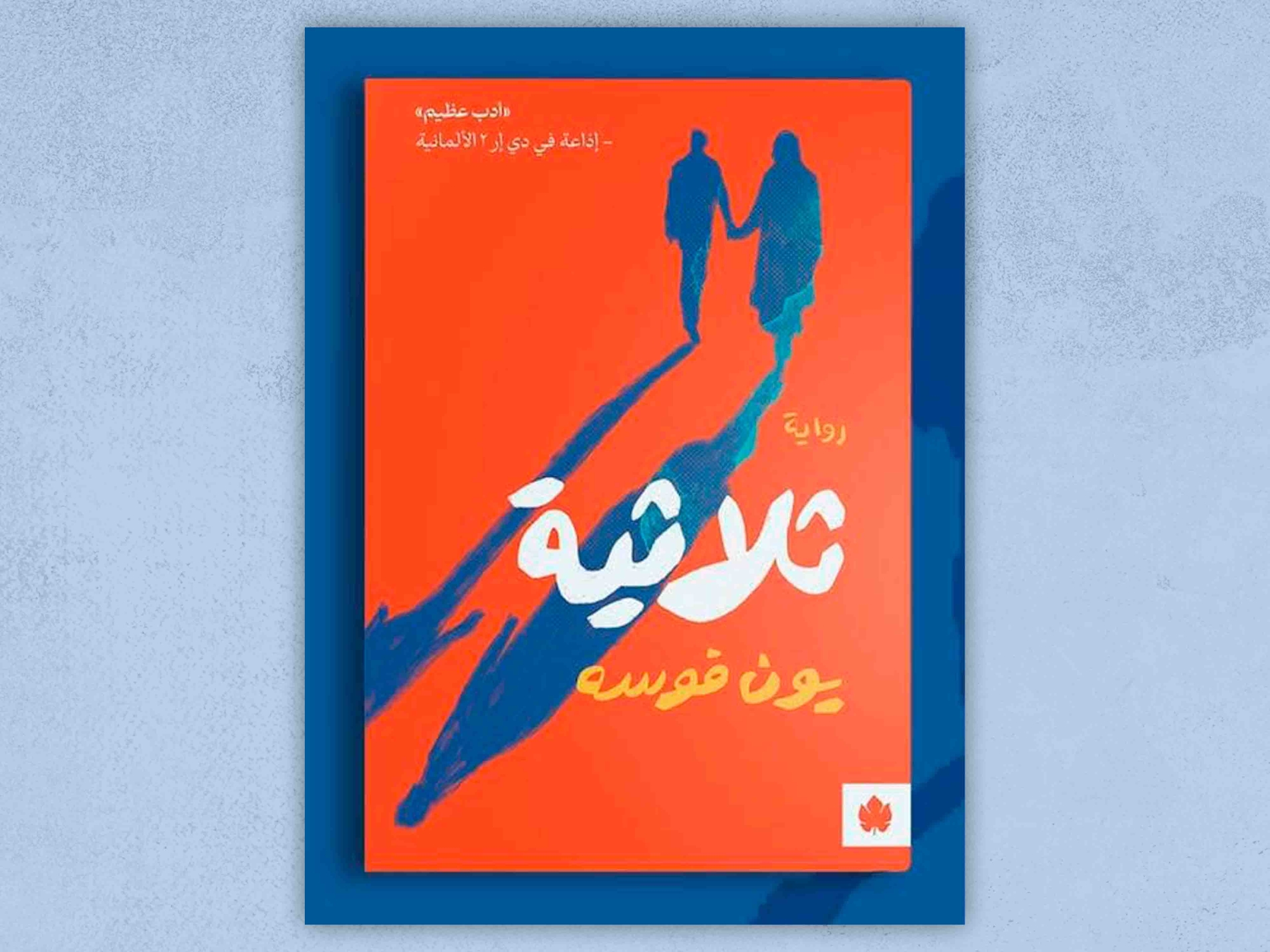

The Norwegian novelist, playwright, and poet Jon Fosse was in Saudi Arabia recently to discuss the art of writing at the King Abdulaziz Centre for World Culture (Ithra). Winner of the 2023 Nobel Prize in Literature, Fosse has written more than 70 novels, plays, poems, essays, and children’s books, and has been translated into more than 60 languages.

Born in Haugesund, a Norwegian city known for its cultural and musical festivals, Fosse talks to Al Majalla about silence, the formative role of poetry, his complicated relationship with theatre, and the importance of writing in Nynorsk. Below is the conversation.

Your play I Am the Wind suggests that silence has been a companion for decades. What, if anything, has it given you in return?

I began writing short poems and stories very early, around age 12. Poetry, or what one might call poetry, is the foundation of everything I write. I wrote my first novel, Red, Black, at 23, and published novels and poetry collections during the 1980s.

Later, I was asked to write a play. I had no intention of doing so, nor did I want to. But I was trying to survive as a freelance writer, and it was difficult; I needed money. So I sat down and wrote my first play, Someone Is Going to Come. It was an extraordinary experience, because I could write a word and then add “a short silence,” “a long silence,” and so on. Suddenly, I was able to create silence directly on the page.

Even after I had matured as a writer, I was still trying to reach silence, to make it speak. There is written language, but there is another language that exists above and below it: a silent language. It is this silent language that tells the truth. In the theatre, it was easier to achieve this, even though I was not particularly interested in it. I believe I also succeeded in doing so in the novel. My German translator often tells me that repetition in my novels takes the place of pauses in my plays, and I think he is right. In prose, pauses are created through repetition and subtle variation.

You published your first short story in a student newspaper. Did that experience influence your later literary career?

Yes. I loved writing, but it never occurred to me that I could become a literary writer. I thought I would work as a journalist for a regional newspaper. Then, at 20, while studying literature at the University of Bergen, I won a competition that encouraged me to write a novel. That award was a major boost. I sent the novel to a publishing house, and to my great surprise, they agreed to publish it. That came as a shock to me.

How do you view theatre?

When I wrote my first play, I almost hated theatre. Yet it turned out I could write plays. That’s how I became a playwright, without ever really becoming a ‘theatre person’. Although my plays have been produced extensively, with more than 1,000 productions worldwide, I always kept a certain distance from life on the stage. Things changed when I entered the world of theatre and got to know actors and directors. I felt I belonged to it in a way. I came to understand the value of what I call the ‘theatrical moment’: an intense, silent moment in which everyone senses the same meaning without a word being spoken. In Hungary, they call this ‘the passage of an angel on the stage’—a magical moment. For me, this is the essence of theatre.

From Red, Black to Septology, which explores identity, life, art, and silence, did the novel answer the questions that age raised for you?

No. I feel that I am simply... myself. When I write, I try to escape from myself, to move away from who I am and enter another world—the world of the text. Every work of fiction has its own form of being. I listen to what I have written, and also to something that has not been written. At a certain point, I feel the text already exists—outside of me, not inside—and I hurry to write it down before it disappears. It is a strange experience. Writing is not an expression of me; it is something else entirely.

Sometimes I compare myself to a painter or a musician. A painting ‘says’ something silently, yet even the painter does not know what exactly. One of my favourite painters is Mark Rothko. His paintings are silent, but they speak to me endlessly. I hope that my literature reaches others in the same way.