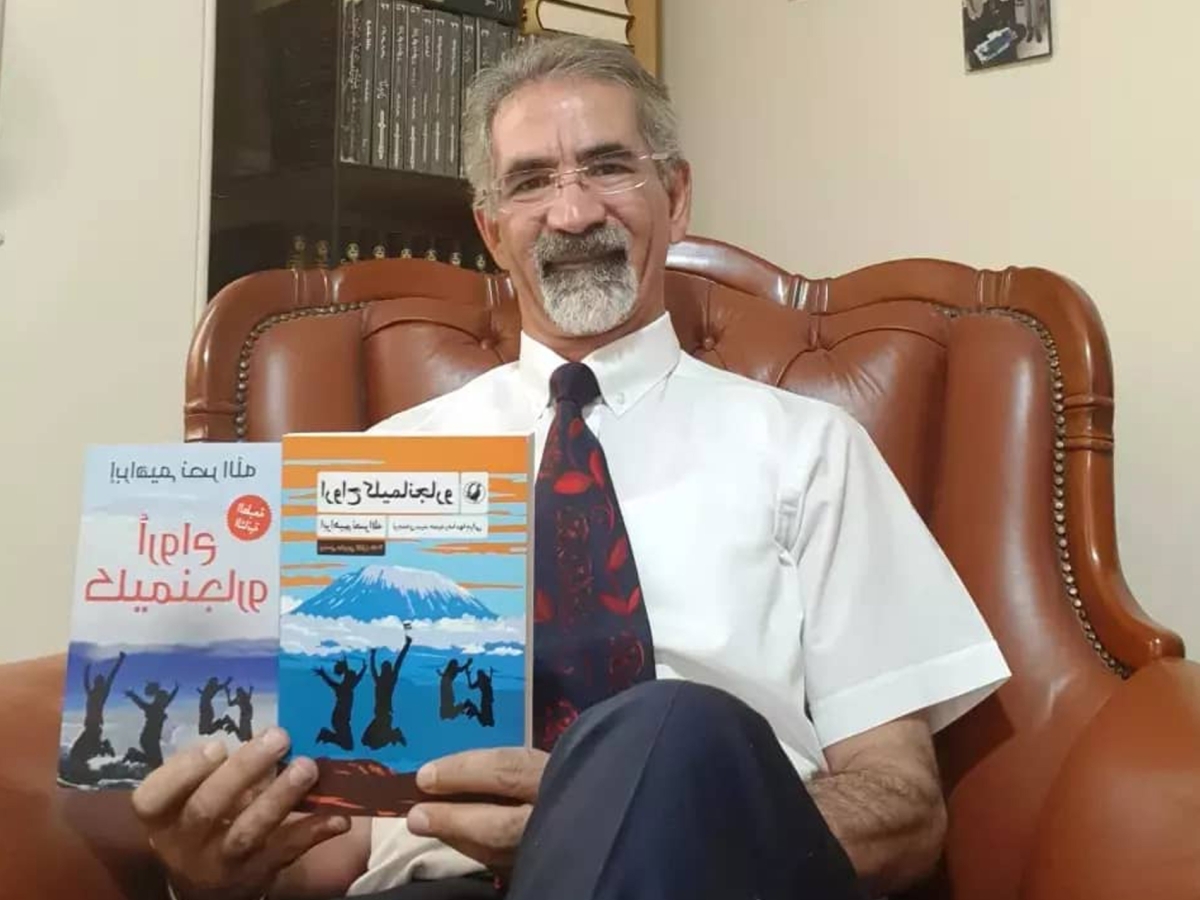

In the realm of translation, Iranian writer and translator Hamid Reza Mohajerani stands out as a bridge between Arabic and Persian literature, owing to his extensive work translating contemporary Arabic novels into Farsi. Among the Arab authors whose works he has translated are Amin Maalouf, Elias Khoury, and Waciny Laredj.

