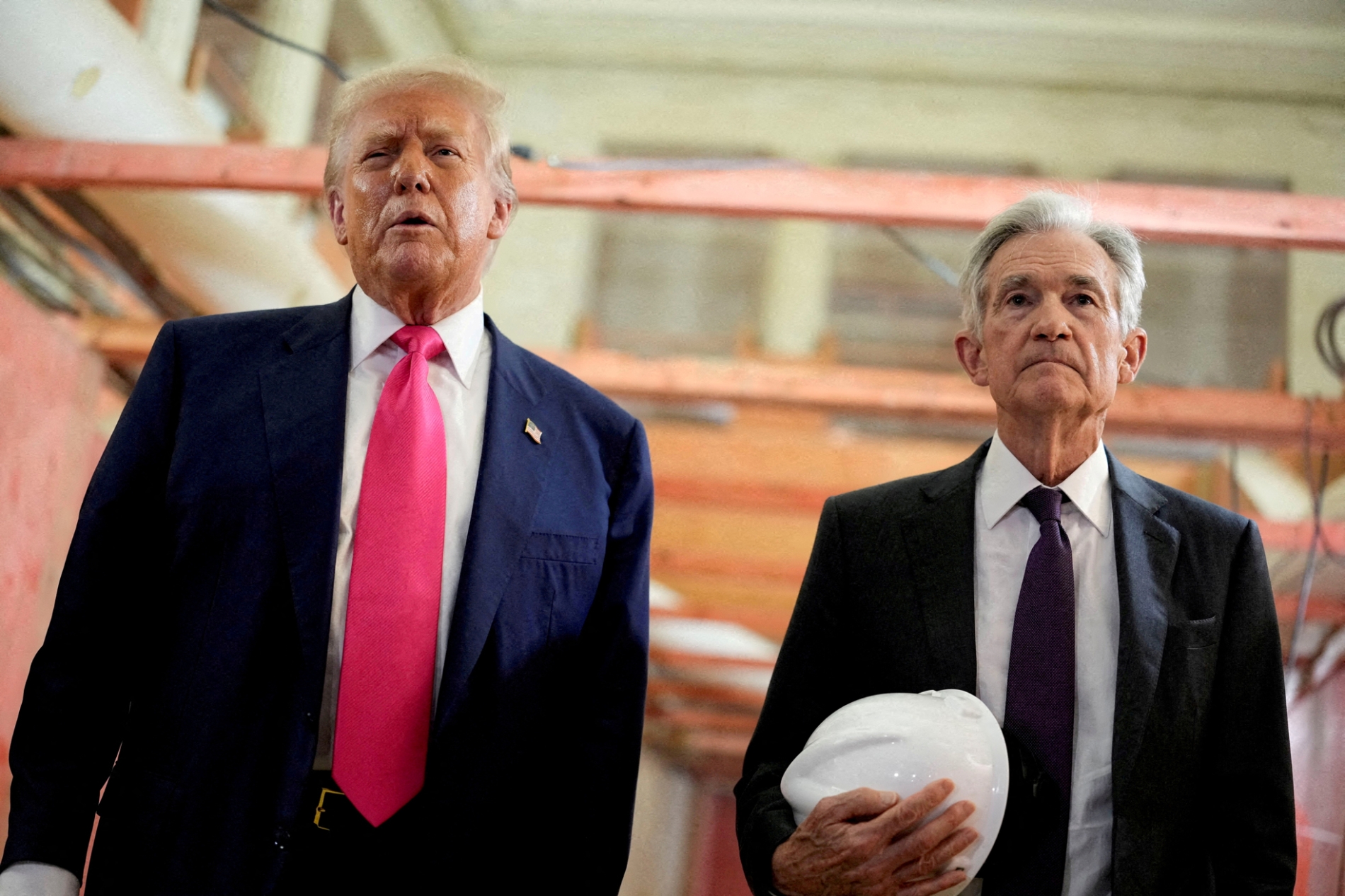

To say there is no love lost between US President Donald Trump and outgoing Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell is to understate the case, but in May their fractious working relationship will end when Trump appointee Kevin Warsh takes over at the Fed, assuming he gets Senate approval.

Trump has accused Powell of dragging his feet on interest rate cuts and of clinging to policies that stifle growth, but Trump looks at it from a political angle, whereas Powell is paid to look at things from an economic standpoint. Tension is added because the mid-term elections are approaching, and Americans are still struggling with the cost of living, which Trump knows will hit the Republicans at the ballot box.

