ORIGINS OF THE WHIGS AND TORIES: ALL ABOUT THE ROYALS

The end of the English Civil War in 1651 witnessed the execution of King Charles I who was the King of the Kingdom of England, the Kingdom of Scotland and the Kingdom of Ireland. It should be noted that at the time England, Scotland, and Ireland were not united as one kingdom, but rather three separate kingdoms which were ruled over by one monarch. Following the execution of Charles I, the army general Oliver Cromwell ruled as a republican (though he was more of a military dictator) over England. He struggled to establish rule over Ireland and Scotland, which had more royalists than republicans. To secure rule over these Kingdoms, Cromwell tried carrying out armed attacks. In Ireland, there a was a faction of royalists called the Tories who would plan guerilla attacks on Cromwell’s forces, while in Scotland there was a similar group of republicans called the Whiggamores. Then, the Restoration occurred in which Cromwell was removed and Charles II (Charles I’s son) ascended to the throne. However, as Charles II left no heir, his brother James succeeded him as king. This was a problem since James was a convert to Catholicism and many feared he would take England back under the control of the Roman Catholic Church. As such, in 1688, a group of lords invited the Dutch Protestant King William of Orange to remove the Catholic James. These lords were insulted by royalists and were called Whigs (shortened form of Whigamores) by their detractors, they, in turn, called their opponents Tories, a reference to those guerilla fighters who were loyal to the old monarch. As such, the Whigs would become a faction that advocated for weakening the power of the monarch, while the Tories would become a royalist faction.

TRANSITION INTO CONSERVATIVES

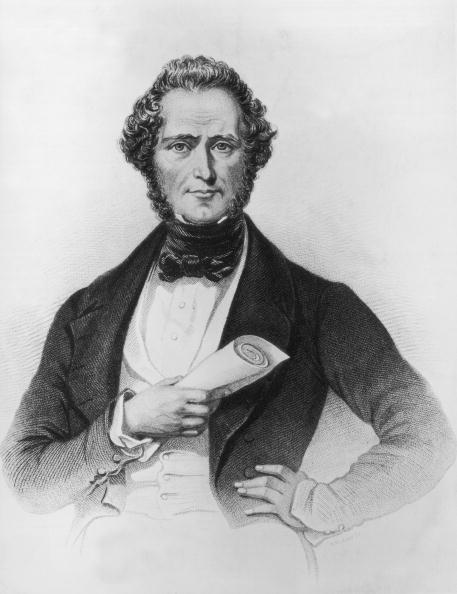

As noted, the Tories were the party that was more royalist and preferred maintaining a certain status quo within the state and government. However, by the 19th century, broader issues started to take center stage within the British government. For instance, there was the issue of expanding the franchise and more crucially Catholic Emancipation. For years, the British government had enacted several laws that were designed to oppress Catholics and those who were not members of the Church of England, for example the Test Acts made so that only adherents of the Church of England were allowed to hold public office or gain public employment and the Act of Uniformity ensured that the Anglican prayer practices were the only form of prayer that could be performed in public. Considering the fact that Ireland was a predominately Catholic nation, these anti-Catholic laws effectively oppressed the Irish by design. As the Whigs were pushing for more reforms, the Tories remained largely static. However, by the 1830s a huge wave of changes would occur within the Tory Party, changes that would effectively lead to a rebranding of the party as it would later transform into the Conservative Party. While the Whig Party was known to be the more progressive of the two ruling parties, it did not always have a progressive politician leading it; Whig Leader William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne, who was Prime Minister from July 1834 to November 1834 and again from 1835 to 1841, was anything but progressive. For example, while the Whig MPs in parliament were pushing for the Reform Act 1832, which would give more people the right to vote, he vehemently opposed it and only accepted it due to party pressures. On another unrelated note, Lamb was also opposed to the abolition of slavery within the entire British Empire. Ironically, King William IV was also opposed to the Whig’s reform proposals and he dismissed William Lamb as Prime Minister in spite of the fact that he too was not in favor of many of these laws. The King would then give Robert Peel, the leader of the Tories in parliament, the opportunity to form a new government. As such, Robert Peel started his process of reforming the Party; he knew that the Tories needed to move past its hard-line rightist state in order for it to be more appealing to the public. As such, he wanted to move the party to become more centrist, this was a smart strategy as it would accomplish the goal of appealing to more voters as well as keeping his base both in the public and within parliament. While the Ultra Tories, the Tories who opposed to all progressive reforms, were against Peel’s proposed new laws they would never in good conscience vote for the Whigs. Even before its official rebranding, many members of the public had already started calling the Tories under the leadership of Peel Conservatives. Peel had then called for a general election to be held in 1835 so that he could further consolidate his power, during his campaign he wrote the Tamworth Manifesto and had it published in newspapers. The Manifesto was meant to be for both the constituents of Tamworth and members of the public, as he laid down the policies he would follow as Prime Minister and more importantly it was the first manifesto of the newly branded Conservative Party as it became the basis by which the party would build itself on. The manifesto had also laid down reforms for expanding the enfranchisement and even had subtle hints of Catholic Emancipation (he appealed to the Church of England to reform itself to save itself) and most importantly it stated that he would keep the 1832 Reform Act. He also stated that he would be open for change which would, in his words, lead to "the correction of proved abuses and the redress of real grievances", a stark contrast to the Ultra Tories. However, things would eventually take a turn for the worse for Peel as one certain act he took as Prime Minister would eventually cause his downfall within Conservative ranks.