Speaking to Al Majalla, Mohajerani explained how he saw the translator’s role in fostering cultural exchange between Arabs and Persians, two geographically adjacent yet culturally distinct societies. He also mused on the challenges of translating Arabic texts into Farsi, alongside broader issues relating to the state of culture, censorship, and intellectual life in Iran. Here is the conversation.

Why did you pursue the field of translation?

From an early age, I was captivated by both nature and literature. I ran barefoot through the meadows by the river near our village, reciting verses from the great Persian poets. Although I was too young to fully comprehend the meaning, I instinctively felt that literature and poetry were sacred, offering a sense of peace and serenity. My passion deepened after attending congregational prayers at our village mosque, where I heard the imam reciting verses by the lyrical poet Hafez of Shiraz. It made me realise the intimate connection between heaven and earth—a thread linking the cosmos to poetry.

How did your relationship with the Arabic language begin?

Arabic and Farsi are like adopted sisters. There are two wings of the bird that are Islamic civilisation. Throughout the history of this civilisation, we encounter numerous brilliant figures who mastered both languages, including Avicenna, Nur al-Din Abd al-Rahman Jami, Jalal al-Din Rumi, and the Turkish Sufi scholar Sadr al-Din al-Qunawi. Each left a lasting legacy in science, literature, medicine, and philosophy.

I consider myself a child of both Persian and Islamic civilisations. You need to master both Arabic and Farsi to truly engage with the likes of Marzban-nameh, The Complete Works of Saadi, The Divan E Shams E Tabrizi, The History by Abu’l-Fadl Bayhaqi, or The History of the World Conqueror by Juvayni. This was a powerful personal motivation for me to learn Arabic. Arabs need to learn Farsi and Persians need to learn Arabic because both are part of a shared heritage: the Islamic civilisation.

Did you face any challenges when translating from Arabic into Farsi?

Certainly. Despite shared elements between the two languages—whether in vocabulary, structure, proverbs, or poetic expression—there are deep differences that arise from the distinct cultural and traditional landscapes of Arab and Persian societies. Cultural ties between the two date back to the Sassanid era (226–651 CE) and continue to this day.

The language of the novel is not merely literary; it is something greater. It is the language of love. This often draws me back to the works and verses of leading figures in Persian literature, such as Mawlana Jalal al-Din Rumi, Hafez of Shiraz, and the great humanist poet Saadi of Shiraz. I turn to their poetry and timeless wisdom to help convey the deeper meanings embedded within challenging texts.

How do you handle Arabic words or expressions that lack a direct equivalent in Farsi?

