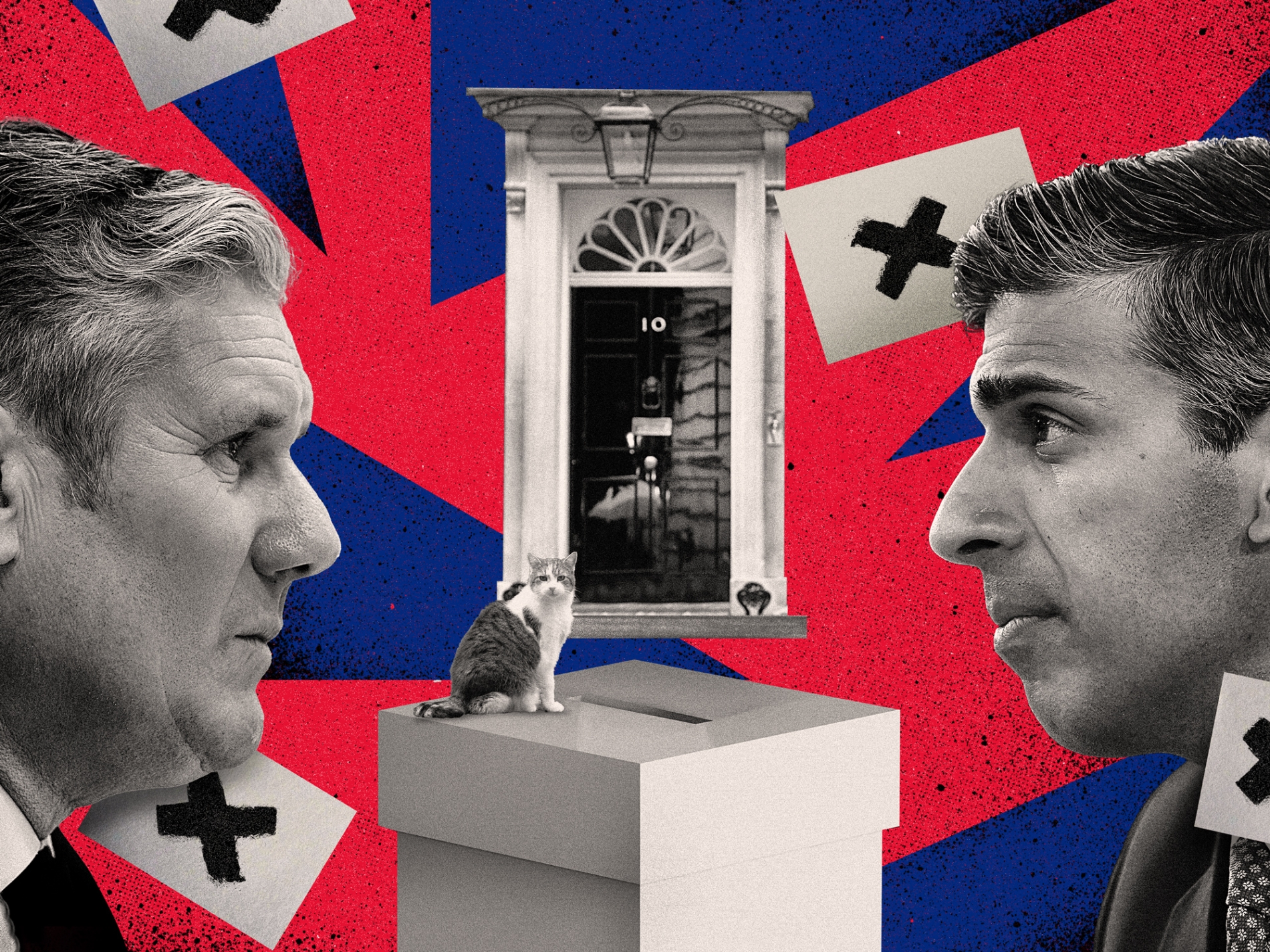

When Suella Braverman became the latest defector to join Nigel Farage’s Reform UK, her old party sneered that “The Conservatives did all we could to look after Suella’s mental health, but she was clearly very unhappy.” They later retracted the statement, claiming it was a draft sent out in error.

It might have arisen in an unguarded moment of exasperation. Reform has been embracing defectors from the Conservative party with such frequency that it now has more members of Liz Truss’s cabinet than there are on the Tory benches. Notable converts have included Nadhim Zahawi, whose spell as Chancellor lasted less than a week before the fall of Boris Johnson, and Robert Jenrick, Minister for Health under Truss, Minister for Immigration under Rishi Sunak, and the man Kemi Badenoch beat to the leadership.

