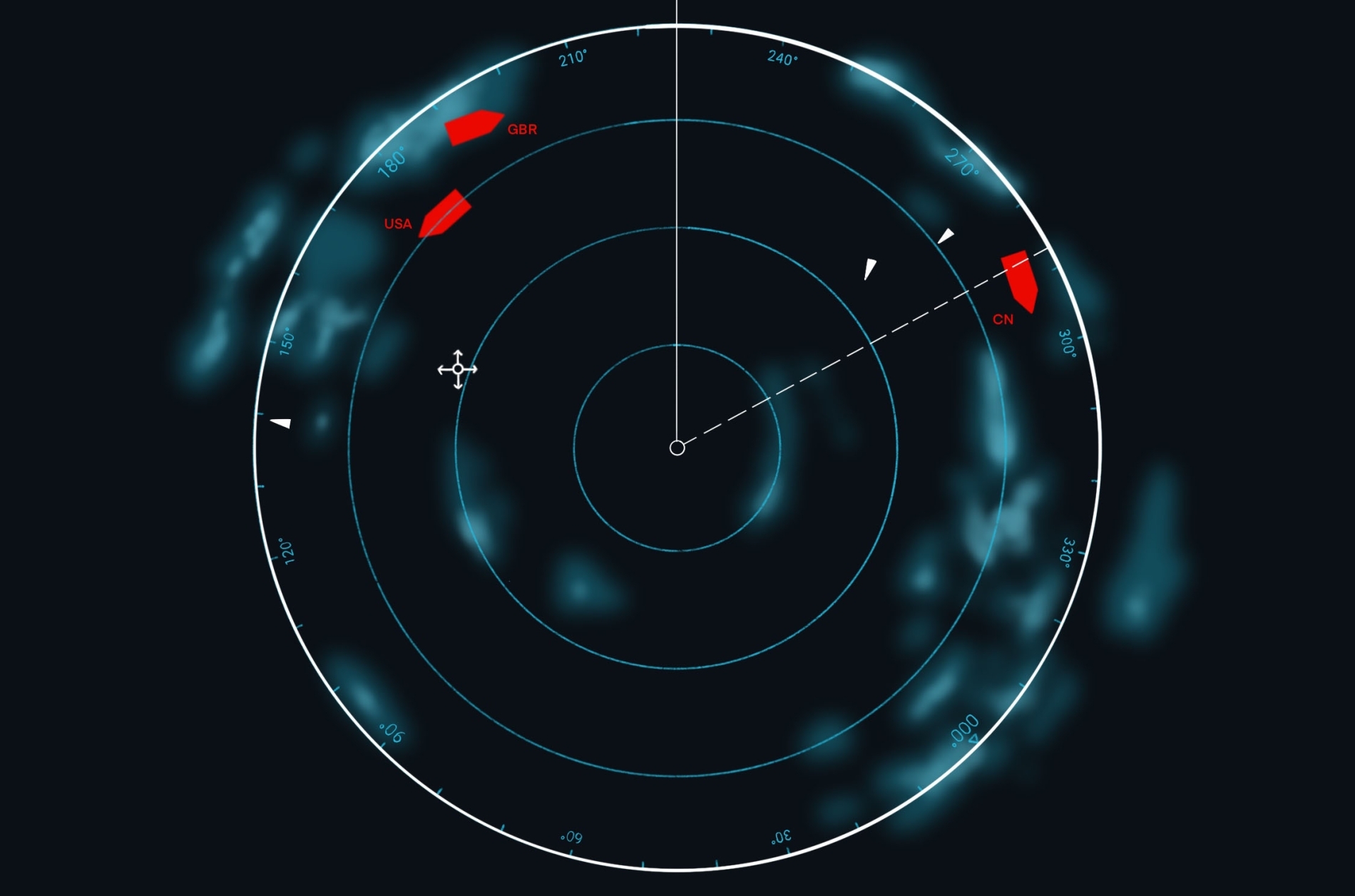

The world is witnessing an unprecedented convergence of international efforts to develop artificial intelligence (AI), alongside a deepening reliance on its applications. At the forefront, with its technology giants such as OpenAI, Alphabet, Microsoft, Meta, and Nvidia, is the United States, where innovation also flows from esteemed research institutions like MIT and Stanford University. China, meanwhile, hosts companies like Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent, and Huawei, under a centralised state strategy focused on controlling infrastructure and data.

