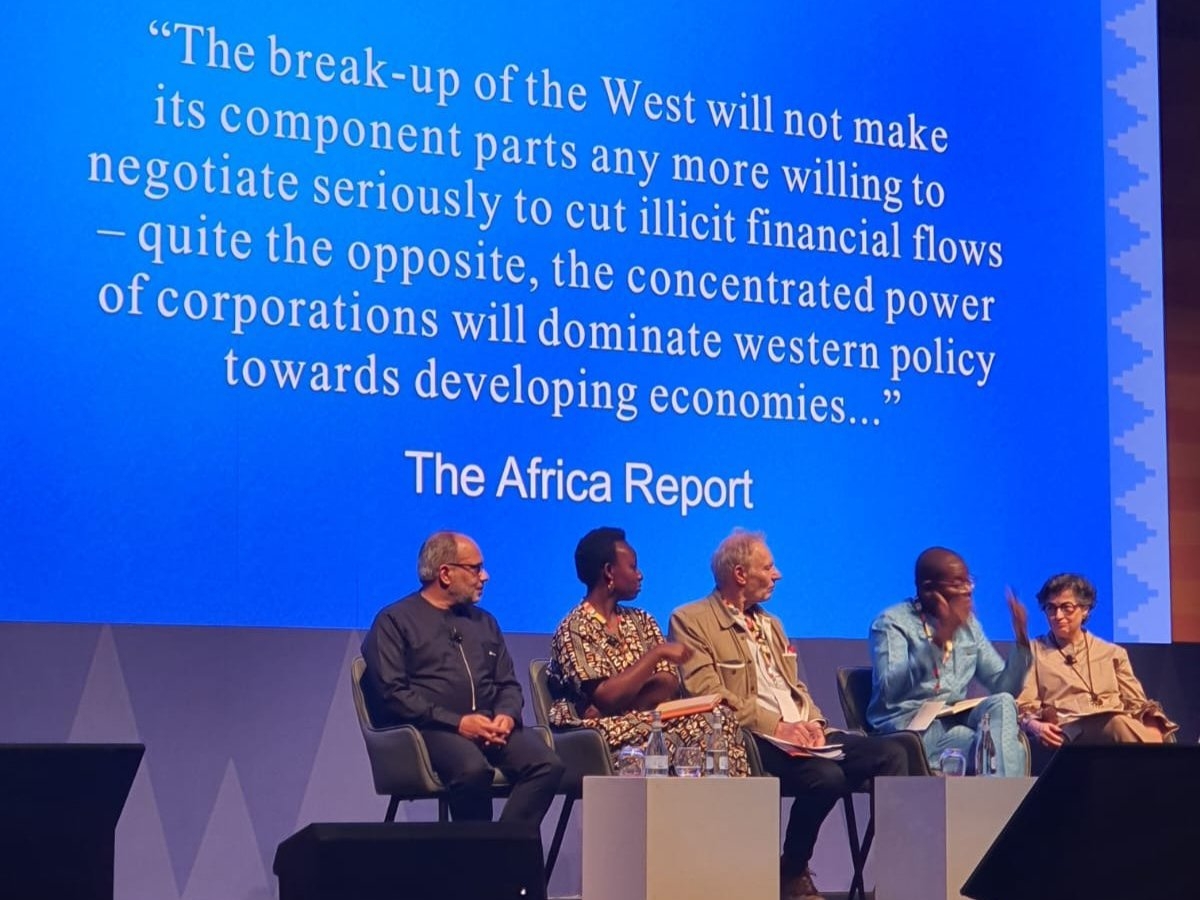

In June, Sudanese-British billionaire Mo Ibrahim—patron and organiser of the annual Ibrahim Governance Weekend which was held this year in Marrakesh, Morocco—sparked controversy after he criticised the African Union’s heavy reliance on foreign contributions, which make up 70% of the AU budget.

In a panel discussion with the chair of the bloc’s commission, Moussa Faki Mahamat, he said: “You call them colonisers, but when they give us money, they’re partners... This is a farce."

Although the remarks may appear to champion African sovereignty, they obscure a fundamental fallacy in assessing such financial contributions. Rather than being seen as charitable donations from the West—albeit framed as developmental partnerships—these funds could rightly be viewed as reparations owed for centuries of systemic colonial exploitation of the continent.

Centuries-long subjugation

Africa’s subjugation by European colonial powers began as early as 1415, with Portugal’s seizure of the Moroccan city of Ceuta. This marked the start of a ruthless wave of exploitation that culminated in the infamous “Scramble for Africa” of the 19th century. The 1884-85 Berlin Conference formalised the continent’s partition among European powers with complete disregard for its people, cultural systems, or existing social and ethnic structures.

Although Africa had been home for millennia to indigenous civilisations, rich cultures, sophisticated social systems, and complex histories shaped through interactions with neighbouring ancient civilisations, Europeans arrogantly framed their exploits on the continent as “discovering Africa”.

This long-term project, which continued into the latter half of the 20th century, left deep scars and entrenched economic dysfunctions that still plague the continent today.