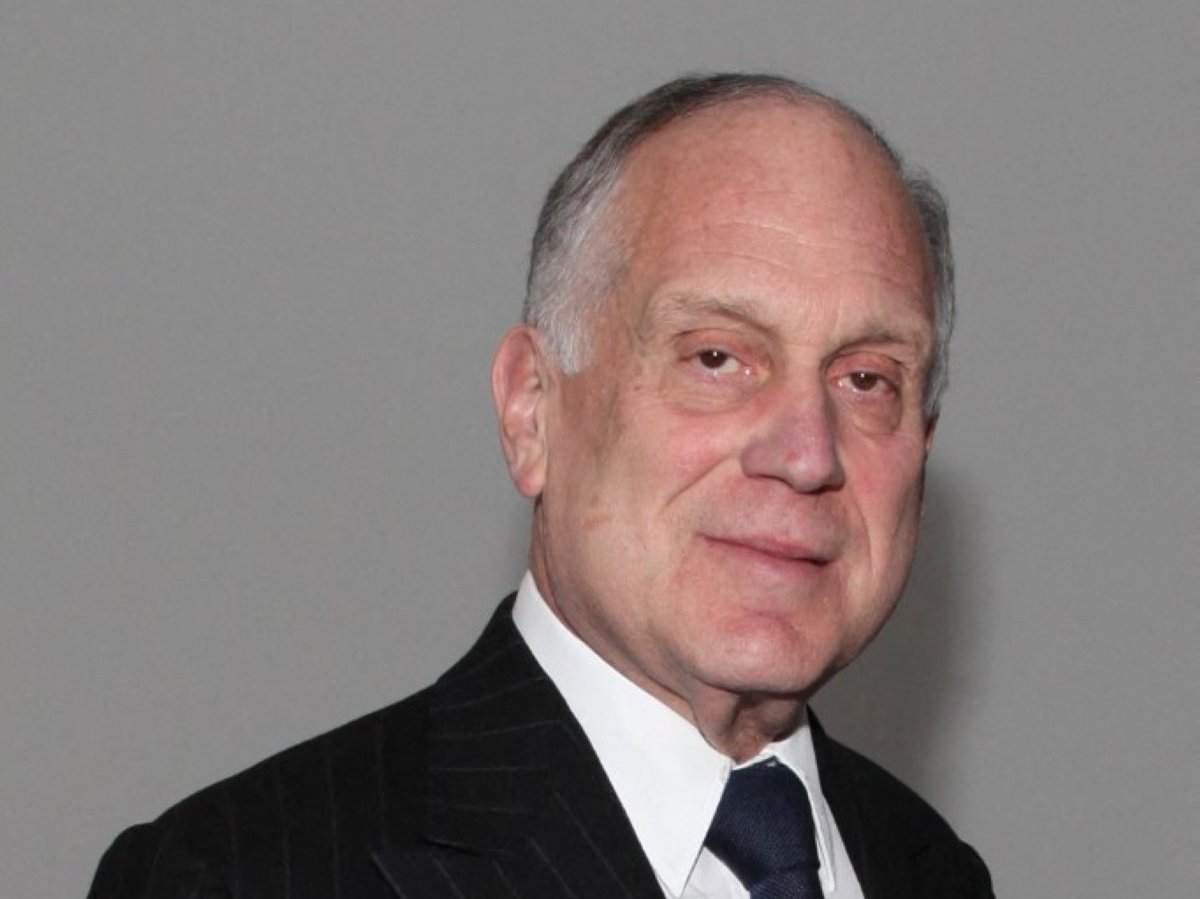

Despite a partial recovery in the labour market, Trump insisted that Powell’s monetary policy was blocking his economic agenda. By now, Powell is used to his swipes. Trump has denigrated the Fed chair in the media, suggesting he step down several times. Warsh, who is respected on Wall Street, is the president’s chosen successor, one with financial expertise, political instinct, and the ability to align the Federal Reserve more closely with Trump’s economic priorities.

Bessent's pick

Warsh is an insider. A former Federal Reserve board member, he has a strong academic record, deep experience in financial markets, and close ties to business leaders and Republicans. US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent oversaw the search for Powell’s successor, shortlisting Warsh and three others: Kevin Hassett, head of the White House National Economic Council; Christopher Waller, a Fed governor appointed by Trump in 2020; and Rick Rieder, a senior executive at BlackRock.

Once in post, Warsh would be independent, so could raise interest rates or keep them at their current levels, if he chose. At Davos, Trump expressed frustration with this, explaining how candidates “say everything I want to hear, and then they get the job, locked in... It’s amazing how people change once they have the job. It’s too bad. It’s sort of disloyalty. But they’ve got to do what they think is right”.

Warsh is seen as a leading figure in traditional Republican economic and financial circles. He spent 25 years at Morgan Stanley in New York, joining in 1995 before becoming a director of mergers and acquisitions. From 2002-06, he was an economic advisor to President George W. Bush at the National Economic Council. His portfolio covered domestic finance, banking regulation, securities policy, and consumer protection.

Bush nominated Warsh for the Fed’s board in February 2006, which drew criticism because Warsh was then only 35. He stepped down in 2011 following the shift toward a second round of quantitative easing, after the completion of the initial securities purchase programme and a return to more normal market conditions. He warned that further purchases risked fuelling inflation and undermining financial stability. Instead, he urged tax and regulatory reform to lift productivity and growth.

Using his connections

Well before the 2008 financial crisis, Warsh warned colleagues at the Fed that the financial system was facing a severe capital shortfall. At a Board meeting on 18 March 2008, he said the investment banking model was under threat and unsustainable. During the crisis and its aftermath, he was a key conduit between Fed chair Ben Bernanke, policymakers in Washington, and Wall Street.

Drawing on his Morgan Stanley background, Warsh offered critical insight into market conditions and helped shape efforts to support mergers, resolutions, and the orderly wind-down of troubled banks and institutions. He also represented Bernanke at the G20, later returning to Morgan Stanley as vice chair and has more recently lecturing at Stanford’s business school.