Behind them is Europe which, by contrast, is prioritising the creation of a global regulatory framework—exemplified by the EU Artificial Intelligence Act—that seeks to balance innovation with protection. Gulf nations such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE have joined the race with multi-billion-dollar investments in data centres and research labs designed to attract global talent. Likewise, India is seen as a rising hub for software development and computational capability.

Global AI efforts oscillate between fierce competition and cautious collaboration. The Huawei 5G controversy in Europe exemplifies how technology has become a geopolitical battleground. Furthermore, the technology is no longer confined to civilian applications. Ukraine, for instance, has operationally deployed AI-powered drone swarms in warfare, showing how AI has become a strategic tool capable of reshaping global power dynamics.

Advantage and immersion

The race for expertise is intensifying, as is the scramble for semiconductors and infrastructure. The US continues to attract researchers and engineers from around the world, thanks to its robust academic ecosystem and generous funding, while China tries to repatriate talent through programmes such as the Thousand Talents Plan. At the same time, Saudi Arabia and the UAE are investing heavily in a bid to become magnets for global expertise.

Might the proliferation of AI herald a more collaborative world, underpinned by the interconnected nature of global tech ecosystems, or are we heading towards a more fragmented geopolitical and security environment that could reshape global trade and the economic order? The answer will have profound implications, because AI now permeates daily life in a trend that is only set to deepen.

Algorithmically powered devices and services often impact us without our conscious awareness. Images and words are suggested, our consumption patterns alter preferences, and vehicles grow more autonomous. This AI integration is accelerating, fuelled by partnerships between corporations and governments across complex, transnational supply chains.

A recent study by Gallup, in collaboration with the technology ethics organisation Telescope, found that around 64% of Americans use AI-powered products without realising it. This extends well beyond personal gadgets to encompass global infrastructure. It is estimated that the number of connected Internet of Things (IoT) devices will reach 18 billion by the end of this year and 39 billion by 2033. This surge reflects growing dependence on intelligent, interconnected systems—signalling a shift towards a digital network that is becoming inseparable from everyday life.

