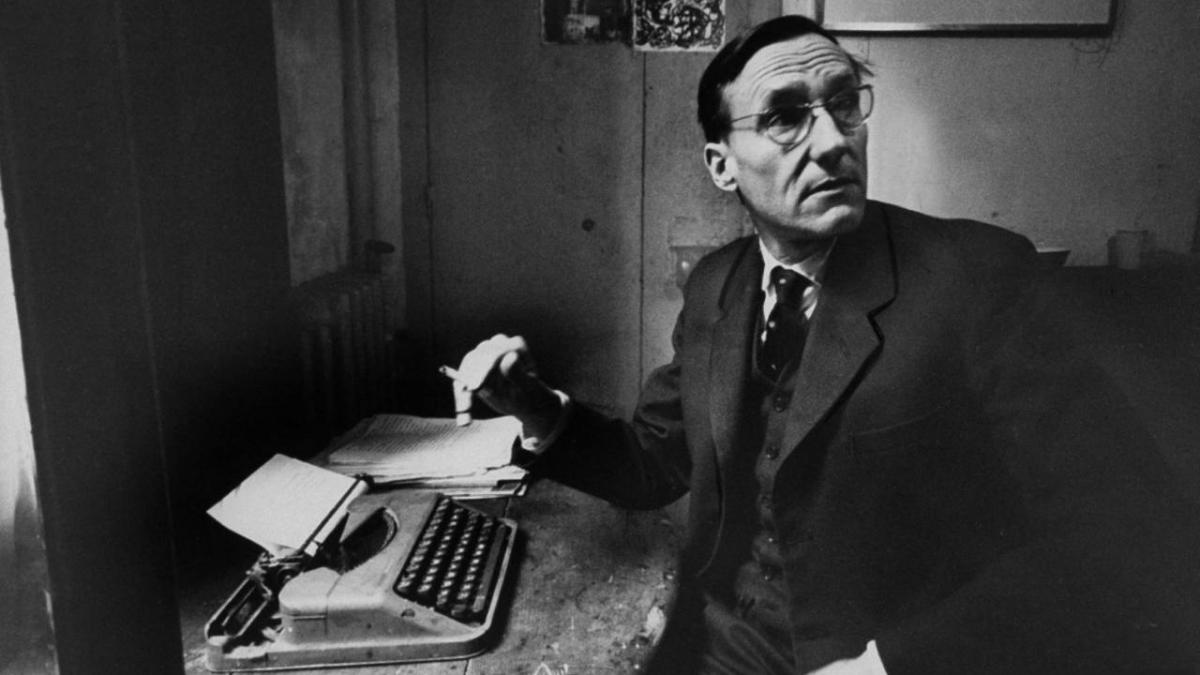

THE UNINSPIRED WRITER

‘Interzone trippin’ and I’m off to Annexia.

I gotta get a typewriter that’s sexier.’

From ‘Bug Powder Dust’ by Bomb the Bass, featuring Justin Warfield

There is no song in this world denser in its references than ‘Bug Powder Dust’. It is beyond doubt a rap lyric, but it’s also a literary tour of Sixties hip mythology and a tribute to the work of William S. Burroughs, which is why I always assumed the line about getting ‘a typewriter that’s sexier’ came from Naked Lunch, just like the bug powder itself, the Interzone and the dystopian Annexia. But it turns out these were massive assumptions. I am not in the mood to reread Naked Lunch for the first time in over forty years, so I may never learn if the words are indeed from there. The author’s grandfather made adding machines; Burroughs typewriters were made by a separate branch of the family. Did Burroughs express the desire for a typewriter with more pneumatic qualities? I guess certain things are supposed to remain a mystery, and it’s probably better that way.

When George Orwell received that letter from his old teacher, he might have experienced a twinge of regret that his own typewriter was not sexier. The older writer was certainly wittier than the younger one. He was so suave, and his dystopia was such good fun, one struggled to think of it as dystopian at all. Nothing quite like Orgy-Porgy appears in Orwell’s work. From a spirit of hedonistic experiment that Huxley might well have picked up during the Twenties, we move instead into an Orwellian world of grim austerity. There is a love affair at the center of the narrative, but as we shall see it carries little of the sexual charge that animates the older book. Harmless fun it is not.

Actually, the idea is ridiculous. Orwell would not have had any reason to feel a twinge, knowing as he did that his enterprise was entirely different. While Huxley was an experimenter and a little bit of a thrill-seeker, it is hard to see Orwell’s spell as a defender of the Spanish Republic or as a ‘down and out’ as bouts of hedonism. His muse was far more somber than Huxley’s, as was his prose. While both the old Etonians drifted as far away as possible from the playing fields and cloisters they had known, their paths could hardly have been more different.

Still, in his wittier, more satirical book, Huxley gives us one figure who suggests the problem of happiness for a writer. While Orwell could dwell on the misery of his dystopian vision and frighten us with its horrors, Huxley had to work harder at giving us some kind of handle on the soma pleasures of his future, just because happiness is not so interesting.

Helmholtz Watson is the writer in this happy society. A close friend of Bernard, he is an Alpha-Plus, which in the categories of the novel defines him as intelligent and a man of some stature. Women find him irresistibly attractive. He lectures at the College of Emotional Engineering and, in the intervals between lectures, is a ‘working Engineer.’ He writes regularly for The Hourly Radio and has ‘the happiest knack for slogans and hypnopaedic rhymes.’ Helmholtz is very able, maybe too able; he suffers from an excess of thinking, a feeling of apartness like his less successful friend, which leads to disenchantment with the pleasures of the flesh and disappointment with his own jingles. He intimates his concerns to Bernard in a disarming way, as if he has only the faintest intimations of the problem himself:

I’m thinking of a queer feeling I sometimes get, a feeling that I’ve got something important to say and the power to say it – only I don’t know what it is, and I can’t make any use of the power. If there was some different way of writing… Or else something else to write about […] I’m pretty good at inventing phrases – you know, the sort of words that suddenly make you jump, almost as though you’d sat on a pin, they seem so new and exciting even though they’re about something hypnopaedically obvious. But that doesn’t seem enough’ (Chapter Four).