WHIGS JOIN FORCES WITH SMALLER FACTIONS

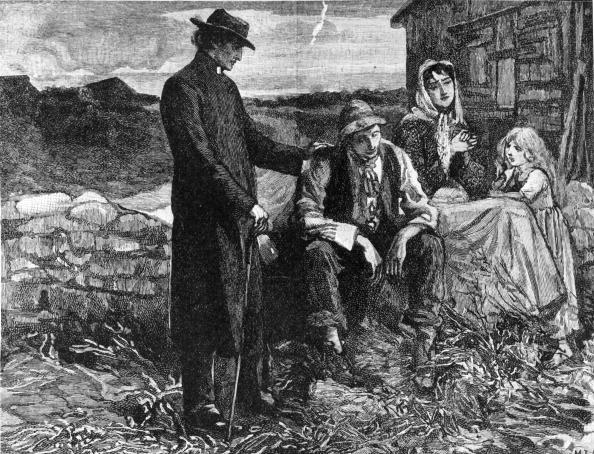

Ever since Peel’s reformations within the Conservative Party, the Whigs would grow even weaker. However, certain circumstances within parliament would pave the way for Whigs to also undergo a rebranding of sorts, albeit a much more drastic kind of rebranding. Going back to Robert Peel, one thing that would define his premiership and indeed his legacy was how he responded to the Great Irish Potato Famine. In 1846, both the Whigs and the Radicals (a faction within the parliament which pushed for radical changes and reforms) appealed to repeal the Corn Laws (tariffs that restricted imported food) as a means to help the Irish out of their misery. Controversially, Peel decided to join forces with the Whigs and Radicals and revoke the Corn Laws. While this decision helped Ireland it effectively destroyed his political career as it angered Conservatives in parliament and forced him to resign as Prime Minister in 1846. His resignation led to the rise of his long-time opponent Benjamin Disraeli who would become the new leader of the Conservatives. Meanwhile, Peel was forced to create his own faction in government comprised mainly of those who remained loyal to him and this faction was called the Peelites. The Peelites were not a small faction as during certain parliamentary sessions, it had as many as 80 members in parliament. So now, there were four different groups in parliament the Conservatives, the Whigs, the Radicals and the Peelites. Despite the fact that it was much more extreme than the mainstream Whig party, the Radicals had often united with the Whigs in opposition to the Conservatives. Meanwhile, the Peelites were somewhat of a balancing force between these two sides, in spite of the fact that it is principally opposed to the Conservatives.

