For some time now, I’ve been preoccupied with eyebrows in a way few men have ever been. Not since the obsessive young man described in Shakespeare’s pastoral comedy, As You Like It, has anyone been more obsessed than me. It’s not the case that I want to pen woeful ballads on the subject; I’m simply obsessed with finding out what has happened to the eyebrows I once knew.

As is so often the way with obsessions, I can date the birth of this one with precision. It happened during a period of freak weather we had in February. It was an unseasonably warm afternoon and I was in a brightly sunlit room, ordering lunch. As I did so, I glanced at the waitress. She was young, smartly dressed and her manners were impeccable. She took my order with an amiable smile. But the sad fact is, I would certainly recall nothing about her now, were it not for her eyebrows.They had something about them that disturbed me, these eyebrows. They were not of a kind I had ever set eyes on before. I had the strange sensation they were not even hers. Of course, they were hers, they didn’t float disembodied in space, but they had an alien quality nonetheless, like the unidentified alien objects of yesteryear, and also something suggestive of a robot. She was a young woman, but mortal. Her eyebrows, on the other hand, seemed to have an immortal quality, as if they would outlast the human condition. They were like an uncanny glimpse of the future.

Ever since seeing that waitress’s eyebrows, I have sought to explain them, but it has not been easy. No man, least of all an English man, can walk into an establishment like the one we have here, called Brow Buzz, and ask one of the women to explain the modern eyebrow. It’s as if there is some unwritten etiquette that forbids such an enquiry. I might as well walk into one of the numerous nail parlours and demand to know if they really launder money there. Such things are like the Masonic secrets of the opposite sex. But somebody knows, I thought. Somebody could explain those eyebrows, how they are made, and why, and whether there are more on the way.

As it turned out, there were more on the way. Once one has noticed a thing, one tends to see it everywhere. Ever since that initial sighting, I have seen countless other examples. It’s exactly as if the dirty secret of places like Buzz Brow is this: that they are mass-producing eyebrows. Like Bond villains, these eyebrows will gradually take over the faces of half the world, attacking Bond where it hurts most, by targeting Bond girls. It’s a dastardly plan. These eyebrows are already obliterating the unique beauty of every face they settle on. The entirety of womankind will one day be overwhelmed by them. Every face will have frightening eyebrows that are out of proportion with the rest of the face, dominating their surroundings, until they merge into one huge monobrow of Frida Kahlo proportions. I knew it was already perfectly possible to see eyebrows like that roaming abroad, unhindered, a fact for which I held Cara Delevingne chiefly to blame. Yet the eyebrows I saw on that unseasonably warm February afternoon were not bushy; they were exaggeratedly modelled, as if painted on. Not a single hair was out of place. What could it all mean?

HIGH BROW CULTURE

She is older than the rocks among which she sits; like the vampire, she has been dead many times, and learned the secrets of the grave; and has been a diver in deep seas, and keeps their fallen day about her; and trafficked for strange webs with Eastern merchants; and, as Leda, was the mother of Helen of Troy, and, as Saint Anne, the mother of Mary; and all this has been to her but as the sound of lyres and flutes, and lives only in the delicacy with which it has moulded the changing lineaments, and tinged the eyelids and the hands.

These are the words Walter Pater used to describe the sublime Gioconda at the end of the nineteenth century. Very poetic, of course, but did he really see all that? She has such a kindly demeanour, nothing like a vampire, and what about that smile?

It seems odd, to say the least, that Pater doesn’t even mention the most remarkable thing about this portrait. Perhaps he was unable to see her properly, owing to the size of the crowd of admirers that day. If he had managed to elbow his way to the front, he might have observed that she comes across as benign, mild-mannered, even funny.

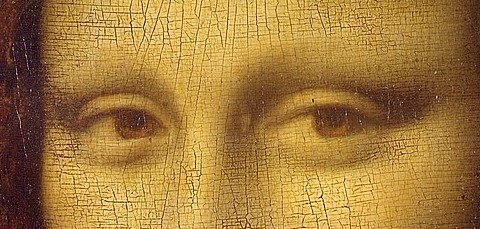

She sits there, quite prim, yet her smile is a candid one. She’s not what you might call a stunner, but she’s definitely not ugly. She has no moustache for a start; that was a mischievous addition the Dadaists came up with. Her nose is long but shapely. A fetching sfumato effect hovers about her features and she has (not so often remarked upon) no eyebrows. Say what you like about her, no one could call Mona Lisa ‘supercilious’. Only a nutcase could suspect that she smiles like that – without bearing her teeth – to conceal fangs.