Borders and risks

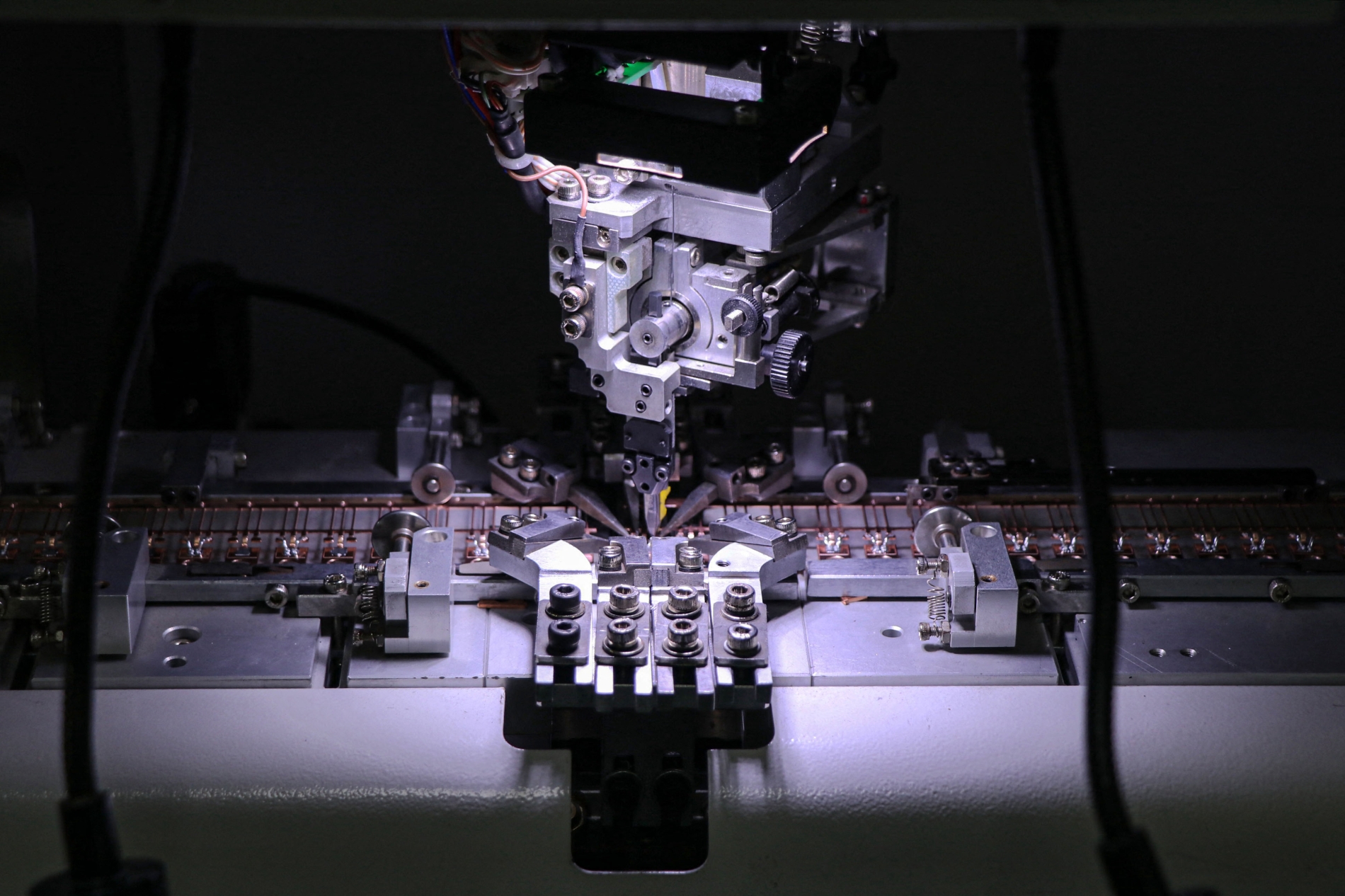

The autonomous vehicle industry offers a striking example of this interdependence. A single car may use American processing chips, Japanese and Korean cameras and sensors, and European software, with final assembly in Chinese or German factories. The end product is a testament to global economic cooperation—but it also presents serious security risks, as any component could become a vulnerability or backdoor for cyber intrusion and espionage.

Smart cities follow a similar path. In places such as Dubai, Singapore, and Shenzhen, traffic management, energy use, and emergency response systems rely on AI platforms integrated into IoT networks. This promises greater efficiency and resource optimisation, but it also tethers millions of lives to cross-border digital infrastructures that could be compromised or disrupted at any moment.

Healthcare and agriculture are likewise entering this realm of mutual dependence. Diagnostic tools that analyse medical imagery might be developed in California, run on European imaging devices, and powered by Taiwanese chips. In agriculture, robots monitoring crop conditions and irrigation schedules depend on a fusion of American, Japanese, and Chinese technologies.

In short, AI is no longer a localised innovation—it is a global ecosystem that necessitates economic cooperation, even amid intensifying political rivalries. Yet this very interconnectedness raises a more troubling question: will this ecosystem continue to serve as a force for improving lives, or could it become an instrument of surveillance and control, wielded by one power to the detriment of others?