During the 1850s, there was a lot of infighting within the Whig Party which had prevented it from becoming a strong opposition force. Both Lord Palmerston and Lord Russel wanted to lead the Whigs and both men despised each other; naturally, some Whig MPs were in favor of Palmerston while others wanted Russel to be the leader. Such circumstances did not help the Whigs in the 1859 General election as they lost 21 seats, while the Conservatives gained 34 seats; this of course meant that the government would remain a Conservative one. The next parliamentary session was meant to start on June 7 of that year, however, what would happen the night before can be described as nothing other than an extraordinary legal attempt of a power grab. On the night of June 6, the two diametrically opposed Whig leaders, Palmerston and Russel held a meeting with the Whigs, Radicals, and Peelites. In the meeting, both men promised that they would work together if all three factions united to table a motion of no confidence against the Conservatives, which they agreed on. From there the Liberal Party was officially born out of three factions all united under a banner of animosity towards the Conservatives. Then on June 7, the day the new parliamentary session was meant to start, the Liberal Party tabled the motion of no confidence and after three days of political battles within parliament, the Conservatives lost the vote of no confidence and a new Liberal government would be formed in its place with Lord Palmerston as Prime Minister and Lord Russel as Foreign Secretary.

FALL OF THE LIBERALS AND RISE OF LABOR

After winning the 1865 General election, the Liberal government enacted the 1867 Reform Act which gave more working-class men the right to vote. In theory, the act would help the Liberals as they would seem more appealing to a working-class electorate than their Conservative counterparts, however, the broadening of the franchise would eventually pave the way for another party that would appeal more to working-class men. In 1893, the Independent Labor Party formed as a result of a general belief that the Liberal Party was not doing enough for the working class. During the 1895 General Election, 28 Independent Labor candidates stood for parliament but none of them gained a seat. In 1900, a pressure group called the Labor Representative Committee (LRC) formed and subsequently stood in the general election of that year. It proved to be more successful than the Independent Labor Party as it gained the two seats it was campaigning for. Interestingly, both the LRC and the Liberal Party would start to cooperate after that election, and both agreed that only a Liberal candidate or a Labor candidate should stand in each seat against the Conservatives during the next election, in other words, Liberals and Labor would not compete against each other for parliamentary seats. 1906 was a breakthrough year for the LRC, as it gained 28 seats in the general election of that year; it later set itself as an official party rather than a pressure group and called itself the Labor Party. It became a force to be reckoned with during the 1910 election having won 42 seats in what turned out to be a hung parliament. Although the Liberals did not form a coalition with Labor, it still needed its support to oppose the Conservative MPs. Infighting within Labor Party during the First World War set the party back as some members supported going to war, while others opposed the notion. The Liberal Party was also split over the prospect of going to war as it was the traditional anti-war party, the Liberal government at the time eventually gave in and declared war on Germany on August 4, 1914. However, the Liberal government had major setbacks during the war, such as the 1915 Shell Shortage Crisis which forced it to form a wartime coalition with the Conservatives. The Liberals had other failings during the war which it never truly recovered from as it failed to ever return to its glory days. Labor, on the other hand, quickly regrouped in 1918 and published its own manifesto. The manifesto called for radical proposals such as industry nationalization and redistribution of wealth, proposals that solidified it as the party for the working class. It could be argued that Labor had the benefit of not gaining power too soon as its wartime party splits were largely ignored by the public and thus did not cause a massive decline for the party. The General Election of 1924 was Labor’s crowning achievement, the Conservatives gained the most seats having won 258 but they did not have enough for a majority. Labor came in second with 191 seats, while the Liberals had won 158 seats, as such they formed a coalition to command a majority and Ramsay MacDonald became Labor’s first ever Prime Minister.