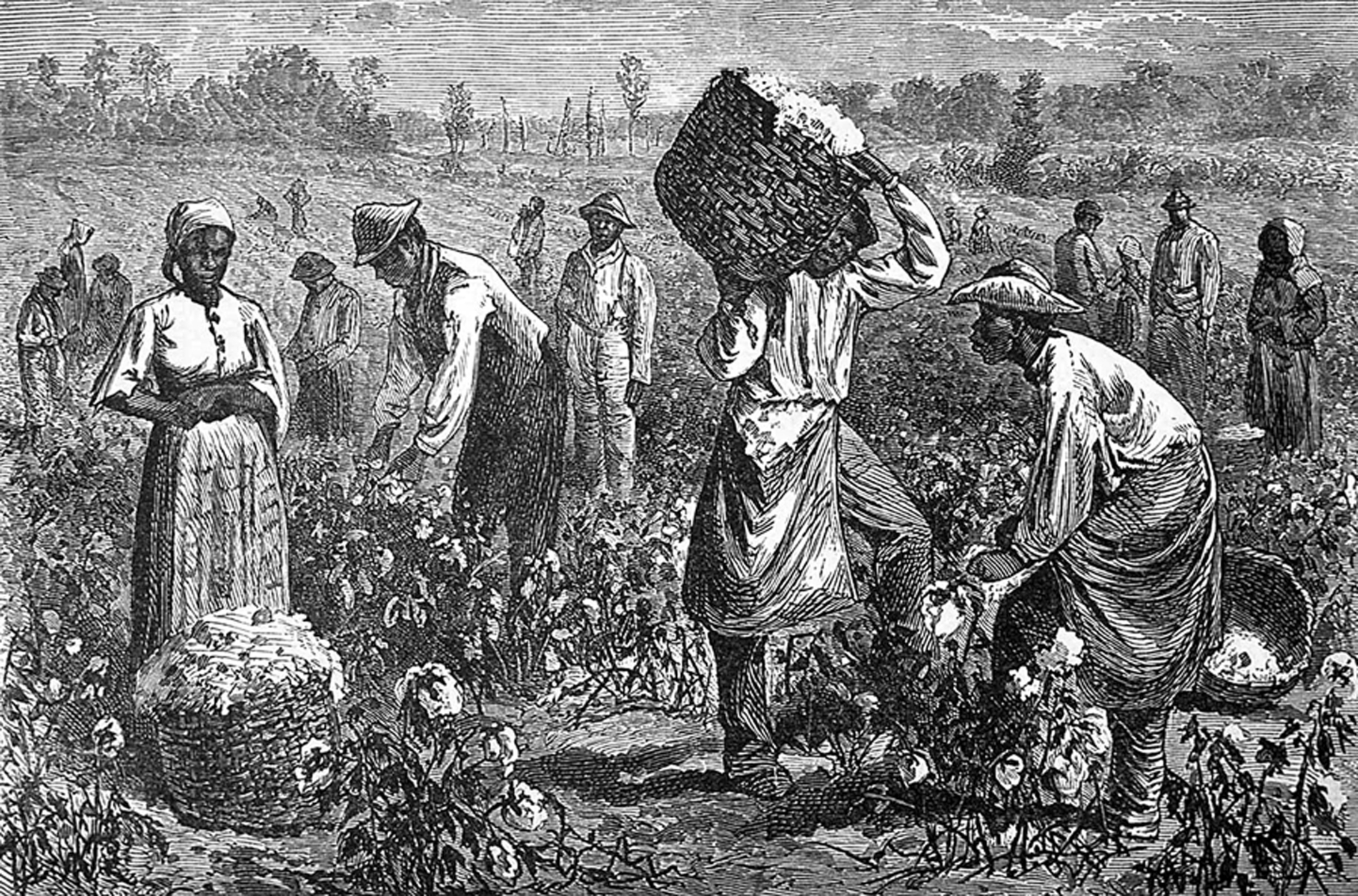

Between the 15th and 19th centuries, more than 12.5 million Africans were forcibly enslaved and transported to the Americas between 1501 and 1866. The transatlantic slave trade—one of the most egregious manifestations of Western colonialism—wasn’t merely an economic enterprise. It was underpinned by a tightly constructed intellectual framework that sought to justify the subjugation of Africans by classifying them as inherently inferior and reinforcing the ideology of white supremacy.

Lasting marks

These concepts became embedded within the modern global system, infiltrating international relations, economic structures, politics, and culture, leaving legacies that endure to this day. These were not isolated historical events, but deliberate, institutionalised processes that gave rise to modern-day racism as both an ideology and a structural reality. The colonial project relied on these notions not only to legitimise human trafficking but also to entrench a global hierarchy in which Africa was positioned at the bottom.

During the colonial era, Africa was looted on a staggering scale. Conservative estimates suggest that the British Empire alone extracted over £35tn (in today’s money) from its colonies around the world. This came in addition to a vast supply of free or nearly-free labour and immense quantities of raw commodities such as rubber, sugar, and oil.

The outflow of African wealth has persisted well beyond the formal end of colonial rule. A recent study revealed that between 1970 and 2010, sub-Saharan Africa lost approximately $814bn (at 2010 exchange rates) through capital flight, illicit financial flows, mispricing of resources, and coerced debt repayments.

That figure far exceeds the total combined value of official development assistance and foreign direct investment received during the same period—a stark indicator of the enduring dynamics of exploitation.

Beyond direct financial losses, colonialism also inflicted immeasurable developmental setbacks. By 1914, Europe’s overseas assets were equivalent to 70% of the size of its economy as measured by gross domestic product, while Africa’s colonial-era growth never surpassed 0.9%.