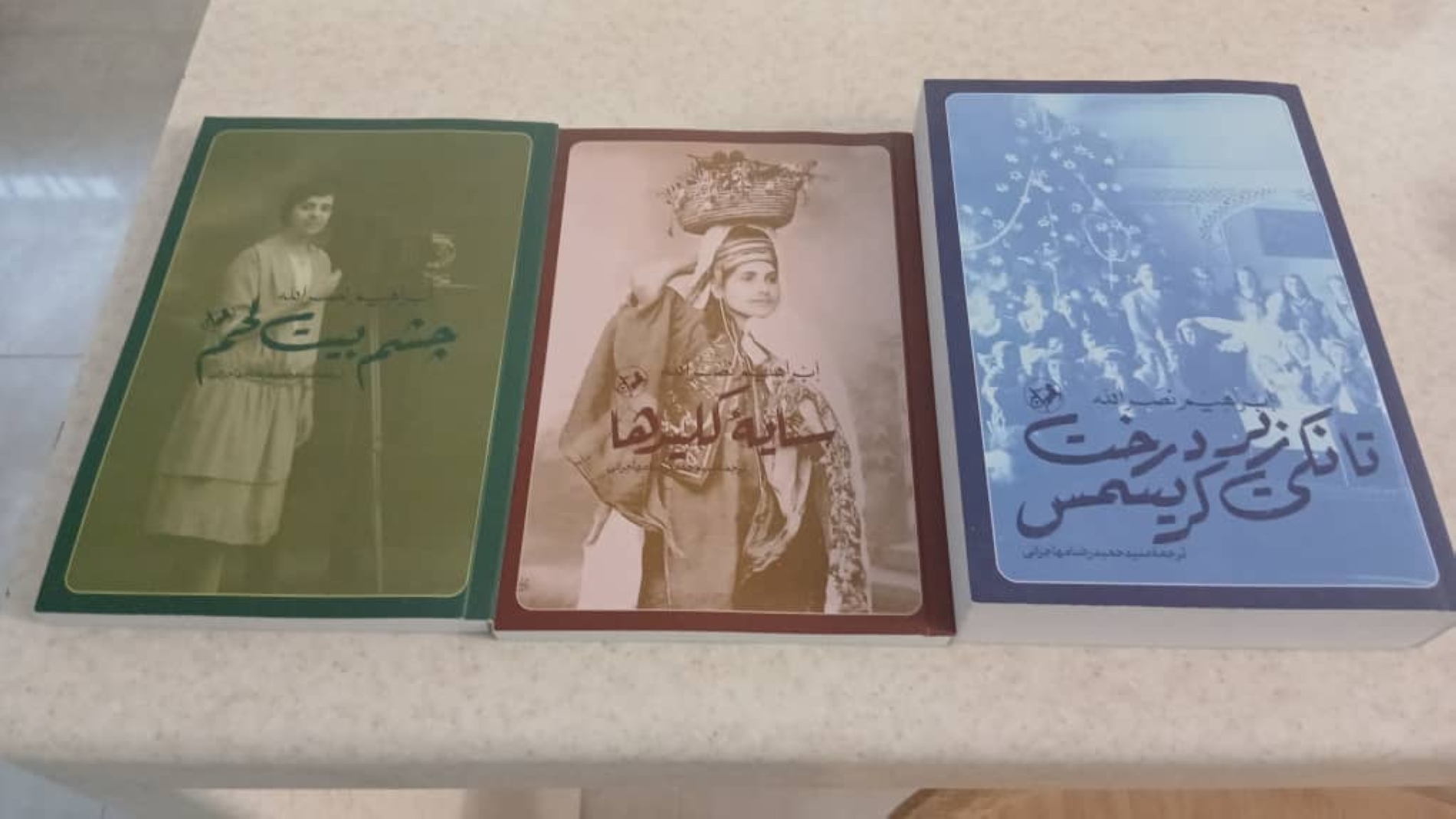

I translate colloquial or dialectal phrases in novels using the vernaculars spoken in southern Iranian regions, such as Khuzestan and other areas inhabited by our Arab compatriots. For example, when translating The Bird Tattoo (2020) by Iraqi author Dunya Mikhail—which is set in Kurdish regions of Iraq, including Sinjar—I incorporated Kurdish terms and referenced local traditions, which I then explained in footnotes. This let me highlight certain cultural and ethnic commonalities between our Kurdish compatriots in western Iran and the Kurds of Iraq.

Do you use electronic translation tools? If so, to what extent?

I never rely on AI-generated machine translation. AI (artificial intelligence) is a product of the human mind; it can never rival it. I advise my students not to depend on machine translation, as it merely provides literal word equivalents, with no regard for the emotions or nuances, elements shaped by human intellect. This is why artificial translation will never threaten the human mind or its spirit.

You’ve translated works by numerous Arab authors and thinkers. Is there a particular text that left a profound impact on you?