Helmholtz is similar to Orwell’s Winston Smith in his line of work, which amounts to dumbing down the English language. Yet, in Helmholtz there remains an obscure conviction that he is better than this. Eventually, he gets himself into trouble for handing out one of his own poems to his students – on being alone. Solitude is definitely not the kind of topic any brave new writer should be attempting. Nor has he had sufficient practice to pull it off, so the result is strangely flat and prosaic, despite its erratic rhymes, and he is still unable to transcend the level of erotic routine:

Absence, say, of Susan’s,

Absence of Egeria’s

Arms and respective bosoms,

Lips and, ah, posteriors,

Slowly form a presence;

Whose? And I ask, of what

So absurd an essence,

That something, which is not,

Nevertheless should populate

Empty night more solidly

Than that with which we copulate,

Why should it seem so squalidly?

The inarticulacy is painful. It is the garbled sound of emotional unintelligence even as it struggles to feel. It is bad art and bad feeling. Yet, there is a kind of pathos here, owing to the way he gropes for something less squalid, which we might call love.

Bernard is not surprised by the scandalized reaction of the students and the Principal. After all, they have (in their sleep) received ‘at least a quarter of a million warnings against solitude.’

The result of all this inarticulacy is that Helmholtz only senses that he is a writer. When the Savage recites the story of Romeo and Juliet to him, he fails to grasp the tragedy of the situation, so amused is he by the incongruous idea that Juliet has a mother, for instance, or that people get buried in tombs rather than having their phosphorous recycled. Helmholtz laughs at the idea of ‘getting into a state about having a girl.’ The entire emotional structure is incomprehensible. ‘And yet,’ he tells the Savage,

‘I know quite well that one needs ridiculous, mad situations like that; one can’t write really well about anything else. Why was that old fellow [i.e. Shakespeare] such a marvelous propaganda technician? Because he had so many insane, excruciating things to get excited about. You’ve got to be hurt and upset; otherwise you can’t think of the really good, penetrating, X-rayish phrases. But fathers and mothers!’ He shook his head. ‘You can’t expect me to keep a straight face about fathers and mothers. And who’s going to get excited about a boy having a girl or not having her? […] No,’ he concluded, with a sigh, ‘it won’t do. We need some other kind of madness and violence. But what? What? Where can one find it […] I don’t know,’ he said at last, ‘I don’t know’ (Chapter Twelve).

It is Helmholtz’s fate to fall foul of the rules and be banished to an island, but this actually excites him. The Controller offers him the chance of living in a tropical paradise. Helmholtz opts for the rigors of the Falklands. ‘I believe,’ he says, ‘one would write better if the climate were bad. If there were a lot of wind and storms, for example…’ It’s hard to imagine that he will ever be a good writer, even among the icy winds and the penguins, but Helmholtz is at least aware enough to know what he lacks. Friction, essentially.

Likewise, Orwell was to head for a cold, windy island to write his great dystopia. Far from the metropolis, it was called Jura and situated in the remote Scottish Hebrides.

This was hardly a surprising choice. Orwell had always been familiar with the stimulating qualities of adversity. There would be little in the way of hedonistic pleasures to relieve the bleakness of his future.

A FOOTNOTE ON SYNTHETIC MUSIC

The nature of the soundtrack to the lives of people in Huxley’s dystopia is difficult to imagine. Quite possibly it is a species of jazz, hence the color of the eucharistic dove at the climax of the orgy. It might equally well resemble muzak of the kind played in lifts and airport lounges. Ease of listening would definitely be a necessary attribute.

But, just possibly, it is neither of these things. It is simply modern pop since music ain’t what it used to be either. Thoughty2 has a YouTube video entitled The TRUTH Why Modern Music Is Awful. It’s over twenty minutes long, and yet anyone who has managed to read this far cannot be suffering from too short an attention span and I recommend they watch it.

In essence, and according to the Spanish National Research Council (2012), the argument goes that modern music has been impoverished along three metrics: harmonic complexity, timbral diversity, and loudness. The often bewildering number of instruments in the old pop songs (notably in the Beatles’ ‘A Day in the Life’) has been reduced down to keyboard, drum machine, sampler and computer software, which tends to ‘suck the creativity out of music.’ Melodies, rhythms and even vocals are increasingly similar. The ‘millennial whoop’ has become omnipresent, though it’s difficult to reproduce here.

As for marketing, the enforced familiarity of tunes is used to get past people’s shorter attention spans and assure them that everything is fine – a very Huxlean concept.

Lyrics have measurably declined in complexity. A vast amount of material is written by Max Martin and Lukasz Gottwald, whoever they are.

The hook, which gets people interested in a song, occurs sooner and happens more often.

Through ‘dynamic range compression,’ the loudness of the song is more uniform, at the cost of muddying the sound and breaking down its nuances.

And, because of the huge expense of promoting music nowadays, the industry has rejected the model of trying new bands or acts out on the public, instead of telling the public what it should like and limiting the risk. Through a process of relentlessly plugging a tune, the ‘mere-exposure effect’ kicks in. After initial indifference to, or even repulsion from, a tune, the release of dopamine that occurs when something familiar is heard takes over, and before long you like it enough to keep playing it, repeatedly.

Thus, ‘music as an art form is dying.’ Or, to put it another way, it is becoming ether-music.