On a visit to the Louvre in Paris recently, I decided to head straight for Mona Lisa. I wanted to home in on the pièce de résistance. Nothing less than the ‘vampire’ herself would do, so I hurtled through the galleries with indecent haste. The Louvre is a big place, but she is incredibly easy to track down, since no work of art in the entire building has her ability to draw a crowd. You know you’ve found her even before you see her face. You might even find her, as Walter apparently did, without getting to see her face. She is like that black hole the astronomers have recently managed to photograph – all you get to see is the event horizon, by which I mean the throng of people standing around her in rapt homage, careless of the danger of being sucked in.

I say ‘rapt’, but maybe I’m remembering a different crowd – the one that used to assemble around her in the days before the smartphone. Today’s digital crowd are there, in the room, with the Gioconda, but they do not have the same reverential attitude as the analogue crowd – their parents – used to have. Some of the digitals are holding their gadgets up and pointing them at her. Others hold theirs up too, but are facing in the opposite direction. Given how far some of these people are from their points of origin, you might think they would be slaves to the glamour of the masterpiece. She was painted hundreds of years ago, after all. She once smiled down from Napoleon’s bedroom wall. Her fame is such that, when they came to bestow some of their glitter upon her, she put Beyoncé and her husband in the shade.

Notwithstanding, the digital crowd turn their backs on her to take pictures of themselves standing in her presence, and by this gesture they tell us how truly dispossessed of glamour she has become. Not only is she reproduced on a mass scale, as we already knew, but she is reduced to an ornament in the background, behind other smiling people who are themselves reproduced on an unimaginable scale. She is beamed across the world in all directions, in an instant, a failed Renaissance photobomber peeking between more glamorous modern faces on Instagram. She comes across as dowdy and awkward. She looks out of place, even in what is uniquely her place. Maybe she should have shown her teeth, applied some makeup, prepared herself properly for the big occasion. She should have done more to appear ‘on fleek’. But that is the sad reality: Mona Lisa was always going to have a problem making a splash these days. It all comes down to her lack of eyebrows.

EYEBROWS IN THE AGE OF MECHANICAL REPRODUCTION

In Western society, women have long been on the receiving end of embarrassing amounts of praise. The tendency to depict them as goddesses goes back at least as far as Neolithic times. The versions favoured by the ancient Greeks were not so curvaceous, but they eventually prevailed over the more generously proportioned ideals of the cavemen.

During the Renaissance, this trend got a huge boost from the Italians, and specifically from Sandro Botticelli, whose svelte Venus stands on a big shell which is borne to the shore at Cyprus on a crest of foam. It’s one of the most familiar images of all time, therefore it’s quite unnecessary to reproduce the whole thing here. Besides, for the purposes of my theme, I intend to approach her warily, training my gaze exclusively on her eyebrows.

In a recent tour of Italy, Francesco da Mosto, strode right up to Botticelli’s Venus with total fearlessness. No iconic, universally famous beauty was going to frighten him. ‘Francesco’, as his adoring fans like to call him, is an enthusiast who excels in introducing the English-speaking world to the manifold delights of the dolce vita. He pootles around the Italian peninsula in his little car, singing operatic arias badly to himself, in a perpetual state of ecstasy at the food, the surroundings, the weather, you name it, that his beautiful country has to offer, exactly as if the tourism industry had yet to get wind of the place. It’s no surprise, therefore, that when confronted with the Venus on a wall in the Uffizi, Francesco immediately begins to gush about her charms.

Men’s attitudes in Italy are not so guarded as they are in contemporary Britain. Italian men who are possessed of old-world charm are as common there as intact medieval villages, whereas they are, it goes without saying, rare to the point of extinction on Britain’s inhospitable, tongue-tied shores. A certain kind of Italian man makes it his solemn duty to prove that the age of chivalry is not dead. He will greet a woman by kissing the upper part of her hand, an action not seen in Britain since the dawn of the Reformation. Thus, when confronted with the very symbol of feminine beauty, Francesco does not hold back. He confesses she is undoubtedly the most beautiful woman he has ever seen, then checks himself and says “Apart from my wife, of course.” Just look at her ever-so-slightly tilted face, he continues, her long neck, her elegant contrapposto posture. He simply cannot overstate her inexpressible beauty. “She is made for pleasure!” he concludes.

