Graced by the presence of remarkable strangers, some cities have subsequently found their names inextricably linked to these fleeting visitors. Through their work, some writers, artists, and creators have a habit of transforming even the most unremarkable quarters into sites of cultural resonance, forever binding them in the imagination.

Like the ripples on a lake left by a departing flamingo, the effects can be seductive, magnetic, and radiant. Over time, such traces mean that the name of the city instinctively conjures images of its guest and their creations.

Many of these visiting, impacting artists did not seek exile or refuge in their temporary homes in foreign lands. Often, their stop-offs were not due to work, war, persecution, religion, or duty. Rather, most came about by chance, invitation, or urge. They arrived out of curiosity—to discover, roam, observe, and taste. Their stays were short-lived but their mark proved eternal. Some examples more vividly illustrate the phenomenon than others. Here, Al Majalla chooses three of Europe’s foremost artists who will now forever be associated with places in which they lived and created for a brief time.

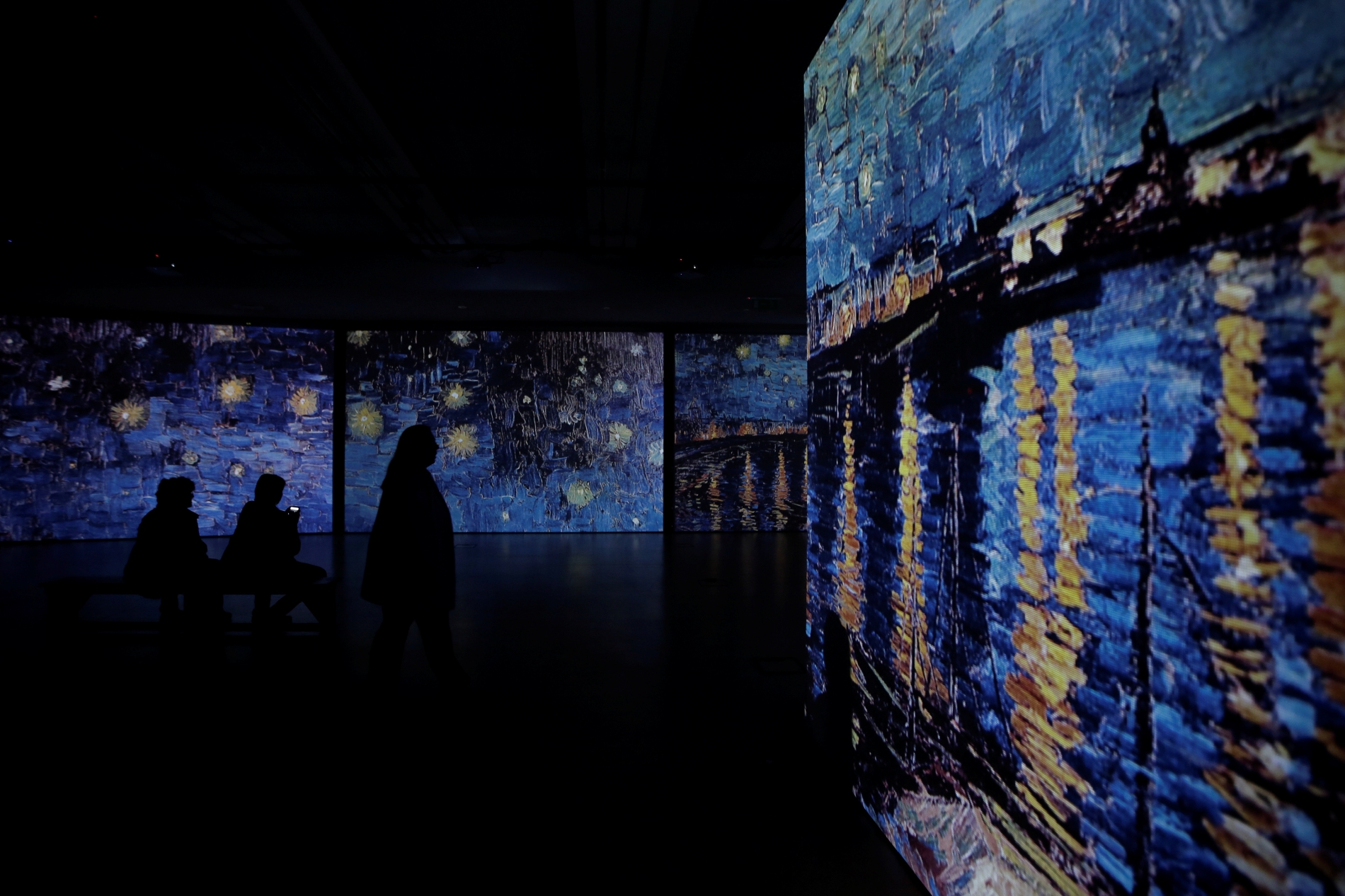

Van Gogh and Arles

During Dutch post-Impressionist painter Vincent van Gogh’s stay in the French town of Arles, from February 1888 to May 1889, he produced more than 300 works, including some of his most iconic: Starry Night Over the Rhône, Bedroom in Arles, Sunflowers, and Wheatfield with Crows.

Yet despite the prolific output, this was no starry-eyed stay for one of the most influential figures in Western art, because his 15 months on the Rhône River in the Provence region of southern France was also marked by mental ill health. His eccentricities disturbed the townsfolk, and they quietly conspired to have him removed. It culminated in his admission to the town’s asylum, an institution that would later bear his name.

