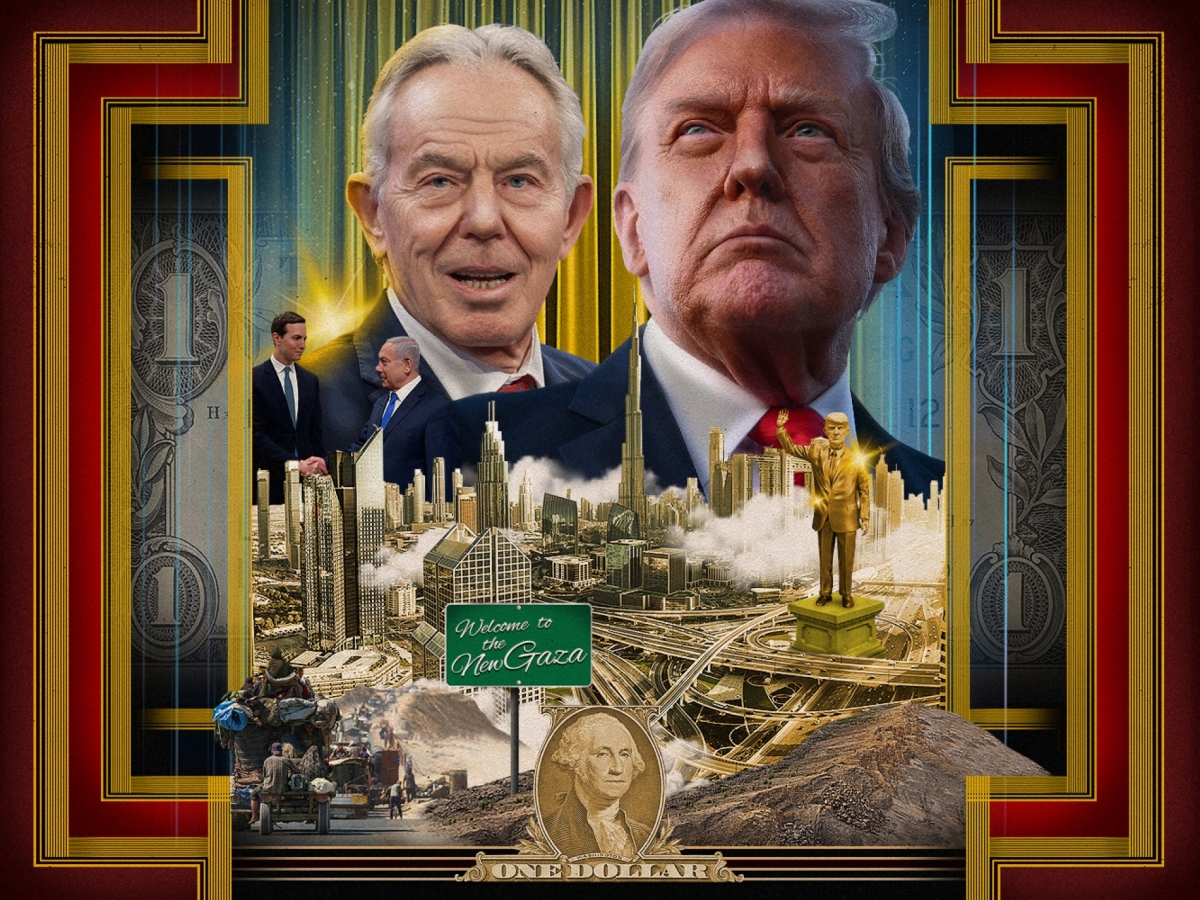

He’s back. That might be one reaction to the news that former UK Prime Minister Tony Blair is slated to play an important role in the proposed governing structure of Gaza, should the peace plan unveiled at the White House on September 29 go ahead. However, his name has been circulating as far back as February of last year, to play a role in Gaza's 'day after', which Trump and other American and Israeli officials want to turn into "the Riviera of the Middle East", akin to the glitz and glitter associated with Dubai.

Long a controversial figure—particularly in his home country—he is undoubtedly a highly successful politician. He helped turn around the fortunes of the Labour Party that had been regularly trounced in British elections across much of the 20th century. Rebranding itself as New Labour, Blair led the party to a major electoral victory in 1997 and then became only the second Labour Prime Minister ever to win a consecutive majority (the first being Harold Wilson in the 1960s) and then moved into unprecedented territory for Labour by capturing a third consecutive majority government. Even his political opponents expressed admiration: leading Conservatives David Cameron and George Osborne privately referred to Blair as “the Master” and vowed to mirror his governing style when they achieved power.

Blair’s triple electoral victory, however, masked the decline of his political star. Despite parliamentary majority after parliamentary majority, Labour’s popular vote conveyed a different story, declining from 43% in 1997 to 41% in 2001 to 35% in 2005. The last figure was the lowest ever popular vote attained by a party winning a majority government in UK history. By 2007, Blair was finished politically, having stepped down in favour of his Chancellor of the Exchequer, Gordon Brown.

The decline of Blair the politician had arguably less to do with domestic policy in Great Britain than with his policy interventions elsewhere in the world. And it is here that both a mixed record and controversy have dogged his reputation in the nearly two decades since he finished his political career.