She is made for pleasure. Would it sound coy if I confessed that I don’t really know what this means? Because the obvious question here is whose pleasure we’re talking about exactly, her own, or that of Francesco? To be charitable to the Italian gallant, the answer would probably be a bit of both, but scratch a chivalrous gentleman and you’ll find a potential Berlusconi, avid to attend the nearest bunga-bunga party.

Maybe that’s just me being cynical. Besides, I don’t want to stray too far from the issue at hand, and therefore, confronted in my turn by the allure of Botticelli’s goddess, I shall quickly pass over the matter of her nakedness, or the fact that she is born fully post-pubescent. I shall even ignore the obvious improbability of surfing the waves on a giant scallop shell. Seafood – need I say more? Instead, like some blushing schoolboy who just walked in on the girl he worships in a state of undress, I shall avert my eyes and talk about something that cannot be considered illicit or saucy in any way, and which I dare say has never been mentioned before about Botticelli’s Venus. I mean, of course, her eyebrows.

Unlike Mona Lisa, Venus has eyebrows. Quite ordinary eyebrows at that. Anyone with the faintest claim to expertise on the matter of eyebrows can see that hers are unremarkable. They are slightly squared at the nose end and, after describing a graceful arch, they taper slightly at the temples.

These are not the kind of eyebrows to go viral. One wonders, frankly, who her influencers were. They are so understated, it’s hard to believe the people of her day ever appreciated eyebrows on a woman. Easier to assume that, when they looked at Botticelli’s eyebrows, men would sigh like a Shakespearian furnace, but for all the wrong reasons: “I’d prefer them non-existent, like Leonardo’s.”

Now, two-thirds of me belongs to a different century; the one just gone feels spookily present sometimes, like the phantom limb of an amputee. Being a visitor from the past, I decided to consult a book for enlightenment. If beauty was my enigma, then I wondered if Walter Benjamin could help. He was that rare thing, after all, a Marxist who was also an aesthete. The question of lost aura was one that had first occurred to him back in the interwar years when, faced with the triumph of photography and film, he foresaw the plight of Mona Lisa. Aura was his word for the uniqueness of the artwork. It also suggested a mystique of some kind, and a tradition that attached to its passage through time, the sort of thing Walter Pater was getting at. This was all there in the artefact. It had started as a cult object, put to use in rituals. Then it became more secular and appeared in exhibitions. Finally, the masses had got hold of it, robbing the artwork of uniqueness through endless reproductions.

In this way, the aura was dissipated. Mona Lisa acquired a moustache and was exposed to the indignities of mass reproduction. Benjamin might not have seen it coming, but Instagram would deplete the aura even further, emptying every last bit of it out of the image, which is why the crowds in front of Mona Lisa were distracted, by their own faces mostly, and bored by the real thing. She had become more familiar than their own faces. They’d seen her to the point where they could no longer see her, and familiarity had bred contempt.

I reread the famous essay, ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’, but I was disappointed. Despite his best efforts, Benjamin had allowed the whole mystery to slip from his grasp. Having seen the aura, he seemed to lose sight of it himself, and got carried away with ever more baroque observations on the nature of film. I would have responded in a melodramatic manner, tossing the book aside with disgust, had I not been reading the whole thing on a computer screen.

Instead, it was to my memory of Benjamin that I went for enlightenment, and two things I recalled from his personal reflections, though I had to trawl my unreliable memory to find them. The first was a marvellous line from his reminiscences of Berlin, when he spoke of trying not to look at beautiful women he saw in the park as he didn’t wish to intrude on their beauty, or something of this kind, and how the sidelong glimpses he caught inevitably led to the repeated experience of ‘love at last sight’. The second was his admission, somewhere, that it was the blemish on the beloved’s face that made it beautiful for the lover.

This was the holy grail. Beyond the mass production of the cosmetics industry, in the realms of actual beauty, the aura lived on in the individuality of a loved face, and not in its perfection, but in its imperfection, resided the attraction. I tried to hunt this little aperçu down, but in vain; it was lost forever in the old century along with two-thirds of my person. But he’d said it, I knew he’d said it, somewhere.

So, duly placated, I went back to the essay on reproduction and turning to the sixth section, instantly found this:

In photography, exhibition value begins to displace cult value all along the line. But cult value does not give way without resistance. It retires into an ultimate retrenchment: the human countenance. It is no accident that the portrait was the focal point of early photography. The cult of remembrance of loved ones, absent or dead, offers a last refuge for the cult value of the picture. For the last time the aura emanates from the early photographs in the fleeting expression of a human face. This is what constitutes their melancholy, incomparable beauty.

