It Was Just an Accident is an Iranian tragicomedy revenge film that follows a group of ordinary people, all tortured by the same man during interrogations, now faced with their own sense of morality as they seek to take justice into their own hands.

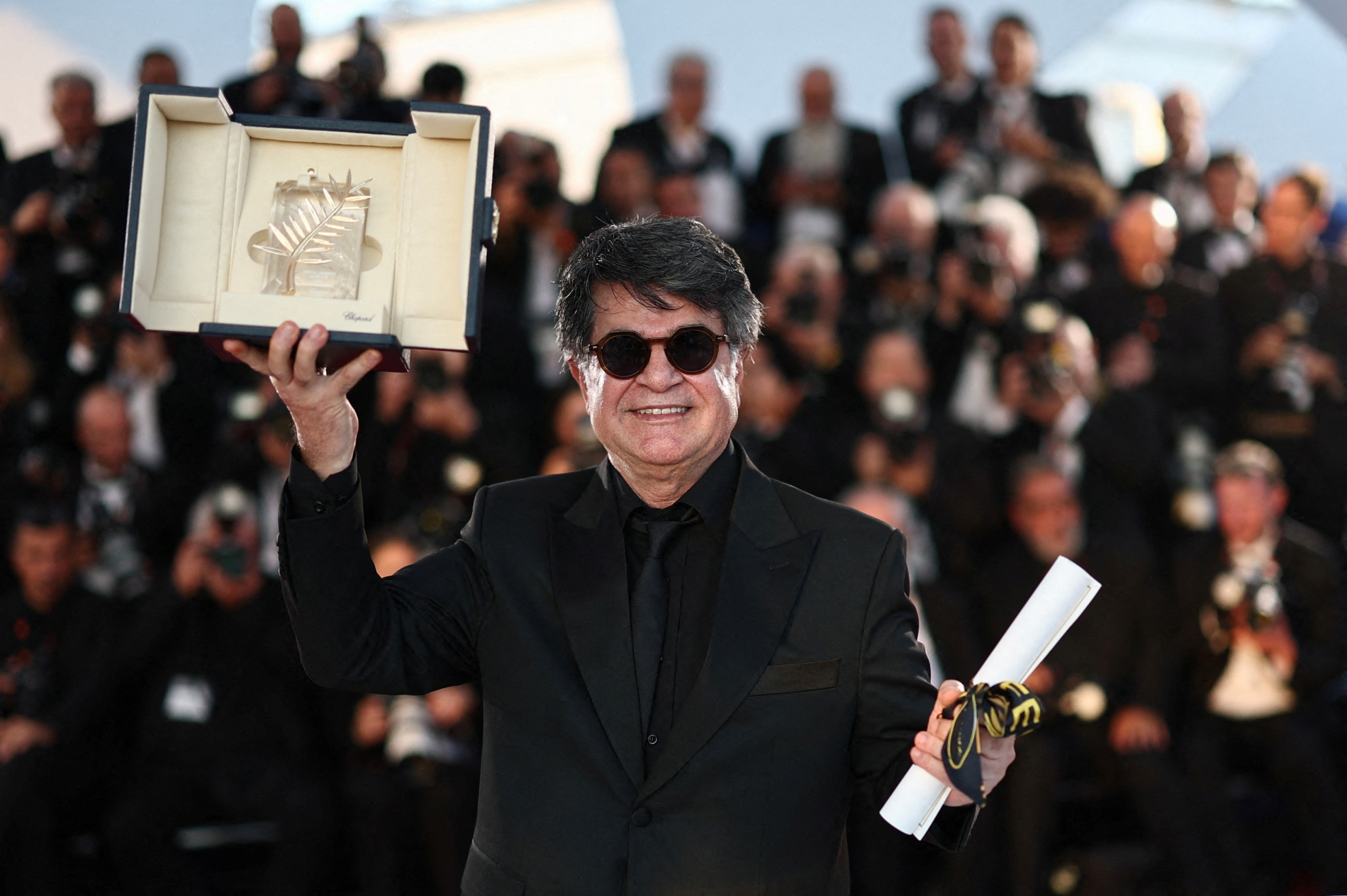

It is the eleventh feature film by director Jafar Panahi. As is common in his work, the film was made in secret to evade censorship imposed by the Iranian government, and it is the first film he has completed since his arrest in 2022, during which he spent seven months in prison before being released in early 2023 following a hunger strike.

Although Panahi has stated that he was not physically abused, unlike the characters in the film who disclose their experiences in chilling detail, the story feels undeniably personal. The different characters and personalities onscreen seem to reflect fragments of his own conflicted thoughts and emotions.

The “simple accident” refers to the moment a man, Eghbal, driving late at night with his pregnant wife and young daughter, hits and kills a dog. A red light shines on Eghbal’s face as he moves through the darkness, visually positioning him from the start as a suspicious, possibly villainous figure.

The accident causes his car to break down, sending him to a nearby garage, where Vahid, a mechanic speaking on the phone out back, overhears the squeak of the man's prosthetic leg. He recognises the sound instantly as belonging to “Peg Leg”, the man who tortured him years earlier.

The next day, Vahid kidnaps Peg Leg in broad daylight and attempts to bury him alive in the desert, only stopping when Eghbal pleads for his life, insisting he is the wrong man. The moment plants doubt in Vahid’s mind about whether he could, in fact, be innocent, he begins a desperate search for other survivors who might help identify him.

The first man he visits refuses to help, insisting that participating in revenge is beneath him and that Vahid mustn't stoop to his abuser’s level. Yet he begrudgingly directs him to Shiva, another victim.

Shiva, a photographer in the middle of shooting a soon-to-be-married couple, hesitantly agrees to identify the man locked in the back of Vahid’s van. Like the others, she never saw her torturer’s face and can only identify him through sensory memory—in her case, smell. She recognises the same strange, nauseating odour, but cannot be sure.

Chaos erupts when the bride reveals she, too, was a victim, and insists on joining them as they collect Hamid, Shiva’s former partner, who identifies Peg Leg by the scars on his leg and flies into a violent rage.