Good Friday role

Blair’s legacy undeniably included successes. The Good Friday Agreement is a prime example. Signed on 10 April 1998, less than 12 months after taking office, the agreement—later ratified in a popular vote—ended almost all the violence associated with “The Troubles"—the decades of sectarian violence in Northern Ireland between elements within the Protestant and Catholic communities.

Although Blair received considerable acclaim for the 1998 achievement, the true picture was more complicated. Substantive talks between the Irish Republican Army and the British state had begun in the early 1990s during the Conservative government of Prime Minister John Major, Blair’s predecessor at Number 10 Downing Street.

A key driver in the Blair government towards an agreement was not the Prime Minister, but rather his Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, Mo Mowlam, who helped shepherd the main opponents through the talks, taking political risks in the process. Another important figure behind the scenes was Jonathan Powell, Blair’s Chief of Staff. Nevertheless, Blair became the face of success in Northern Ireland, burnishing his reputation as a fixer of intractable disputes.

The face of interventionism

Blair soon became the face of “liberal interventionism"— a foreign policy approach in which liberal democracies pursue military intervention in other countries. Following the Cold War—and in the immediate aftermath of NATO's military involvement in Kosovo in the former Yugoslavia—Blair envisioned a new international reality during a period of growing economic interdependence through globalisation.

He defined that view on 24 April 1999, in an important speech in Chicago entitled “Doctrine of the International Community.” “The most pressing foreign policy problem we face is to identify the circumstances in which we should get actively involved in other people’s conflicts,” he told his audience.

“Non-interference has long been considered an important principle of international order. And it is not one we would want to jettison too readily,” he added with a note of caution. He proceeded to list “five major considerations” to guide whether liberal-democratic states should intervene elsewhere:

"First, are we sure of our case? War is an imperfect instrument for righting humanitarian distress, but armed force is sometimes the only means of dealing with dictators. Second, have we exhausted all diplomatic options? We should always give peace every chance, as we have in the case of Kosovo.

Third, on the basis of a practical assessment of the situation, are there military operations we can sensibly and prudently undertake? Fourth, are we prepared for the long term? In the past, we talked too much about exit strategies. But having made a commitment, we cannot simply walk away once the fight is over; better to stay with moderate numbers of troops than return for repeat performances with large numbers. And finally, are national interests involved? The mass expulsion of ethnic Albanians from Kosovo demanded the notice of the rest of the world. But it does make a difference that this is taking place in such a combustible part of Europe."

Blair would soon pursue these principles further afield with decidedly mixed results. First came a unilateral British military intervention in the West African country of Sierra Leone—a former British colony. In May 2000, British soldiers were deployed and, over subsequent months, helped stabilise the country that had been spiralling towards a bloody civil war.

If Sierra Leone demonstrated the potential of military force to bring about political stability, the next major British armed interventions would have starkly different outcomes. On September 11, 2001, 67 Britons were among the nearly 3,000 people who lost their lives when the World Trade Centre towers were attacked by Al-Qaeda.

Blair quickly cast his lot in with the conservative administration of President George W. Bush and deemed it necessary to respond to the attack. On the one hand, Blair and Bush seemed strange bedfellows given their different ideological beliefs, but on the other, both shared a strong Christian faith and a confidence in the use of military power as a tool of foreign policy; those convictions connected Blair’s liberal interventionism with Bush’s neoconservatism.

Afghanistan, home to Al-Qaeda, came first in the Bush-Blair response to 9/11. The Taliban government was quickly toppled, and remnants of al-Qaeda, along with its leadership, fled to Pakistan. The apparent ease of the result in Afghanistan—which turned out to be illusory— fuelled hubris among American and British officials and led to a major miscalculation: the 2003 invasion of Iraq to end the regime of Saddam Hussein.

Iraq debacle

Determined to stay close to the Bush administration as a tool of influence, Blair’s decision to invade Iraq proved a major political and strategic miscalculation, which contributed to his political decline at home. The warning signs were evident even before British troops entered Iraq in March 2003.

The largest demonstration in British history took place in February 2003, when over a million people in London marched against the proposed invasion of Iraq. Behind the scenes, the British domestic security agency, MI5, warned the Blair government that invading Iraq would greatly increase the chances of a terrorist attack in the UK; this warning proved prophetic when 52 people were killed on the London transportation system by suicide bombers linked to Al-Qaeda in July 2005.

The disastrous invasion of Iraq, which descended into a sectarian civil war and led to hundreds of thousands of civilian deaths, came to define Blair’s legacy. He was accused by some of being a war criminal, and—once out of office—he found himself hounded at times, including at least five occasions when ordinary citizens attempted to arrest him.

Blair, however, was far from finished as a political influencer. Immediately upon his resignation in 2007, he became, at the behest of President Bush, a Middle East envoy for the “Quartet”: Russia, the US, the United Nations, and the European Union. His focus was on Palestinian-Israeli relations, although he had little to show for the eight years he served in the position.

While working in the envoy role, he established Tony Blair Associates in 2008. Essentially a lobbying firm, it garnered considerable work in the Middle East and Central Asia. It also led to suggestions that Blair had a conflict of interest between his envoy work and his lobbying, especially as his lobbying involved contracts with countries with poor human rights records.