Jenrick has displayed a rare gift for inflammatory language. On a visit to Birmingham, he complained that his was the only white face in Handsworth. There have been stunts too. During a fevered summer of St George flags, he was photographed hanging a Union Jack from a lamppost in defiance of an unpatriotic council. He is associated with the efforts of the previous government to control immigration. In April 2023, while defending their Illegal Migration Bill, he said that refugees crossing the English Channel ‘cannibalise’ communities by importing “different lifestyles and values”, which he said undermined “cultural cohesiveness”, and that the “nation has a right to preserve itself.”

It is fast becoming an issue for Nigel Farage that the sheer quantity of defecting Tories might have a similar effect on his own party. Reform has drawn much of its energy from opposition to the establishment and cocking a snook at the two-party system. With each new defection, the electorate is compelled to watch the old Tory party, the one they just rejected so comprehensively at the ballot box, reconstitute itself under a different name.

Read more: UK local polls: Labour and Tories bleed support from their respective bases

But the cannibal Tories are not just refugees from a failed project. Given the obvious ambition of ex-cabinet members—especially Jenrick’s—they threaten to upset the internal eco-system of the insurgent young party. Suddenly, even Farage looks in danger of being on the menu. Should he ever become prime minister, his role might be reduced to that of figurehead at best. If this is a real concern, he hasn’t shown it. The only hint was when he jovially ordained that the exodus must end by the spring.

As for Badenoch, her time as leader has not been hugely inspiring. For months she avoided policy statements and the party seemed intent on licking its wounds after its crushing defeat by Labour. This lack of energy on her part might partly explain the string of defections and her shadow cabinet’s increasing resemblance to what Disraeli would have called a range of exhausted volcanoes: ‘Not a flame flickers on a single pallid crest.’

However, in the case of Jenrick, Badenoch was able to relish a fleeting moment of revenge against the most prominent defector of them all. In a farcical oversight, Jenrick had apparently left his resignation speech where one of her loyalists could find it. She was thus able to push the traitor before he could jump. He was sacked by video.

Later that day, Jenrick was greeted by Nigel Farage as Reform’s latest scalp, but not before an embarrassing pause following the announcement, during which Reform’s luminaries had to let a collective smile die on their lips. Jenrick had lost his way and was wandering aimlessly around the wrong floor of the building. It was fitting symbolism. That very morning, Kemi had referred to him, with regal disdain, as Nigel’s problem now.

Since then, there has been the widely predicted defection of Suella Braverman, valiant champion of the Rwanda Scheme. Badenoch refrained from commenting on Suella’s sanity. She didn’t even refer to the former Home Secretary by name. Instead, she gleefully honed her disdain for defectors in general, saying: “To those who are defecting, who don’t actually disagree with our policies, I will say: I’m sorry you didn’t win the leadership contest, sorry you didn’t get into the Lords, but you are not offering a plan to fix this country. This is a tantrum dressed up as politics”.

For her part, Braverman gave Farage the kind of doting hug a prodigal daughter might give her indulgent father and declared that she had come home. It was a freighted phrase. The concept of ‘home’ could hardly be more germane to contemporary British politics. It was Suella who once said she dreamt of the day when asylum seekers— she had called them ‘invaders’—would be deported to Rwanda. Actually, of course, that had never been their home, but nor had this.

Others on the right are not bothered where undesirables are sent, just as long as it’s not to hotels where they are perceived as a threat to the local community. Even the people who have already made Britain their home may be in danger of losing it. Proof of the ugly tone of all this may be seen in the winsome guise of Amelia, an AI creation with purple hair. Her song ‘Sun All Year Round’ promises deportees better weather in the country they came from.

The image of Britain, with its orderly streets and its parliament, is entirely white. In contrast, their countries of origin are filthy and populated by brown faces. “You go live your life,” she croons as a deportation flight takes off, adding “I’ll hold you in mine!” as she cradles a white baby dressed in the Union Jack.

The casual nastiness of depicting the scenes of third world poverty to which these people will be ‘returned’ is made all the more callous by Amelia’s saccharin tones: “So let’s not be sad if we don’t meet again. You’ll be happy there, my friend, my friend.”

How much the Overton window has widened in recent months. Things are said freely now that would once have been considered beyond the pale. One of the Tory leader’s complaints, that the defectors ‘don’t actually disagree with our policies,’ may be illustrated by the fact that the Conservatives are talking about tracking down ‘illegals’ with a Removals Force. Back in October, Badenoch announced that this would be modelled on US ICE and would ‘deport 150,000 illegal migrants each year.’ She might hesitate to make that comparison now, after the events in Minneapolis.

In August, before the Tory leader had a chance to outline her plans, Zia Yusuf of the Reform party was speaking of Operation Restoring Justice, a five-year programme to track down, detain and deport all illegal immigrants. It would be known as UK Deportation Command, which sounded rather militaristic, but at least had the virtue of not sounding like a removals firm.

This is just one example of the way right-wing parties have begun cannibalising each other’s policies. They suffer from what Freud called the narcissism of small differences. Shared preoccupations include Britain’s membership of the ECHR, repeal of the Human Rights Act and curtailing indefinite leave to remain.