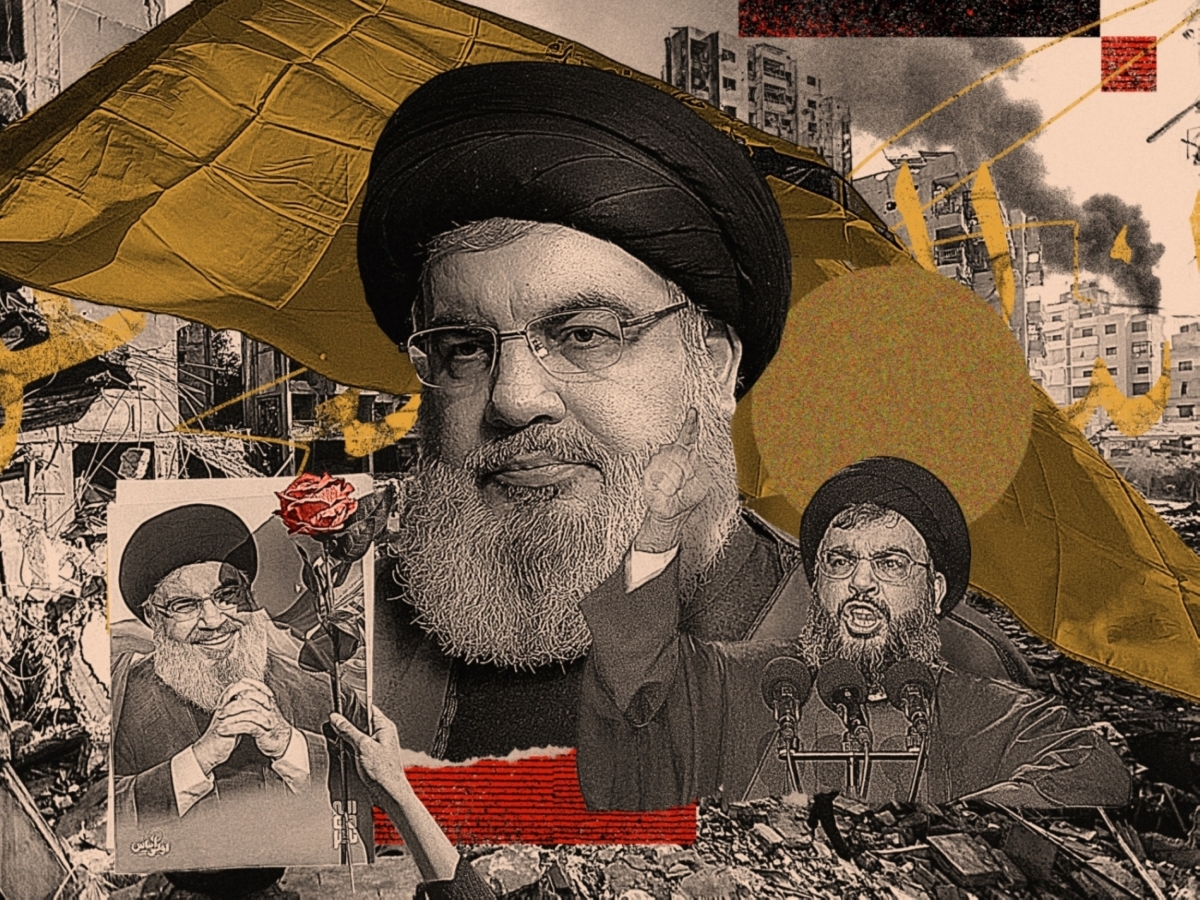

A year after Israel’s killing of Hezbollah’s leader Hassan Nasrallah on the evening of 27 September 2024, the effect on Lebanon of both his presence and his absence can be better assessed. It is a mixed legacy. Although he was closely associated with the dynamic and systematic development of Hezbollah and its broader Shiite support base, he was also linked throughout the rest of Lebanon with stagnation and obstruction.

Unlike Sayyid Musa al-Sadr, the founder of Lebanon’s modern Shiite movement, Nasrallah showed little concern for the position of Shiites within the state. His priority was instead to exert control over the state from the outside—a strategy not dissimilar to that of Chinese communist leader Mao Zedong, who envisaged the periphery (the peasantry) encircling, besieging, and toppling the urban centre (the bourgeoisie).

Whereas Nasrallah attempted to impose the will of a Shiite party on the rest of Lebanon, al-Sadr both sought to draw the state’s attention to the condition of the Shiite community and to halt the growing influence of internal left-wing forces, just as traditional feudal structures were losing their purpose in a state dominated by the Maronite–Sunni alliance in Beirut.

Gaining a foothold

For Lebanon’s Shiites, the late 1960s and 70s were marked by a lack of public services and Israeli attacks (following operations launched by Palestinian fighters based in southern Lebanon). Many Shiites in the south and the Beqaa Valley, including the educated and the young, joined leftist parties. Two big Shiite groups emerged: Amal and Hezbollah. Together, they became known as the ‘Shiite duo.’

Throughout Lebanon, problems were rife, including corruption, nepotism, and disguised unemployment. Yet what mattered to the duo was not institutional performance but securing Shiite loyalists in key state positions. This followed the path of the 1989 Taif Agreement, which effectively granted sectarian leaders the authority to appoint civil servants at all levels.

These sectarian leaders protected their interests, electoral support base, and share of state contracts awarded for infrastructure projects. As in other Arab states, loyalty was more important than competence. Nasrallah played a key role in integrating his party into the Lebanese state and its institutions, starting with his support for Hezbollah’s participation in the August 1992 parliamentary elections, just months after he assumed the position of Secretary-General.

This marked a turning point in Lebanese political life. The three powers became the Lebanese state, Syria, and Hezbollah, the latter retaining its arms under the pretext of resisting Israeli occupation. In the early years, Hezbollah said it had no interest in governance. This changed following the clashes between Hezbollah and pro-government Sunnis in May 2008. The resulting agreement (the Doha Accord) ensured a new national unity government in which the Hezbollah-led opposition would hold a third of the cabinet seats plus one, meaning in effect that it had a veto.

Building a base

Nasrallah consolidated Hezbollah’s strength over time and consistently obstructed state institutions or initiated political deadlock in order to achieve gains and expand the party’s military and civil structures. He did so with flexible allegiances. Sometimes, he collaborated with allies from the Aounist movement. At other times, he relied solely on Parliamentary Speaker Nabih Berri and the Amal Movement.