With the release of L’Odyssée de la surpuissance (The Odyssey of Hyperpower), the French philosopher Gilles Lipovetsky has brought his exploration of lightness to a close, venturing into a sharper, more precarious intellectual terrain.

Published in January, Lipovetsky’s new work moves beyond his signature examination of societal fluidity and ephemeral consumption, turning instead to the ‘hyperpower’ bestowed by technology and artificial intelligence. He portrays contemporary life as a sweeping technological odyssey, one that places the very essence of human existence at stake.

This new turn invites a return to the long path Lipovetsky has traced since his earliest work. Before addressing ‘hyperpower’ and artificial intelligence, he laid the groundwork for reading the contemporary world through concepts that felt revolutionary at the time, from The Age of Emptiness to The Empire of the Ephemeral.

Between those beginnings and this latest book lie pivotal stations that shaped our understanding of femininity, consumption, and authenticity—stations I have travelled not only as a reader but as a translator who has lived with his texts and felt the depth of their transformations.

A civilisation of hyperpower

What Lipovetsky proposes in this work goes beyond routine sociological analysis. He describes a moment akin to the ‘Big Bang’, redrawing the contours of human civilisation. We are living, in his words, through an existential shift that unsettles the pillars of science, technology, the environment, and even individual identity.

In The Odyssey of Hyperpower, Lipovetsky sketches the features of this new phase, which he calls the civilisation of hyperpower—a stage in which every human limit is pushed to its furthest extent, with the unknown defining fields such as artificial intelligence, space exploration, and the manipulation of life’s very essence.

Within this imposing panorama, Lipovetsky does not overlook the paradox that has long accompanied his thinking. As capitalism expands to encompass the entire planet, turning every human desire and dream into a commodity, new and unprecedented fragilities emerge. While human beings possess the instruments of hyperpower, they find themselves constrained by environmental crises, by geopolitical insecurity, and by a decline in democratic vitality in the face of advancing nationalism and populism.

In Lipovetsky’s view, we are not merely witnessing shifting patterns. We are living through the birth of an unprecedented civilisation, compelling us to seek new keys to the future at a perilous crossroads of history and anthropology.

The unravelling of the age of lightness

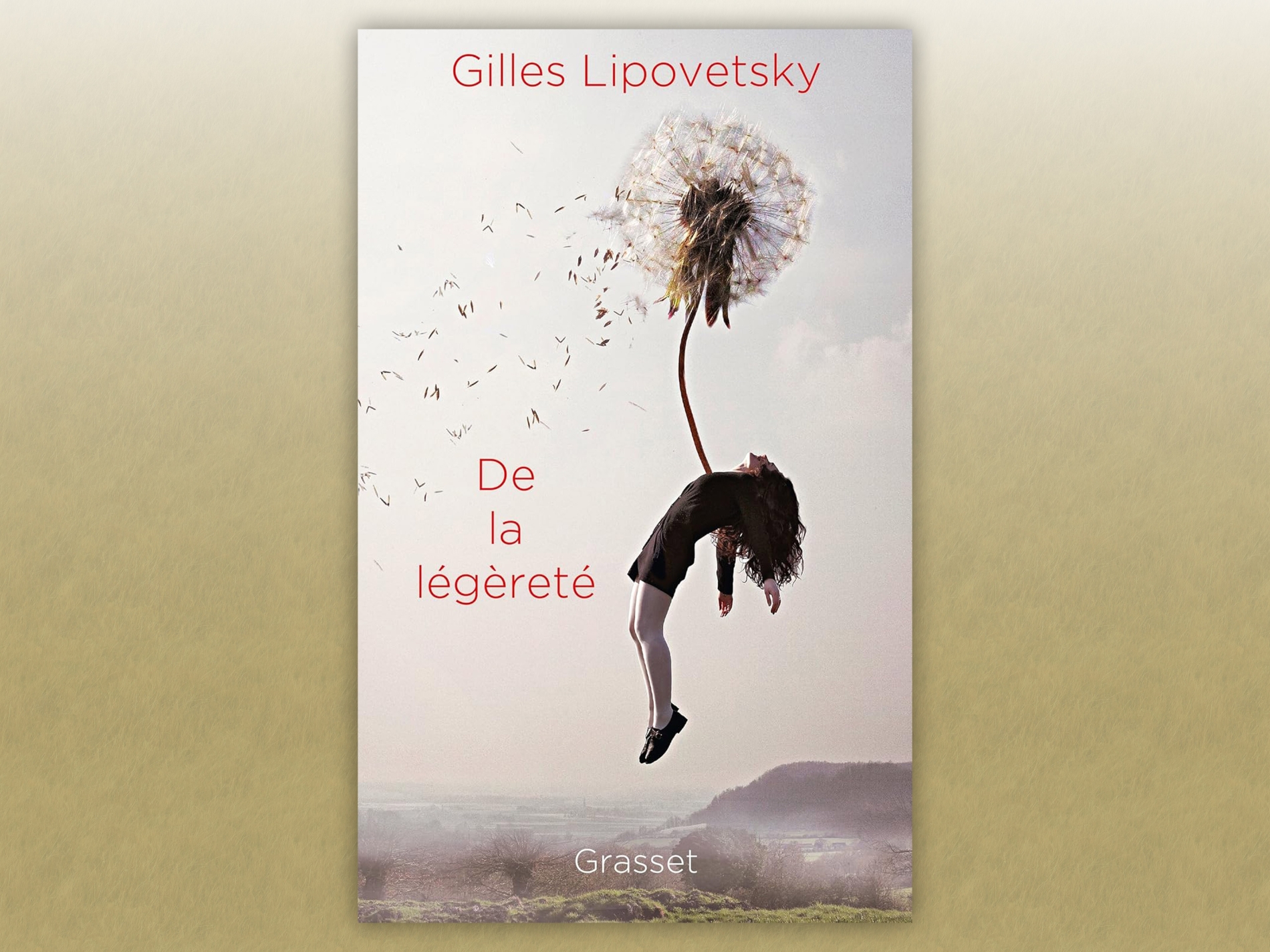

For years, Lipovetsky has analysed modernity and dissected the challenges of the postmodern human. With the world’s pulse accelerating to the point of breathlessness, power is no longer measured by stability but by flexibility. From his foundational book, The Age of Emptiness, to Lightness, Lipovetsky has held a mirror to our collective shift towards weightlessness. Yet this lightness, which promised liberation from heavy ideologies and repressive duties, has hardened into a new form of despotism—a soft despotism that obliges us to be cheerful, to consume, and to remain light at all times.

We live under the dictatorship of the smile, where sadness is a fault and depth obstructs both production and consumption. In this age, the individual is discouraged from self-examination or from dwelling on the wounds of existence. Every event must be swift, buoyant, and instantly disposable. We have shifted from the harshness of duty to the harshness of pleasure, with the contemporary individual coerced into happiness. The result is a fragile human being who flees any reckoning with the shadow that lies behind the veneer of consumption.