Bingo! That Walter Benjamin, he always comes up with the goods. The cult, and the aura it bequeathed to the image, may have deserted Mona Lisa, but that didn’t mean they couldn’t still be found, not in Snapchat perhaps, or any platform that erases the image soon after its conception, but in the good old traditional selfie.

PERFECTION

By now hungry for knowledge, like a crazed thing I decided to consult another book, this time in actual hard copy. It was not as incredibly old as Benjamin’s essay, but still, at some thirty years old, it belonged to an age before those with the questionable eyebrows were even a glint in their parents’ eyes.

The book was Naomi Wolf’s The Beauty Myth, first published in 1991, and it contained some difficult home truths on the role of men in the rigours of female beauty – so difficult that, as a man, I began to wonder if my curiosity about the appearance of modern women was part of the problem.

Wolf sees the insistent demand to be beautiful as the revenge Western men have taken on women’s emancipation. ‘It is hard to love a jailer,’ she says, referring to a time when these men kept women indoors, as housewives and child minders, ‘But it is not much easier to love a judge’. What right had I to set myself up as a judge of contemporary beauty, especially as, like a real-life judge, I was grotesquely old?

The book maintains that women are so oppressed by judgement of this kind that they’ll try anything to appease it, through tattoos, extreme diets, rhinoplasty, yet in a man’s world only the male is ever perfect. The female is left to wrestle with her imperfections, dressing and applying makeup, battling her age, seeing herself perpetually through the eyes of men – what Wolf calls inside-out eroticism – and imprisoned in the Iron Maiden of society’s pre-ordained notions of attractiveness.

That Iron Maiden made me wary. The idea recurred throughout the book; there was even a sub-section entitled The Iron Maiden Breaks Free, which sounded very gothic. It was definitely an instrument of torture or execution, possibly of German origin, but having seen one in a castle in Bohemia I couldn’t recall any resemblance to:

a body-shaped casket painted with the limbs and features of a lovely, smiling young woman. The unlucky victim was slowly enclosed inside her; the lid fell shut to immobilise the victim […] The modern hallucination in which women are trapped or trap themselves is similarly rigid, cruel, and euphemistically painted (p. 17)

It sounded a bit like the waitress, yet the Iron Maiden I’d seen was a very drab mechanism, a metal box with spikes on the inside. Oddly enough, this more delectable model really does seem to have been the author’s hallucination. The words ‘in which women are trapped or trap themselves’ are a bit of a giveaway too. Who in their right mind would ever climb into one of these things voluntarily?

It would be churlish, however, to argue with the book’s basic premise: that beauty is an imposition, and that women feel obliged to live up to its standards, imposed through a constant stream of images, many of them altered to achieve unreal perfection. She complains that

…we as women are trained to see ourselves as cheap imitations of fashion photographs, rather than seeing fashion photographs as cheap imitations of women (p. 105)

Nowhere in The Beauty Myth is there anything to suggest that women have been told about the lovable ‘blemish’ mentioned by Walter Benjamin. On the contrary, if he pointed it out, they would probably act swiftly to remove it long before Walter got a chance to pay a shy compliment.

There are different ideas of beauty in different societies. It’s well known that, for certain tribes in Africa, a plate in the lower lip or hoops around the neck are considered alluring. The effect is the same, however. Women are expected to go through pain or inconvenience in pursuit of the ‘perfection’ that beauty entails. This struggle to conform can easily lead to the horrors of anorexia and plastic surgery. The perceived blemish can be the source of body dysmorphia, which in its most extreme manifestations has led to suicide.

A passage describing a visit to a department store nicely illustrates the wider problem of striving for perfection. A woman enters the store from the street,

… looking no doubt very mortal, her hair windblown, her own face visible. To reach the cosmetics counter, she must pass a deliberately disorienting prism of mirrors, lights, and scents (p. 107)

Already in an advanced state of sensory overload, she looks about her:

On either side […] are ranks of angels […] the “perfect” faces of the models on display. Behind them, across a liminal counter in which is arranged the magic that will permit her to cross over, lit from below, stands the guardian angel. The saleswoman is human, she knows, but “perfected” like the angels around her, from whose ranks she sees her own “flawed” face, reflected back and shut out. Disoriented within the man-made heaven of the store, she can’t focus on what makes the live and pictured angels seem similarly “perfect”: that they are both lacquered in heavy paint […] the mortal world disintegrates in her memory at the shame of feeling so out of place among all the ethereal objects. Put in the wrong, the shopper longs to cross over.