Within Van Gogh’s work, Arles took on a yellow hue, yet yellow in his palette was never a simple token of joy. Rather, it bore the shadow of tragic endings. A strange, sudden, but lasting syndrome was taking hold as he dwelt in his solitary, yellow room, nestled in the intricate architecture of southern Arles.

Through the alchemy of colour—Van Gogh’s yellow in particular—the town gained a second visual identity. In his work, light became something magical, symbolic, aesthetic, and philosophical. Van Gogh expressed this vision in declarations as stark as they were poetic: “Two things stir my soul: the gaze into the sun, and death.”

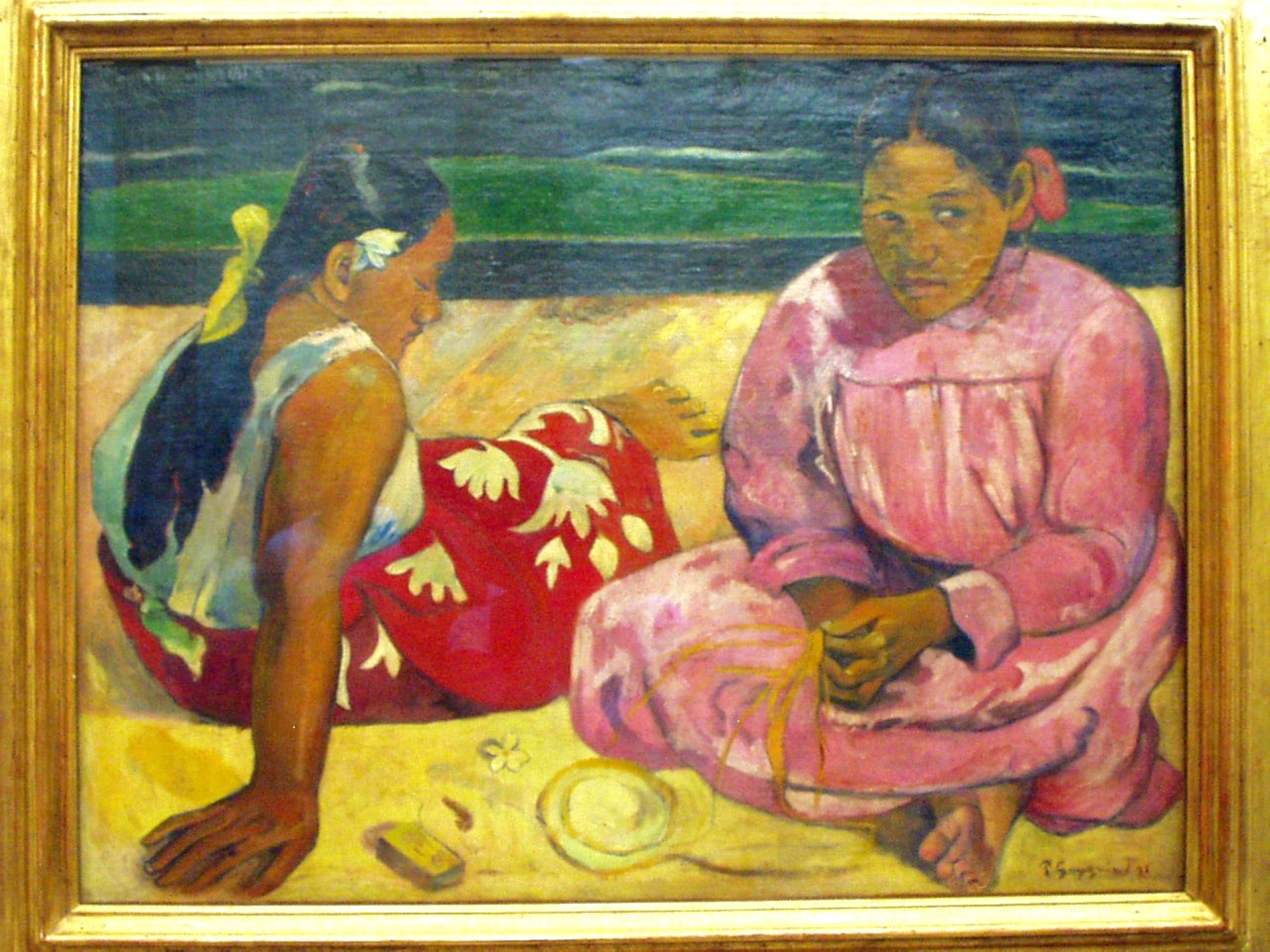

Gauguin and Tahiti

A similar transformation unfolded for Van Gogh’s friend, the French artist Paul Gauguin, albeit on the other side of the world, in French Polynesia. Gauguin—who was also a sculptor, printmaker, ceramist, and writer—spent a tempestuous period in Tahiti from 1891-93, during which his artistic vision flourished.

It was there that he created some of his most enduring works: Tahitian Women on the Beach, Spirit of the Dead Watching, Three Tahitian Women, and others that captured the island’s dreamlike tranquillity. No sooner had he returned to Paris than he felt the magnetic pull of the archipelago once more, departing again in 1895.

His was a deliberate escape—toward the raw, unfiltered beauty of a life grounded in primal vision, and away from the artificial clamour of Paris. It was, at heart, a repudiation of Western civilisation’s pretence and performance. Today, the name Tahiti evokes Gauguin almost instinctively, the two having become conceptually inseparable.