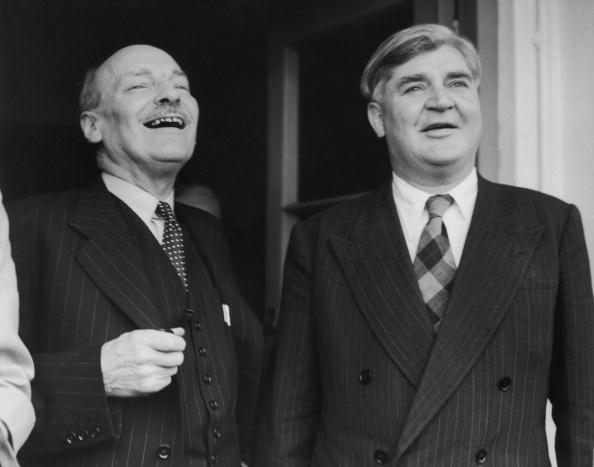

CLEMENT ATLEE’S WELFARE STATE

After World War II, wartime Conservative Prime Minister Winston Churchill ran against Labor leader Clement Attlee. While Attlee ran on an extensive platform of creating a welfare state that would help Britain recover from the war, Churchill did minimal campaigning thinking his war efforts were enough to keep him at 10 Downing Street. Attlee’s Labor eventually won a landslide victory and he and his cabinet began work on the welfare state. In 1948, Attlee’s Health Minister, Aneurin Bevan, established the National Health Service (NHS) which proved to be the only remaining legacy of Attlee’s premiership. Attlee would also implement a policy of nationalization as the steel, iron, gas, coal, electricity and railway industries all fell under government control. Attlee’s other policies were largely overambitious and unsustainable as such he could not create the welfare state he had envisioned.

WINTER OF DISCONTENT AND RISE OF THATCHER

By the late 1970s, Labor Prime Minister resigned and James Callaghan took over his post. Callaghan’s tenure comprised of a series of economic failings that dwindled Labor’s reputation for the next 20 years. In 1975, inflation had risen by 20 percent and the government had to raise taxes. By December 1976, Labor fell to global embarrassment as the government had to take a loan of 3.9 billion USD from the IMF, which was at the time the largest ever loan given by the IMF. The growing public discontent led strikes by many public sector workers such as garbage collectors and lorry drivers. At that point, the public thought that the country was in need of some strong medicine to cure its economic ailments. At the time, Margaret Thatcher had become the leader of the Conservatives, which caused the party to shift towards the harder right. By the time of the general election in 1979, the public had grown to see Thatcher as the right person to breathe new life in Britain. After becoming Prime Minister, Thatcher sharply decreased public spending and enacted policies that made it harder for trade unions to strike. The Thatcher years witnessed severe decreases in union memberships as she singlehandedly weakened the power they had over government. Thatcher also undid the nationalization efforts of Labor, as her government sold British Gas, Jaguar, British Aerospace and British Telecom.

TONY BLAIR’S NEW LABOR

Similar to how Robert Peel shifted the Tories to be more centrist, Tony Blair did the same to Labor in the 1990s. Tony Blair’s New Labor would no longer pursue policies of public ownership, which Blair deemed to be inefficient. Rather, the government would pursue free-market economic policies, which was believed to benefit both the economy and social wellbeing. Eventually, Blair resigned as Prime Minister in 2007 after ten years in power and appointed Gordon Brown as his successor. The Blair-Brown era caused many economic setbacks such as increased national debt, higher taxation and price hikes; this resulted in all-time low popularity for Labor which eventually led to a Conservative return to power in 2010.

The 2015 Labor leadership party election resulted in the victory of the socialist Jeremy Corbyn who aims to bring the party back to its socialist roots; however, the centrist elements within his party have been opposing his attempts.

PARALLELS WITH PRESENT TIMES

If this brief history lesson is to teach us anything, it is that the UK’s two-party system is not set in stone and many small pressure groups and factions have rocked the boat of British politics in the past. As it stands, Change UK, the Brexit Party, and UKIP are standing in the upcoming European elections which will serve as a litmus test on how popular they really are. If they make big gains, these parties might stand in the next general election and create major changes within British politics, just as the Peelites and LRC did in the past. Furthermore, Corbyn has proven to be quite resilient as Labor leader despite many setbacks such as the fact that many MPs within his party have resigned from Labor. While it is unlikely, Corbyn’s efforts might have a lasting impact on Labor and like Peel, Thatcher, and Blair, he might cause a significant political shift within his party.