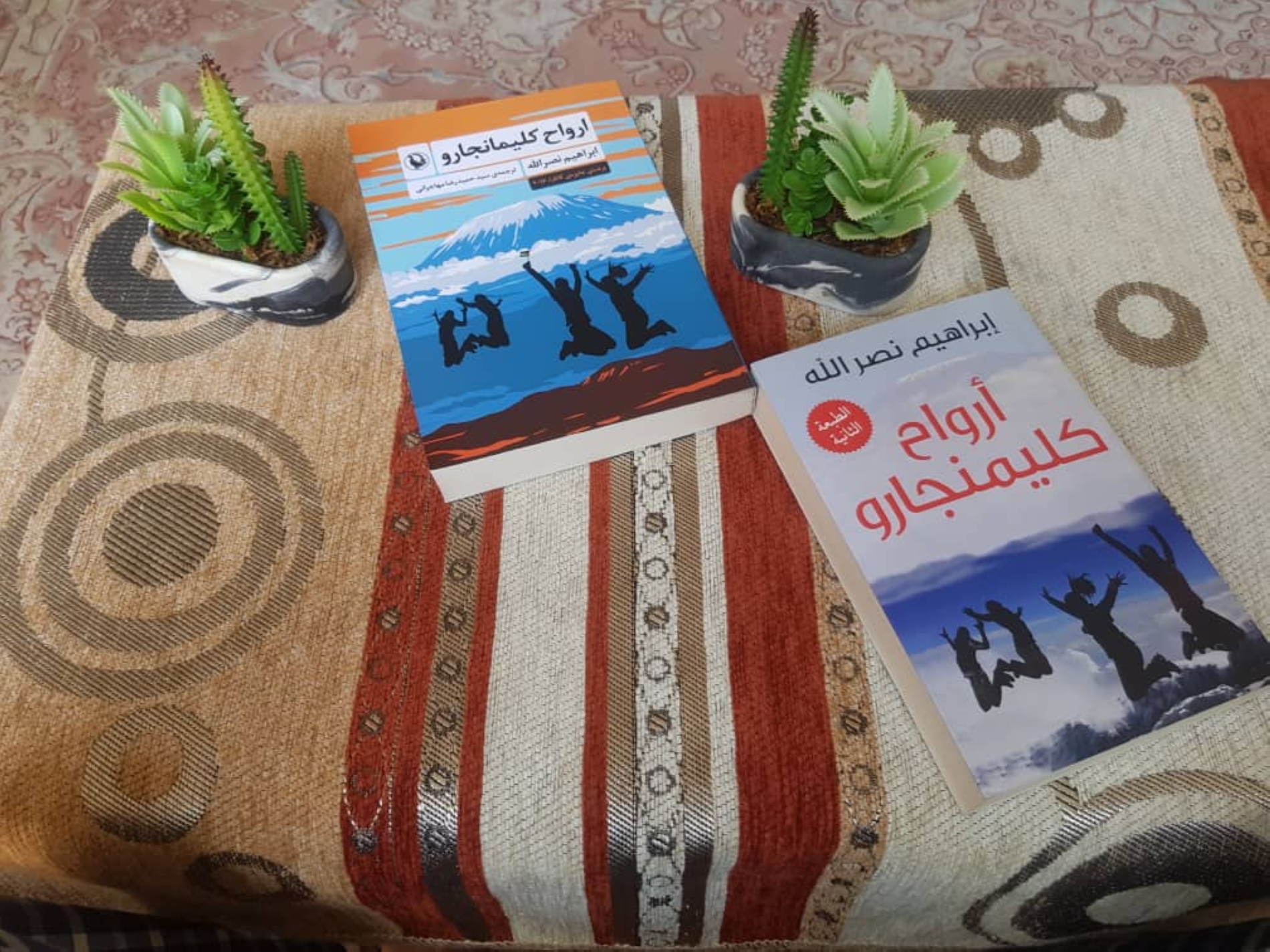

Those whose works I have translated are pioneers of human thought, bright stars in the sky of Islamic civilisation. When I first read The Guardian of Shadows (2011) by Algerian writer Waciny Laredj, I read it three times. By this repeated reading, I was able to fully grasp its depth and uncover the many profound layers of meaning. After translating and publishing the novel, we witnessed a strong and enthusiastic response from Iranian readers to this remarkable work.