Beauty, in this context, is synonymous with perfection. The drive is to achieve the perfect look, a drive that seemingly exceeds the rewards of love and sex. It’s a drive to belong, even to join the ranks of the blessed. If heaven, as the song says, is a place where ‘nothing ever happens,’ then that is part of the appeal, for here in this heaven the ‘shopper’ will no longer have to strive for the right look; she will have crossed over.

Sadly, this heavenly state is not for mere mortals and things will inevitably happen, hence the continuing agony. Could the problem be something to do with the ‘man-made’ nature of this heaven?

With the advent of plastic surgery, the true dystopia has begun. Women are no longer painted by male artists, nor always content with self-painting. Instead, they stand on the brink of being sacrificed to technology and going from ‘woman-made women’ to ‘man-made women’. Wolf tells us that at least one surgeon has totally reconstructed his own wife. Virtual reality and photographic imaging will, she thinks, ‘make “perfection” increasingly surreal’. She says surgeons in Los Angeles have already developed and implanted transparent skin through which the inner organs can be seen, opening up the possibility of ‘the ultimate voyeurism.’ Each to their own, I suppose.

Or perhaps not. There are times when the apocalyptic imagination can get a little, shall we say, hyperbolic. According to Wolf, we should really know by now, as the ‘millennium of the man-made woman will be upon us.’

ON FLEEK

Though the new millennium of the see-through ‘man-made woman’ has not come to pass, the age of the geek-made woman is well and truly upon us. On 23 January 2019, Elle Hunt reported in ‘The Guardian’ about the injurious effects of certain filters people were using to adjust images of themselves. These filters would change their complexion, alter the line of the jaw, smooth out any rucks in the facial carpet and enlarge the eyes. Those who suffered from a tendency to see every slight imperfection as a problem would then have a perfect image to send to potential suitors, only subsequently to disappoint the aforesaid suitors in the flesh. Some, to avoid such calamities, would even seek the help of surgeons:

The phenomenon of people requesting procedures to resemble their digital image has been referred to – sometimes flippantly, sometimes as a harbinger of end times – as “Snapchat dysmorphia”. The term was coined by the cosmetic doctor Tijion Esho, founder of Esho clinics in London and Newcastle. He had noticed that where patients had once brought in pictures of celebrities with their ideal nose or jaw, they were now pointing to photos of themselves. While some used their selfies – typically edited with Snapchat or the airbrushing app Facetune – as a guide, others would say, “‘I want to actually look like this’, with the large eyes and the pixel-perfect skin,” says Esho. “And that’s an unrealistic, unattainable thing.”

The basic error here is the insistence on one’s appearance being perfect, as if there was a manual somewhere entitled The Vitruvian Woman. One wonders when perfection ever got confounded with beauty. Nowadays, would Marilyn Monroe be allowed to keep the mole on her left cheek? Of course not, and by the way, she looked incredibly overweight in that pink number she wore in ‘Some Like It Hot’. No wonder she always ended up with the fuzzy end of the lollipop, her eyebrows were way too fuzzy.

Which brings me, by circuitous route, back to the topic I began with. Foolish of me to seek an explanation in books. Who reads them nowadays? One should always go to the most likely source, and the source of all insight is geek, especially for a living fossil such as myself, still capable on a daily basis of suddenly feeling I’ve been plucked from the depths of the sea (I’m thinking coelacanth, otherwise classified as ‘curmudgeon’), gasping for breath in the rarefied cultural atmosphere of our times. Go to the source.

So, I went to the source. Having chanced on the phrase ‘Instagram eyebrows’, I simply googled the phrase. The sensation was not unlike the one Ali Baba must have felt when he discovered a cave full of gold and precious jewels. There before me, in innumerable duplicates, were the eyebrows of my amiable waitress. There also, for this is social media we’re talking about, were numerous comments on the same, some laudatory, others denunciatory, a whole debate out there on whether to pluck, tattoo, thread, paint, manicure or otherwise customise one’s eyebrows.

But there was one video on YouTube that clinched the whole matter for me. A girl with somewhat Japanese features, unless that was my imagination, but a very broad Northern British accent, was giving a tutorial on how to create neater eyebrows and transforming her own from ‘sparse’ to ‘selfie-worthy’.

What she meant, of course, was on fleek. For lo, thy brow will be fainter at the nose end, and thicken even as it tapers towards the temple, for verily I say unto you (this is where it starts to get complicated, but in the immortal words of one Peaches Monroee): “We in dis bitch, finna get crunk, eyebrows on fleek, dafuq.”